Britain’s colonial legacy conflicts me.

With King Charles’ coronation, as when Queen Elizabeth II passed away, I find myself pulled into discussions about colonialism. One friend jokingly calls me “white-adjacent,” for which the clearest definition I found is “a person of colour who conforms to whiteness.”

Like many people until recently, I remained largely oblivious of the enduring negative impacts of colonialism. The Twitter collective stipulates that I am expected to espouse certain views. To an extent, I do.

As a youngster, I held animosity towards Britain enriching itself through cruelty and deprivation of nations. As I matured, I came to realize that because of the British Raj, I was born in Canada instead of rural India.

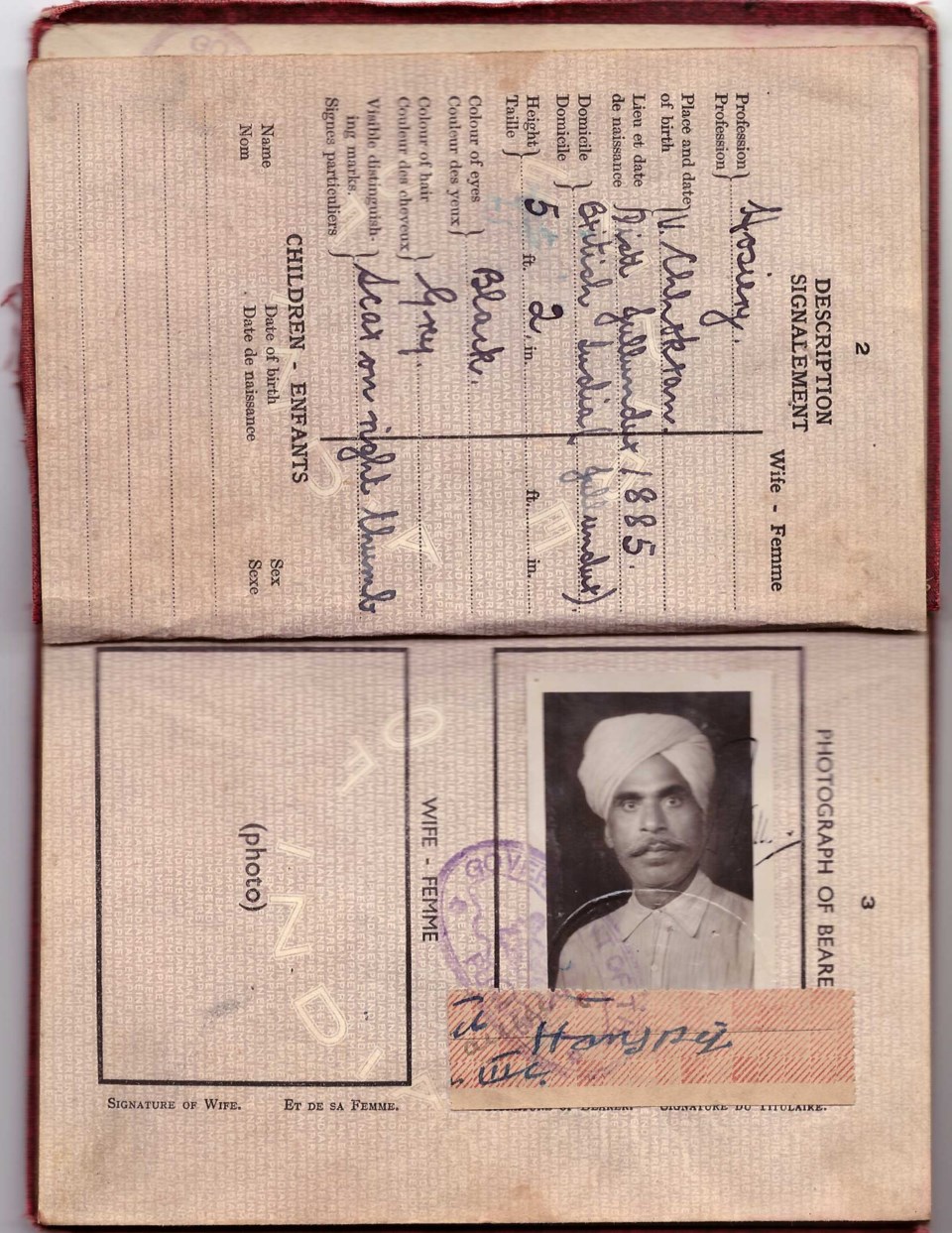

My maternal grandfather, Hansraj Sharma, was born in British India in 1885 in the province of Punjab. A subject of the colony, his British Indian passport confirms he arrived by ship in Â鶹´«Ã½Ó³»in 1930 via Hong Kong, San Francisco, and Seattle.

Not many Indians immigrated during that time due to Canada’s “continuous journey” regulation enacted in 1908 to restrict such transports, even though India and Canada were part of the British Empire. The colour of my grandfather’s passport suggests he travelled as a diplomat, something that I am exploring.

