Last Sunday, nearly 60 runners met in Stanley Park to run one or five historical loops along the Seawall and under the trees.

They were marking the 45th anniversary of the Ā鶹“«Ć½Ó³»marathon. The BMO-sponsored marathon and half-marathon starts near Queen Elizabeth Park Sunday, May 1.

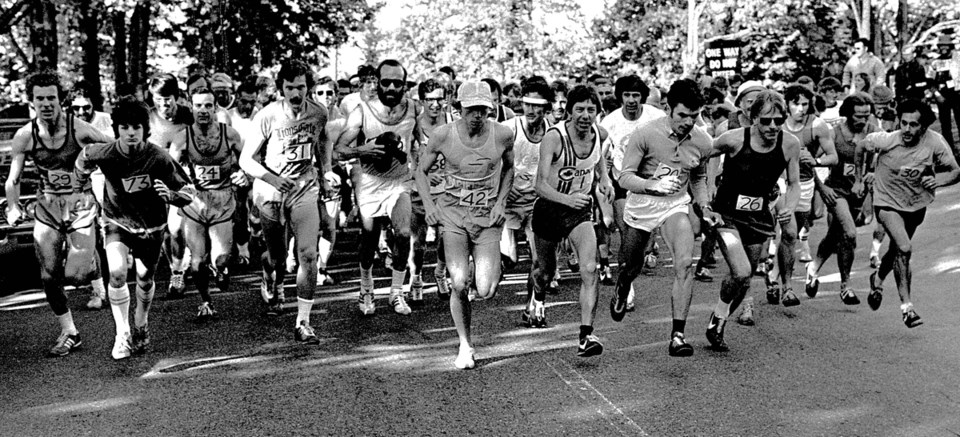

Those who ran last Sunday followed in the footsteps of the 32 finishers who competed in the inaugural Ā鶹“«Ć½Ó³»International Marathon organized by the Lions Gate Road Runners in 1972. Others were drawn to the park simply to cheer them on.

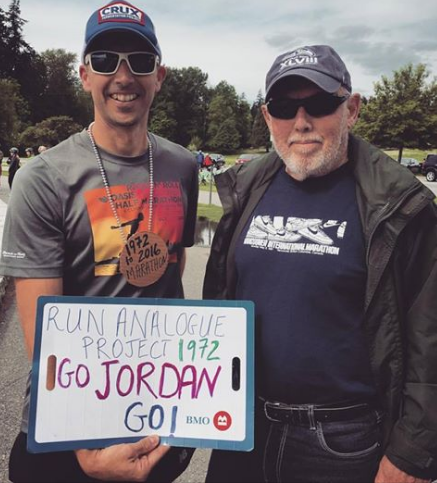

On the 45th anniversary of the fringe event many once considered an extreme sport, Jordan Myers, a former race director with the BMO Ā鶹“«Ć½Ó³»Marathon, imagined the low-budget, high-endorphin Run Analogue Project and invited runners to tackle a self-supported marathon (or just as many laps as they wanted) in Stanley Park just as they did in 1972.

From that start, Ā鶹“«Ć½Ó³»now hosts the oldest continual marathon in Canada. Itās also one of the biggest.

Since that race four decades ago, here are a few ways the Ā鶹“«Ć½Ó³»marathon has changed:

