You probably don’t want to read this if you own a car in Vancouver.

But you probably should.

In fact, there’s a very good chance you have experienced what I’m about to tell you: break-ins to vehicles in this city are completely out of control.

Between January and September of this year, the number of reported thefts from vehicles to the Â鶹´«Ă˝Ół»Police Department totalled 12,312. The quick math: that’s more than 40 break-ins per day.

Compared to the same nine-month period in 2010, that’s a 99.8 per cent increase, according to VPD statistics listed in a report that goes before the Â鶹´«Ă˝Ół»Police Board Thursday.

Let me write that again: a 99.8 per cent increase since 2010.

Before I go on, I should mention these are the “reported” statistics. If you talk to enough friends and colleagues, they’ve probably told you about a break-in that wasn’t worth reporting.

The reasons likely had something to do with paying a ridiculous insurance deductible, or simply being too busy to bother with such a nuisance crime. Either way, they were victims.

Regular readers will know the increase in break-ins to vehicles isn’t a new trend in Vancouver. Back in February, I wrote a piece noting the number of thefts from vehicles almost doubled in the last eight years, jumping from 7,266 in 2011 to 14,958 last year.

Those stats were for the entire year.

So looking at the 12,312 reported for the first nine months of this year, it’s quite likely those 14,958 break-ins in 2018 will be surpassed by the time we bid adieu to 2019.

Which is not good news at all.

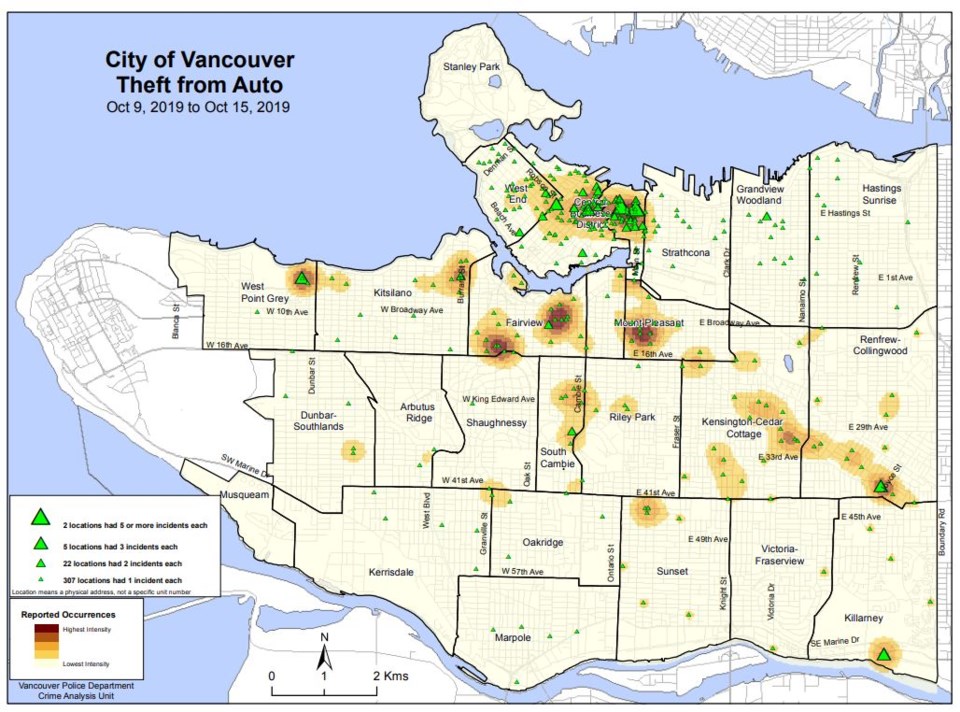

Break-ins to vehicles occur across the city, but the VPD’s most recent “crime heat maps,” which cover the period from Oct. 9 to Oct. 15, show the largest concentration of thefts occurred downtown.

So why is this type of crime on the increase?

I get the same answer every time I speak to a police officer: by and large, it’s drug users wanting to get their hands on whatever items they can from a vehicle to sell on the street for drugs.

This from an interview in 2016 with Police Chief Adam Palmer:

“A lot of these are crimes of opportunity. So people will be walking down the street trying doors, they’ll be looking in cars. If they see anything of value, if they see some loonies and toonies and quarters in your cup holder or something, they’ll break into your car to steal that.”

Palmer and his predecessor, Jim Chu, have repeatedly called for treatment on demand for drug users. Because, as Palmer said, Â鶹´«Ă˝Ół»is not a city “where if somebody is addicted to drugs and they need help and they come forward to a police officer, or just want to self-report and get help, they don’t have anywhere to go.”

Which brings me to a related topic to be discussed behind closed doors at Thursday’s police board meeting: decriminalization of drugs.

Actually, the topic listed on the in-camera agenda is “the Portugal model,” which is a reference to that country’s approach to drug addiction, where all drugs for personal use are decriminalized.

Has it led to less crime?

According to a I read, Portugal’s program led to “dramatic drops” in drug-related crime.

Insp. Bill Spearn of the VPD’s major crime unit will deliver the presentation. Spearn has appeared before, including in January 2018 when I had some Langara College journalism students grill him about the city’s opioid crisis.

Before I drop a quote in here from Spearn, it should be pointed out such a presentation shouldn’t come as a surprise to those who have followed the to drug use in this city.

The department has had a drug policy on the books for years and supported the opening in 2003 of the Insite supervised injection site. Officers also carry — and have administered — Naloxone, the overdose-reversing drug.

Palmer has repeatedly said his force does not arrest people for personal use, unless tied to another event. Officers also don’t attend overdose calls unless asked to do so from firefighters, paramedics or others concerned about safety.

The reason cops don’t attend overdose calls is because drug users’ associations and advocates lobbied for that change.

They made it clear that a person who may have an outstanding warrant — or some other matter tied to them that would land them in jail — would likely not call 911 if their buddy was overdosing, and knew the cops would show up.

Finally, here’s the big shift from the department, which doesn’t get the play that the war-on-drugs narrative continues to get: The VPD supports the program at Crosstown Clinic in the Downtown Eastside where a select number of chronic drug users are offered medical grade heroin and the legal analgesic, hydromorphone.

It’s the only clinic in North America that allows this, which, by extension makes the federal government the only government in North America to give such an experiment the green light.

To emphasize the VPD’s support of this approach, which some would argue is more radical than decriminalization, here’s that quote I promised from Spearn:

“I’d like to see a lot more treatment options available for people — a multitude of treatment options. Specifically, I’d like to see opioid replacement therapy. I’d like to see what’s occurring at the Crosstown Clinic on a much larger scale available throughout the province to people in all communities.”

Spearn will likely bring this up in his presentation and, as he has mentioned in previous public talks and interviews, will refer to the number of people who died of a drug overdose in Â鶹´«Ă˝Ół»last year.

It was 394.

As of August of this year, the death toll reached 182.

Meanwhile, somewhere in the city, another vehicle likely just had its window smashed out.

@Howellings