First, letâs get real: Nobody is going to change the name of British Columbia.

First, letâs get real: Nobody is going to change the name of British Columbia.

Good idea or bad, it isnât going to happen.

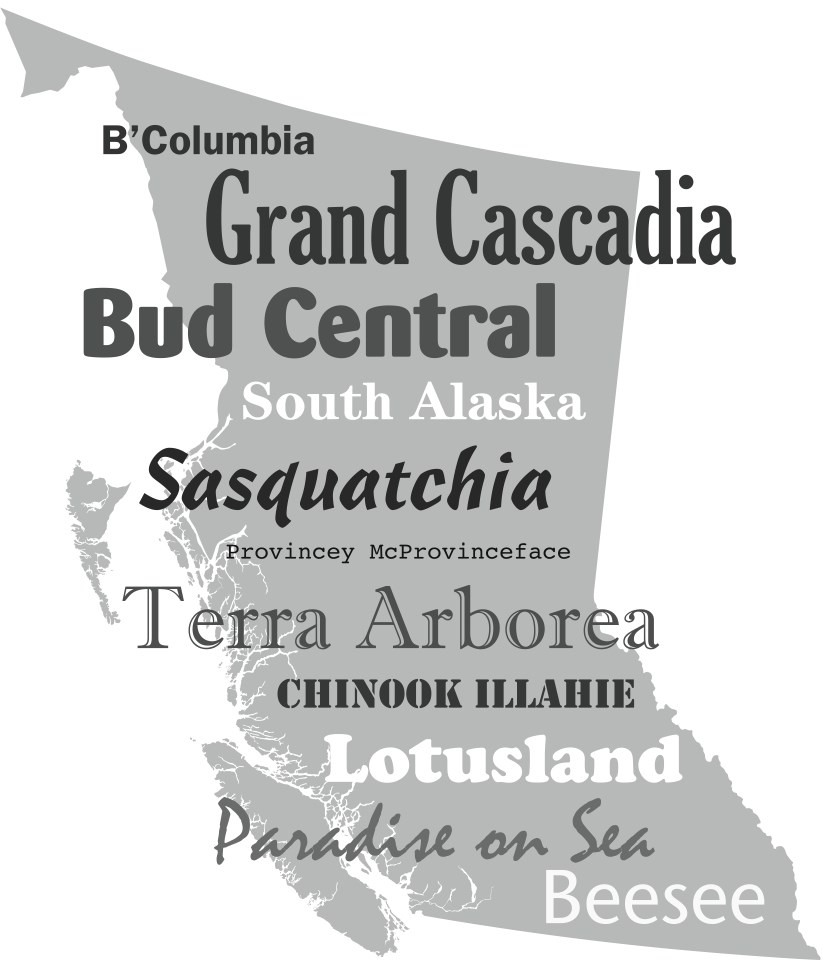

Itâs an intriguing proposal to debate, though, as proven by the response to last Sundayâs column. After we asked readers to submit alternative names, more than 300 poured in. Some were serious, some frivolous, some thoughtful, some racist, some anatomically challenging.

All were in response to an idea first advanced a decade ago by Victoriaâs Ben Pires, who argues the provinceâs current name is neither historically accurate (direct British rule didnât last that long) nor inclusive. Thinking about that perspective was the real point of the exercise.

The most popular choices for a new name? Dozens of readers favoured some variant of either Pacifica or Cascadia, though the latter is a little confusing in that the term already refers to the region from northern California to Alaska.

J.C. Scott proposed Cascadian as a specifically Canadian option. Garry Pigeon liked Nouveau Cascadia. Sadie Quintal pitched North Cascadia, as did Andrew Reding, who added that Washington state (which gets confused with D.C.) could become South Cascadia. Composer William Brookfield proposes Grand Cascadia and has written and recorded an anthem of that name.

One other hurdle: Seismologically, Cascadia is also synonymous with The Big One. âOur region would be taking the name of an unstable place where impossibly rigid geographic plates collide,â wrote Marc Christensen. âAs widely understood as the name is, it fundamentally means âearthquake land.â Fair warning: You could say thatâs our province, to a fault.â

Many respondents were eager to get away from the British part of the provinceâs name. Canadian Columbia, suggested Ivan Poitras as a replacement. BâColumbia, wrote Claude Maurice. Roy Thomas advanced New Columbia.

