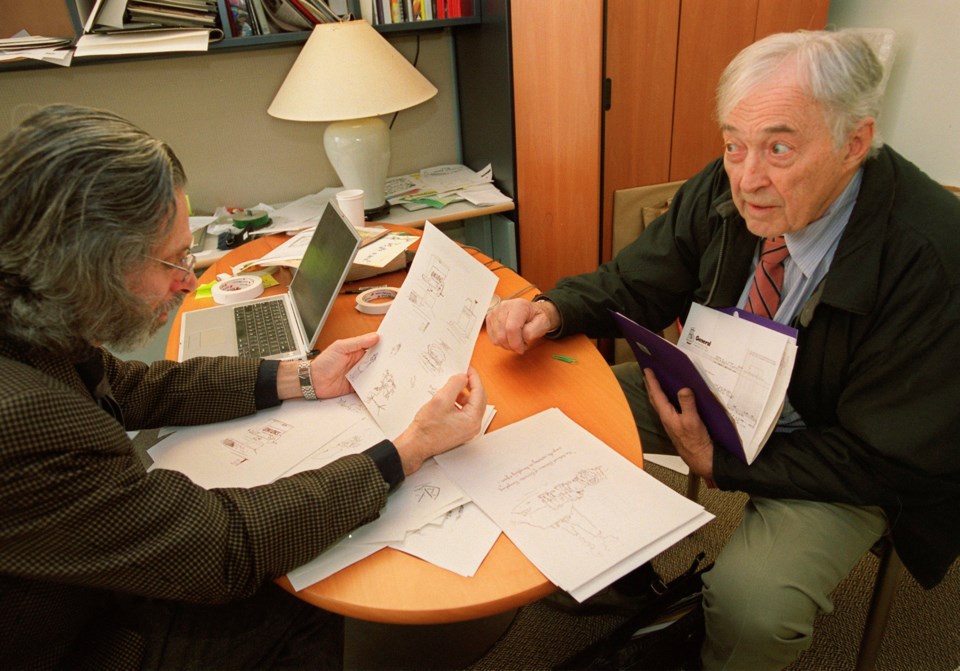

NEW YORK (AP) — George Booth, a prize-winning cartoonist for The New Yorker who with manic affection captured the timeless comedy of dogs and cats and the human beings somehow in charge of their well being, has died. He was 96.

A New Yorker spokesperson announced that Booth died Tuesday in New York City. The cause was complications from dementia.

“George Booth was a remarkable artist who sold his first drawing to The New Yorker in 1969 and filled the magazine with a kind of wild delight for decades thereafter," New Yorker editor David Remnick said in a statement. "Through his countless drawings and covers, he created an astonishing world, one that was wholly his own: chaotic, strange, beyond hilarious.”

Booth's pen-and-ink sketches often depicted farcical domestic settings, such as a dog deliriously rolling on a kitchen floor and a frazzled looking husband and wife at a table nearby. The caption reads: “Don't give the dog any more coffee.” Booth also uses a couple at the kitchen table, with a cat perched between them, for a sprawling portrait that throws in a rowboat, various buckets and tools and a chair hanging from the wall. The man is explaining to his downcast spouse: “The way I see it, Wendy, you only go around once.”

Among his most popular images was a scowling, squatting bull terrier, with a lawn sign nearby reading “BEWARE! Skittish Dog!”

Booth's work was compiled into several books, among them “Think Good Thoughts About a Pussycat” and “About Dogs.” He also completed children's stories, drew greeting cards and advertisements and designed a poster for the film “Ed and His Dead Mother.” A documentary about Booth, “Drawing Life,” was released early in 2022.

His honors included a lifetime achievement award from the National Cartoonists Society.

Booth, a native of Cainsville, Missouri, drew his first cartoon at age 3 and later was influenced by the slapstick comedy of the Marx Brothers and Laurel and Hardy among others. He was drafted into the U.S. Marine Corps during World War II and eventually became a cartoonist for the Marine magazine Leatherneck. Before starting at The New Yorker, he sold his work to Collier's and Look and for eight years served as art director for Bill Communications Inc.

Booth died less than a week after the death of his wife, Dione, whom he married in 1958. They are survived by their daughter, Sarah Booth.

The Associated Press