Ģż

Changing course

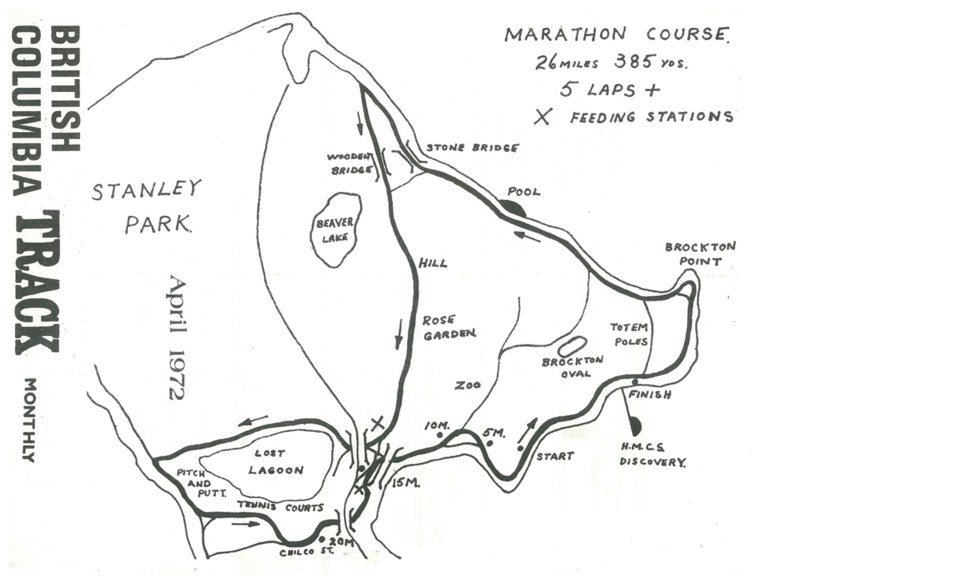

In 1972, racers made five laps of the same course through Stanley Park.

That lasted for four years before the marathon branched out to city streets. In the ā90s, a far-flung course led racers over the Lions Gate Bridge and back across Second Narrows Crossing, where they shared the Trans Canada with highway traffic.

Don Basham, who was the race director for 16 years starting in ā72, dealt exclusively with the park board until 1976 when the course expanded to downtown.

āI was the first one to ask for permission to have any road race on a road,ā he said this week.

Now the marathon sees the cityās largest deployment of police offices and, between the marathon and half-marathon, covers more than 70 kilometres of pavement, including streets and the Seawall.

Ģż

Empire struck down

The course was 26.2 miles. Itās now 42.1 kilometres.

Ģż

Cut off

The dedicated athletes who ran the marathon in the ā70s were not weekend warriors. They were elite, semi-pro and national competitors who ran sub-four-hour marathons on training days. Unlike todayās seven-hour limit, the race did not have a cut-off time.

āWe never had runners who were that slow,ā said Basham, himself a sprinter who competed against world record holder, North Vancouverās Harry Jerome.

The first time limit was introduced when the race moved out of the park. It was four hours.

Ģż

Recreational expectationsĢż

Nearly half a century ago, racers ran a self-supported distance. There were no aid stations with water, gels or bananas. No portable toilets.Ģż

With more non-competitive running clubs and friend groups, a growing number of people sign up to completing a bucket-list challenge.

āThe balance has tipped the other way,ā said Basham. āIn the ā70s weād have more than 80 per cent serious runners who belonged to running clubs and were out there for the time as opposed to people who just want to see if they can finish.

Today, those racers have more demands and the international elite have specific needs, too. Said Myers, who now helps organize the Lululemon Sea Wheeze, āThere is a lot more professionalism. The expectations of participants are very high.ā

Ģż

Ģż

Money talks

Through the years, the cityās only marathon was sponsored by Labattās, Bud Lite, Adidas, Asics and Nike.

Ģż

Always referred to as the VIM, for Ā鶹“«Ć½Ó³»International Marathon, the āinternationalā was dropped after almost 40 years, and in 2009 the race became generally known as the BMO for the titular sponsor.

In Canada, many races are also known as banks, including several Scotiabank and province.

Ģż

Cost of inflation

In 1972, racers paid $1 to run five loops around Stanley Park.Ģż

The full price to register for the BMO Ā鶹“«Ć½Ó³»Marathon this year was $149. Cost to walk up and register during the Expo is $159.Ģż

The full cost of the half-marathon is $119.

Ģż

AI: Asphalt Intelligence

With barely three dozen racers on the course, officials kept hand-written paper records of times and distances. At the finish line, a stop-watch kept pace and the time was shouted out loud and recorded on a clipboard. Cheating might have been easy, but it wasnāt the nature of these early racers, said Basham.

āWe hardly ran into challenges like that.ā

This Sundayās marathon will count 5,000 racers wearing tiny chips on their shoelaces that record their time at intervals along the course.

Ģż

Squad goals

Not immune to societyās predominant sexism, many marathons banned women from competing. The Ā鶹“«Ć½Ó³»International Marathon rose above the prejudice its first year by registering, officiating and timing female racers as equal participants to the men.

How things have changed. āIn a lot of races now, there are more women than men,ā said Basham.

In 2015, for example, 4,574 women completed the half-marathon compared to 3,275 men.