B.C. manufacturers’ supply chains are more reliable than they were during the COVID-19 pandemic, which created product shortages and sent shipping rates soaring.

That reliability could change if the 9,300 rail workers at Canadian National Railway Co. (TSX:CNR) and Canadian Pacific Kansas City Ltd. are unable to reach new labour agreements, given that those .

“Supply chains are improving but they are very fragile,” BC Food & Beverage Association CEO James Donaldson told BIV. “Everything is so interconnected.”

Many of Donaldson’s members import six or seven ingredients to make one product, he said. If any of those imports get delayed, production could grind to a halt.

For many corporate executives, however, the biggest change related to their supply chains this month is that they need to comply with added government scrutiny.

A wide swath of manufacturers must report to government on what they are doing to ensure their supply chains contain no child labour.

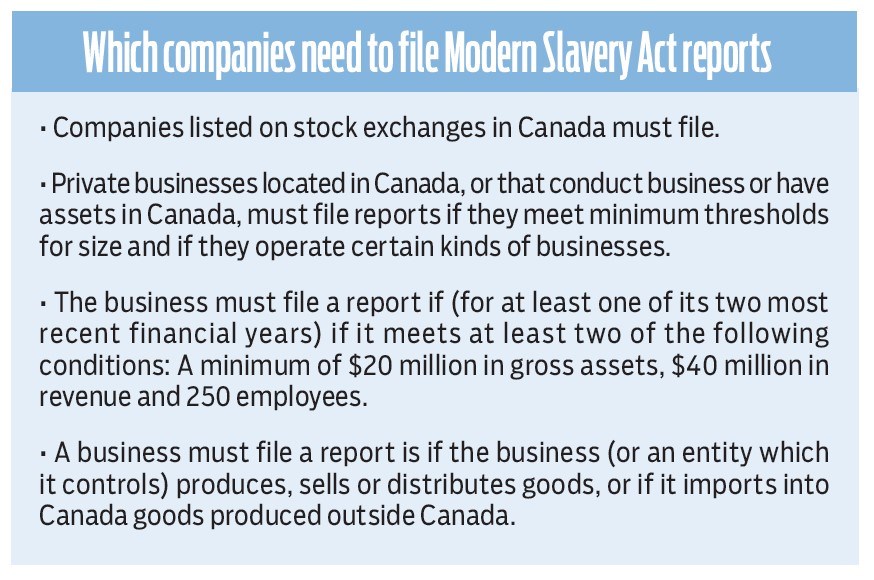

The Canadian government’s Fighting Against Forced Labour and Child Labour in Supply Chains Act (often called the Modern Slavery Act) took effect Jan. 1. It mandates that all public companies and many large private businesses file such reports with Public Safety Canada by May 31.

“As a standalone, it’s not that big a deal, but it just becomes one more thing that a company has to deal with,” Donaldson said.

Some executives told BIV that the new reporting requirement is like filing taxes: Something that uses resources and has no benefit for business operations.

Others are taking the new legislation in stride, saying it does not take much staff time and that it gives companies the ability to highlight how much they have always done to ensure child labour is not used to create their products.

“Our report is five pages long,” Burnaby-based Mustang Survival CEO Kenny Ballard told BIV.

He said his staff followed government instructions on how to prepare the report and completed the work early enough that the company’s report was filed with weeks to spare.

The government’s bill does not specify how deeply companies need to dig into what they are doing to ensure no child labour is being used in their supply chains, Tristan Packwood-Greaves, an associate at Norton Rose Fulbright, told BIV.

The requirement is that they simply reveal the steps they have taken.

Public Safety Canada plans to post the reports on its website.

“The reports must also be published in a prominent location on the company’s own web page,” Packwood-Greaves said.

Ballard’s company needs to file a report because the outdoor clothing, dry suit and flotation protection-equipment maker generates nearly $100 million in annual revenue—a tally that is increasing by a low double-digit percentage annually, Ballard said.