Maybe just go with Columbia, one word, said Bill Cann. Pacific Columbia, offered Dan Lewis of Tofino, who said he has been addressing envelopes that way for 40 years. West Columbia, said Lloyd Davies. Or Southeastern Columbia, chimed in Dolly Ahluwalia, who has either a good sense of humour or a bad atlas.

Muddying the waters, Chris Gainor forwarded a magazine article that argued the word Columbia was itself a bit of Brit-bashing. The name, derived from Christopher Columbus, became popular at the time of the American Revolution as the poetic representation of the new nation. It was a deliberate attempt to create an allegorical figure distinct from its Olde Country counterpart, Britannia.

Some readers wanted to just keep the provinceâs short form, turning British Columbia into B.C. in the same way the Bank of Montreal became BMO and Kentucky Fried Chicken morphed into KFC. Still others favoured a phonetic alternative: Beesi (Meghan Porter), Beesee (Bernard von Schulmann), Besea (Dave Paterson) and BeeCee (Drew Finerty).

There were many, many ideas of what B.C. actually stands for: Beside Canada, Basically China, Backward Country, Bud Central. That last theme was echoed in a few entries: British Cannabisia (Sandy Stewart), Bastion of Cannabis (Michael Payne) and Best Cannabis (Jeff Germain).

Bill Birneyâs offerings included Borderline Canada, Barely Conscious and Beneath Contempt, the latter having the same number of letters in each word as the current name, meaning a minimum of spatial reconfiguration would be needed for signs on buildings, he noted. Margaret Hantiuk came up with Beautiful Coast and Bring Capital (âold joke, but now the truth as far as our real estate market goesâ).

More than one person put forward Bella Coola as an alternative that would keep the initials intact. While Bella means âbeautifulâ in Spanish, the name Bella Coola is said to derive from the Heiltsuk word for âstranger.â Stephen J. Clarkeâs submission argued that the non-Indigenous among us are âstrangers living in a beautiful land.â

The idea of giving the province an Indigenous name was popular. Salish, Salish Territory and Moksgmâol (the Tsimshian name for the spirit bear) were all suggested. The challenge is that B.C. has dozens of distinct Aboriginal languages. Choosing one would mean snubbing the others.

Several people suggested solving that problem by mining Chinook, the old trading jargon that blended native languages, English and French so that all could speak to one another.

Surreyâs Harpinder Sandhu argued that multicultural synthesis makes Chinook an appropriate source for a new name: âIt truly reflects our integration of native and settler experience up until today.â So, Sandhu asked, how about a new name incorporating Tillicum (meaning people, or family), Nesika (we, us, ours), Skookum (great, strong) or Illahee (land)?

John Ricker had a similar suggestion with a slightly different spelling: Pacific Illahie. Vickie Jackson put forth Chinook Illahie.

Nanaimoâs Paul Walton went Lord of the Rings-ish with his Chinook suggestion, Wakesiah, meaning âa long way offâ or âmysterious, sinister or forbidding.â That has an appropriately Mordor-like feel to it, he said, adding: âAs for our Sauron, take your pick from any number of past premiers.â

From the other side of the Earth (as opposed to Middle Earth), Oriane Lee Johnston emailed from Zimbabwe (formerly Rhodesia) to cheer for change â though she wouldnât stop at retitling British Columbia: âHow about a name change for the newspaper?â

She was echoed by Ron Spence.âDonât you think itâs time to do something about Times Colonist? I mean really, Colonist is so⊠colonial.â

Ditto Janis Wheatley: âWhen I first came to B.C. 14 years ago, it was your newspaper, the Times Colonist, that first impressed me as something of a throwback to the colonial era. Far more irritating, I should imagine, to a First Nations individual or a newcomer to this country.â

Ah, but, a vigorous rear-guard action was fought by a score of readers who argued against revisionist history in general and for the retention of the name British Columbia in particular.

