Here’s what John Horgan and Andrew Wilkinson should talk about in Thursday’s televised electoral-reform debate: the flaws in their own arguments.

Here’s what John Horgan and Andrew Wilkinson should talk about in Thursday’s televised electoral-reform debate: the flaws in their own arguments.

It’s not good enough for either simply to sell his own side like a shiny-on-the-outside used car. They also have to acknowledge the wonky steering, the coffee-stained seats and an odometer that reads like the price of a Yaletown condo.

No electoral system is perfect. Nor is it as bad as its opponents say. Yet so far, all we have heard from the two sides in this tug-of-war are the extremes, the best-case and worst-case scenarios.

To listen to the NDP and Greens, proportional representation would result in a political Woodstock where a multiplicity of divergent interests sit cross-legged in a circle, smoke a little weed, trade perspectives and then, having hashed out their differences and reached consensus, link arms and sing Kumbaya.

Ah, but listen to the B.C. Liberals, and pro-rep would bring nothing but instability and Machiavellian intrigue as politicians connive to acquire, then cling to power, rewarding flat-Earth fringe parties with kingmaker status and handing influence to racist crackpots.

The truth is somewhere in the middle, albeit hard to find while buried under so much hyperbole.

So, yes, it would be good to hear Liberal leader Wilkinson talk about the holes in the existing system he defends, first-past-the-post. Ditto for Horgan and the shortfalls of pro-rep.

Here’s what Wilkinson needs to address: The current system is a known quantity, simple and easy to understand, but so was the Model T. That didn’t make it a great car.

The status quo gives governments power disproportionate to their support. In 2001, the Liberals got 58 per cent of the vote but 77 of 79 seats, with only poor Joy MacPhail and Jenny Kwan left to speak for the 22 per cent of British Columbians who voted NDP.

It forces people with significant political differences to climb into bed together if they want to gain power, as members of the Progressive Conservatives and Alliance (née Reform) did in the 2003 coupling that spawned Stephen Harper’s Conservatives. Talk about that, Andrew.

Horgan has the tougher challenge, because he has two hurdles to clear.

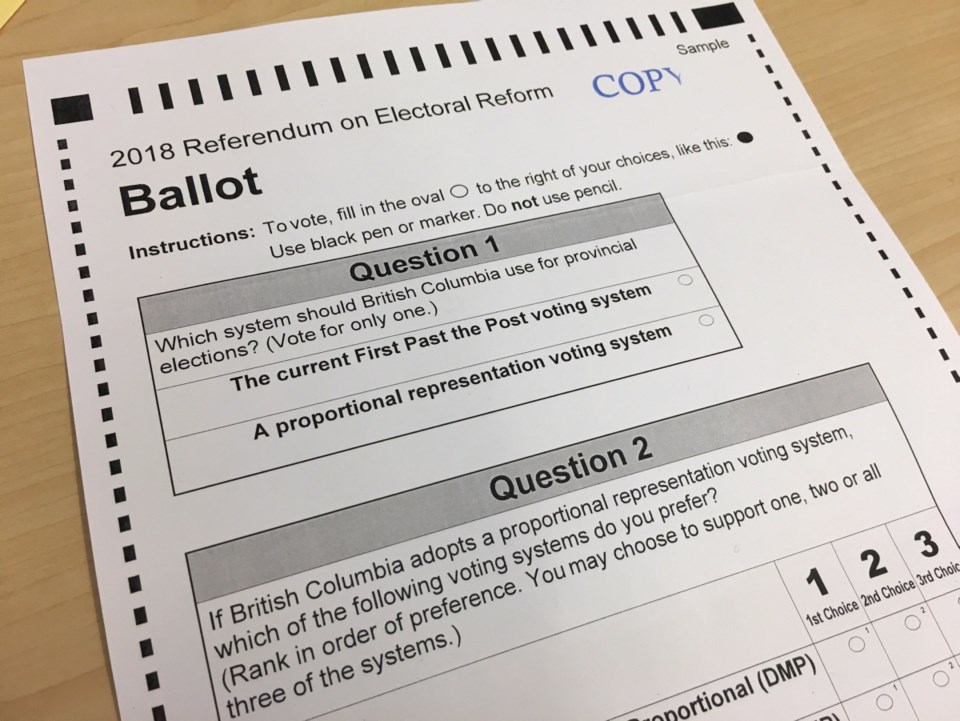

First, he must explain and make people less fearful of three pro-rep alternatives they don’t understand. If he doesn’t do so, he is effectively asking people to trust him the way they trust their car mechanic, with more lump-in-throat faith than knowledge-based confidence.

Second, he needs to make people comfortable about what kind of governments those pro-rep alternatives would produce.

The three pro-rep choices are more complex than the “40 per cent of the vote gets 40 per cent of the seats” mantra of their backers. The dual-member alternative would see voters elect two local MLAs, but good luck explaining to the typical voter how that second seat gets determined, and that it might reflect the provincial results more than the local.

Under the mixed-member option, two types of MLAs are elected: The ones you vote for directly, just as you do now, and others — about 40 per cent of the total — who are added to reflect the wider popular vote. Those second MLAs come from a list drawn up by the party, possibly with no direct input from voters. That can result in a class of MLAs who are more accountable to the party than the electorate, critics argue.

The rural-urban alternative employs two different voting systems, the idea being to address variations in population density. In the boonies, mixed-member would be used, while in the cities, existing ridings would be combined in much larger districts, with voters ranking candidates to choose multiple MLAs. Critics say not only is figuring out the winners complicated (there’s not room here to explain the single transferable vote) but we don’t yet know what counts as rural or urban.

Opponents also say that no matter which form of pro-rep is chosen, you don’t really know what platform you’re voting for, because nobody knows what kind of post-election horsetrading must be done — what sell-your-soul compromises must be made — for a coalition to be formed.

Remember that after the 2017 election, Christy Clark was so desperate to retain power that she chucked half the Liberal policy book out the window in an ultimately unsuccessful attempt to woo the Greens. Instead, the Greens cut a deal with the NDP based on eight pages worth of clearly spelled-out promises, including holding this referendum (which was already part of the New Democrat platform) at this time (which wasn’t).

This is what makes it tough for Horgan: In trying to sell us on the unfamiliar, he faces endless what-if scenarios, some of which stray into flat-out fearmongering. The questions can’t all be dismissed as such, though. Neither the premier nor Wilkinson should gloss over what’s wrong about what they think is right.

• The leaders will debate at 7 p.m. Thursday on Global and CBC television and radio.