Mustang Survival has more than 350 workers worldwide, including about 210 at its Burnaby headquarters, he said.

Founded in Gastown in 1967, the venture has long had its own manufacturer’s handbook, Ballard said.

“All of our suppliers have to sign and comply to that manufacturer’s handbook, which specifically addresses the issue of modern slavery, forced labour and that type of thing, as well as employee benefits, salaries, treatment of employees, conflict resolution and a number of issues,” he said.

Ballard joined Mustang Survival in January and has yet to visit its suppliers’ factories in Asia, but he said he plans to do that this fall and that other company executives have made many such visits in the past.

Ballard added that his company’s supply chain is functioning smoothly.

It is not impacted by Houthi rebels attacking ships in the Red Sea, prompting longer shipping routes between Asia and Europe. Nor is it impacted by the drought in Panama that has reduced the number of ships that can pass through the Panama Canal.

Top executives at other large B.C. manufacturers are less keen about the government’s new requirement to document efforts to ensure there is no child labour used in their supply chains.

“It is a burden,” Purdys Chocolatier president Lawrence Eade told BIV.

“It is something new that we have to do, just like filing your taxes is a burden, but it’s also part of being part of the society.”

He said the new regulatory requirement comes on top of other government intrusions into business, such as new requirements for front-of-package labelling.

“Purdys has been focused on sustainable cocoa for well over 10 years now and was one of the first organizations to really be doing that,” he said.

“Our efforts have been around clean water, educating women and getting children to stay in school to really improve yields in the cocoa farms, and the cocoa-producing areas, so that they can they can make a better livelihood.”

Purdys has experienced higher costs and delays importing raw ingredients thanks to challenges in global shipping, Eade said. He added that these problems “pale in comparison” to supply-chain disruption during the pandemic.

The recent Rogers Sugar strike put a dent in how much sugar was available in Canada, so that forced Purdys to be creative in its sugar buying, Eade said.

Bad weather, disease and failing trees in western Africa have pushed global prices for cocoa higher, he added.

Eade estimated that cocoa prices jumped about fourfold between the end of April 2023 and late April.

Prices then started to fall earlier this month, and in mid-May were only up by about 2.5-to-three times what they were one year earlier, he added.

“We’re going to have to pass some of that cost on to customers,” he said.

Smaller manufacturers face challenges

Smaller privately owned manufacturers do not need to worry about Ottawa’s new forced labour reporting requirements.

Some of them, however, have been whipsawed with multiple supply-chain challenges in recent years.

“In the past six months it has gotten better,” Big Mountain Foods principal Jasmine Byrne told BIV. “After COVID, we had a drought, a war and the floods in the Fraser Valley.”

The 13-day strike at the Port of Â鶹´«Ã½Ó³»last summer did not help. Byrne said some product shipments were stuck in containers.

She is happy to be in a period of relative calm.

During the pandemic, her 52-employee company—which produces plant-based foods—had trouble acquiring packaging film and plastic packaging, which was rapidly rising in price. She responded by placing a large order because she said feared that she would not get the packaging when needed. Prices for the packaging then normalized but Byrne was on the hook for the higher-priced packaging.

The drought Byrne mentioned affected the Canadian prairies in 2020 and 2021, and limited farmers’ chickpea production, she said.

“You buy your crop a year later,” she said. “Sometimes farmers will sit on the crop for 18 months. The price skyrocketed and they were selling it to whoever would pay the highest price. A lot of the chickpeas were not even staying in Canada. It was going overseas.”

Russia’s war in Ukraine doubled the price of imported sunflower oil, prompting Byrne to buy sunflower oil from an Ontario farmer that charged more than the pre-war price, but less than European producers, she said.

Other recent supply-chain glitches came in fall 2021, when flooding paralyzed the Fraser Valley, making the transportation of some products impossible.

Byrne said she worries that forcing companies to produce Modern Slavery Act reports will simply add to the regulatory burden that makes doing business in Canada more expensive.

“From an ethical standpoint it makes sense,” she said.