âI couldnât be more against this notion that B.C. needs a new name. Ridiculous!â wrote Deedee Pickell. âHopefully, any serious entertainment of this time and money-wasting foolishness is met with swift and furious rejection! This is nothing more than petty anti-British extremism.â

Steven Turner also championed the status quo, albeit from a different perspective: âAs long as First Nations people are dying in the street, we shouldnât waste money on hollow gestures like renaming the province. Itâs not as if people who are ethno-centric or exclusionary will all of a sudden change their tune when the provinceâs name has changed.â

Fausto Milinazzo weighed in: âWhile our institutions are not perfect, our form of government, the rule of law, free speech, just to name a few things, have evolved from the British.â

Chemainusâs Jane Walton took up the torch: âYes, colonialism created injustices, but it also gave us British democracy, stability and peace. Additionally, if we purge our provincial name due to its association with colonialism, what about other place names such as Vancouver, Victoria, Regina, Prince Edward Island, Hudsonâs Bay or the Mackenzie River, to name a few?â

Also, Walton added, what about those historical figures who treated women as less than equal? Shooing them off the map would mean renaming a lot of lakes, towns, rivers and streets. âAt some point Canadians have to have the courage to say that history serves a purpose and historical revisionism has a limit.â

Central Saanichâs Kevin Frye also subscribes to the value of keeping and learning from warts-and-all history: âCaptains Vancouver, Quadra and Cordova all accepted slavery while Sir John A. was essentially a functioning alcoholic (with a fondness for straight gin) and Queen Victoria kept unpaid âemployeesâ brought to the Palace from the Indian sub-continent. Should we thus also be removing all references to them as a result?â

Michael Halleran leaned on history in presenting his argument, too, though he tilted in another direction. Nova Albion should be the name, he said, reasoning that was what Sir Francis Drake called this coast in the 16th century. âIt was in use for 200 years prior to the Hudsonâs Bay Company establishing their Columbia Department (the ultimate root of Queen Victoriaâs choice of name).â

The name British Columbia was chosen by Victoria (the queen, not the city) in 1858. Last weekâs column said she explained her rationale for doing so in a letter to Sir Edward Bulwer-Lytton. Basically, that letter said the French objected to us getting the name New Caledonia, as they were already using it in the South Pacific. Other names â New Hanover, New Cornwall and New Georgia â were used to describe parts of the territory west of the Rockies but the only appellation applied to the entire area was Columbia, a name already being used in South America and the United States. So Victoria dubbed this colony British Columbia.

The letter was, in fact, written on the queenâs behalf by her husband, Prince Albert, reports Lorne Hammond, the curator of history at the Royal B.C. Museum.

Hammond added a bit of context, too: âPrior to arbitration in 1846 the Hudsonâs Bay Company had hoped that the north bank of the Columbia River would be our border.â Alas, the Oregon Treaty set the border at the 49th parallel, so we didnât get Washington or Oregon. (If youâre wondering why southern Âé¶čŽ«ĂœÓł»Island didnât get swallowed up by the U.S. in the south-of-49 decision, itâs because the Island already existed as its own British colony.)

As an aside, reader Sheila Grigg notes that Bulwer-Lytton, the recipient of Prince Albertâs letter, was an awful novelist whose name lives on in an annual bad-writing contest inspired by his infamous âIt was a dark and stormy nightâ opening line.

But I digress. Back to alternative names for British Columbia.

Dan Kyle of Comox suggested Sasquatchia.

Bill Gillett posed Paradise on Sea.

Terry Foxland, said Thelma Fayle.

Howard Burns wanted Forestland, while Michael Cowan, who argued trees were fundamental to the provinceâs economy, went for Terra Arborea.

âSimply combine the two most expensive places, Oak Bay and James Bay, and you have Joak Bay,â said Hank Sands of Oak Bay.

âI humbly put forward West Alberta,â wrote David Blundon. âI know one Albertan and she likes the idea as much as she likes pipelines.â

North Washington or South Alaska, countered Pat Mulcahy. Canadian California, Roger Purdue wrote from Australia. Peter Klotzâs contributions included New Saskatchewan.

New Democratia, replied Bruce Adnams. Steve Pocock followed that vein: âHow about: âVan Horganâs Landâ (we can change it with each new government to keep things fresh).â

The dreamers dreamed. Ye Xiao suggested Mengjing, which means Fantasy Land in Mandarin. Claudia Kriese opted for Nirvana, Bill Rathlef (who drives a 1963 Lotus Elan) went for Lotusland and David Purser proposed Xanadu (Olivia Newton-John could not be reached for comment).

Douglas Gillespie favoured BellaFerox, which he said is Latin for Beautifully Wild. Since I left my Latin in my other pants, Iâll trust Gillespie on that.

Knoxland, proposed the wise and reasonable Thomas Katz, while the equally sage Brian Wilford of French Creek suggested Knoxville.

And, because somebody had to, Sean David Healey submitted Provincey McProvinceface.