“Hindoos,” as Canadians called them, settled in several areas, particularly in lumbermill communities. Nobody is sure in which community my grandfather settled, and we can only assume he also worked in a mill.

My grandfather made the arduous voyage back to India a few times where he had left his wife. He would have three children in the 1940s – two sons and a daughter (my mother), all of whom would automatically receive Canadian citizenship due to my grandfather being a naturalized citizen.

He would renew his British Indian passport twice before he died in 1958 in India, by then an independent nation. My mother was 12.

In November 1963, her two brothers – one a young adult and the other still a teen – followed in their father’s footsteps. They flew through Montreal to Vancouver, ultimately settling in Williams Lake and working as loggers.

By the time my parents married and headed for Canada in 1967, one brother was temporarily in England and the other still in B.C. Then tragedy struck. Five weeks before my parents were to join him in Williams Lake, he and two fellow Indians died when their rented shack caught fire across from P+T Mill where they worked. He was 22.

On June 28, 1967, the Williams Lake Tribune’s front page read: “Three Perish in Shack Fire: Bodies Recovered after Long Battle.” Their deaths became the subject of a coroner’s inquest.

About 20 years ago, the Williams Lake fire chief at that time, Dale Moon, sent me all public documents related to the fire. He was a junior on the scene that night and said he remembered it well.

The details exude pain. The coroner’s report concluded my uncle died due to “shock and asphyxia associated with extensive burns,” and that the condition of his body – “charred and cooked” – made it impossible to get a blood sample. Faulty electrical wiring caused the fire and caused another one earlier that year. The landlord ignored maintenance.

Black and white photos reveal my parents’ grief as they left India. And the fire changed their course from Williams Lake to Â鶹´«Ã½Ó³»where they landed on August 1, 1967. They had seven dollars.

Learning English became their priority to integrate and become contributing citizens. Elderly white neighbours were among their first friends, helping them navigate a new world while learning about my parent’s Indian traditions. And as I understand, they loved my Mom’s cooking.

Diversity and inclusion were genuine in their neighbourhoods on Vancouver’s Dumfries Street and Ontario Street, and Richmond’s No. 6 Road.

Dad worked in lumber mills. Mom made a home for our growing family. The only language we were allowed to speak at home was Punjabi, lest we lose our mother tongue.

Several times, we went to India to remain connected to our heritage. Britain’s enduring legacies always struck me: transportation networks (roads, railways, ports), the parliamentary system, justice systems, universities, tea, cricket, and the English language.

And the Brits also left many atrocious legacies, including the parting shot that created a deep divide between Hindus and Muslims: the partition of British India in 1947 into two dominions, India and Pakistan. I recall a documentary calling it, “The largest and deadliest migration in human history,” as Hindus, Muslims and Sikhs left their homes to settle in lands divided along religious lines.

This refugee crisis of monumental portions signalled the end of an empire and the start of a post-colonial era rife with religious wars that continue today.

In recent years, a global cultural shift rightly focused our collective consciousness on the ugly side of imperialism. And with all the attention these past few months on the late queen and new king, people are again reflecting on and questioning the monarchy’s relevance.

I feel sentimental. My parents struggled plenty in Canada, like when my Mom’s first childbirth became an emergency Caesarean section that hospitalized her for 10 days. Dad needed $10 for the hospital bed rental, plus $2 for the taxi home ... to say nothing of baby formula, grocery, and rent. When he asked his employer for his daily $5 earnings – and even explained why he needed the money – his employer refused to pay the full sum.

Then there was the sheer number of times through the 1970s and early ‘80s people told us to go back where we came from. Some interactions ended in fisticuffs, many in tears, and all in confusion. After all, my grandfather, uncles, and Dad worked hard and paid taxes. My sisters and I were born here. Where did these people want us to go?

One episode ended with my Dad being criminally charged, all for defending his young family. Thankfully, he was acquitted in large part to a young lawyer named Wally Oppal who became one of Canada’s most accomplished South Asians – a B.C. Supreme and Appeals Court Justice and attorney general.

Through adversity, my parents endured. And thanks to them – as poor as we were – we breathed clean air, eventually had heat in the winter, and received opportunities for education and careers.

My parents taught us the value of hard work and appreciation for this great country. They even put a Canadian flag outside our home, which remains today. And though we only became a modest working-class family, my parents contributed meaningfully to the less fortunate, even when they had nothing, earning my dad an Order of BC in 2007, and then in 2012, a Queen Elizabeth II Diamond Jubilee Medal.

My mother and her immediate family are now deceased. Sadly, she and her brothers died young, but each left a legacy of great respect among their extended family and South Asian community.

I hold them in reverence. Through hardship, the Sharma family created opportunities for their descendants. They, along with my parents, also opened doors for my father’s vast family, now four generations deep in Canada. It was all made possible by an intrepid man – only five feet, two inches tall.

While many legacies of the British Empire – and lack of reparations for its injustices – disturb me, I still feel pride in that British Indian passport.

Renu Bakshi is a former long-time journalist who now works as an international crisis manager and media trainer. She is based in Â鶹´«Ã½Ó³»and can be reached at [email protected].