The moral panic that has gripped the western world for a year now — one that has sparked and hastily cobbled Green New Deal proposals — can be traced to a single report.

In October 2018, the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC) issued a special assessment, at the request of the United Nations.

To keep global warming within 1.5 degrees Celsius, as mandated by the Paris Agreement, a 45 per cent reduction in greenhouse gases (GHGs) from 2010 levels will be needed by 2030, the report said.

This prompted Democratic Rep. Alexandria Ocasio-Cortez to warn, “The world is going to end in 12 years if we don’t address climate change,” and a 16-year-old Swedish girl to rocket to fame with her earnest appeals to do something about rising temperatures.

Unlike high-flying, mansion-dwelling Hollywood climate scolds with private jets, at least has tried to walk the talk — refusing to fly, drive in fossil-fuel-powered cars or eat meat.

Asked what, exactly, she would have the adults of the world do, Thunberg simply pointed to the IPCC special assessment and said, “Listen to the scientists.”

So what would a 45 per cent reduction in 10 years take? What would it cost? And what would we all have to give up to accomplish it?

Globally, it would require building the equivalent of four nuclear power plants every single day for the next 10 years, Roger Pielke Jr. recently calculated in Forbes. He didn’t even bother trying to estimate what that would cost.

“We don’t often see these numbers for obvious reasons,” Pielke wrote. “The scale — no matter what assumptions one begins with — is absolutely, mind-bogglingly huge.”

Given that fossil fuels provide 80 per cent of the world’s primary energy, trying to cut that nearly in half in just 10 years would be courting “economic apocalypse,” according to one of the researchers for the Deep Decarbonization Pathways Project.

The deep cuts that are needed globally are feasible, sustainable energy experts say, but not in a single decade.

“I do believe that humanity can decarbonize significantly over multiple decades, which requires action immediately,” said Mark Jaccard, a sustainable energy economist at Simon Fraser University (SFU), who will be one of the authors of the IPCC’s sixth assessment in 2022.

“If you were to ask about the cost of, globally, a 45 per cent reduction by 2030 — yeah, that’s a huge cost,” Jaccard said. “We’re talking decarbonization as costing you a year or two of economic growth over a 30-year period. When you suddenly say over a 10-year period, the costs grow dramatically.”

Even if a breakthrough in fusion energy happened tomorrow, many experts acknowledge that replacing nearly half of the world’s power plants and vehicles with non-emitting energy sources simply isn’t feasible.

“I don’t think it’s the right question to be trying to target minus 45 by 2030,” said Chris Bataille, a climate policy and energy researcher at SFU and an author of the Deep Decarbonization Pathways Project analysis for Canada.

“Instead of thinking in terms of targets like minus 45 by 2030, I would instead suggest — if we really want to do what Greta Thunberg wants — we should be putting all our efforts such that every new thing that gets built, it’s much lower and it’s going toward zero.

“So by 2030 to 2035, you don’t build a building, you don’t build a vehicle, you don’t put in an industry that’s emitting — it’s all zero. And you don’t crush the existing stock, because you’re asking for economic apocalypse.”

Vaclav Smil, the Canadian scientist that the journal Science dubbed “the world’s foremost thinker on energy,” points to the physical limitations of technology, like renewables, to replace fossil fuels on the kind of timelines that have been suggested.

“It took a single decade to come up with entirely new mobile phones,” he writes in IEEE Spectrum.

“But you just can’t replicate that pace of adoption with techniques that form the structure of modern civilization — growing food, extracting energy, producing bulk materials, or providing transport on mass scales.

“While it is easy to extol — and to exaggerate — the seductive promise of the new, its coming will be a complicated, gradual, and lengthy process constrained by many realities.”

The Pacific Institute for Climate Solutions (PICS) recently calculated that transitioning to a 100 per cent carbon-free transportation system in B.C. by 2055 would require a doubling of clean-power generation.

Getting halfway to that target in one-third the time would require taking roughly two million internal combustion vehicles off the road and replacing them with electric vehicles (EVs) in 10 years.

Curran Crawford, the author of the PICS study on electrifying transportation, doesn’t think that’s realistic. Even if governments continue to offer subsidies, and EVs reach price parity with gas-fired vehicles, there is a problem with fleet turnover.

“Things have typically 10-, 15-year lifetimes to them,” Crawford said. “You’re not just going to trash them. It’s that inertia in the system that’s the thing. That’s our challenge if we want to get to 2030.”

While attempts have been made to calculate the cost to society of deep decarbonzation, those calculations are typically based on 20- or 30-year timelines, not 10. So it’s difficult to even try to estimate what it would cost to execute such a radical transformation in just 10 years.

The IPCC itself, however, offered at least one estimate of a cost that the average person can grasp — taxes.

If meeting the 45 per cent by 2030 objective were done strictly through carbon pricing, it would take a carbon tax of U$135 to US$5,500 per tonne ($178 to $7,225 Canadian), the special assessment estimated.

Ross McKitrick, an economist at the University of Guelph, calculates that, in Canada, that would add between $0.41 and $17 to a litre of gasoline in carbon taxes.

Of course, no politician in his or her right mind would try to rely solely on carbon taxes as a climate action tool. But it at least gives consumers an idea of what 45 per cent by 2030 might cost them.

Deep decarbonization will, in fact, require a suite of tools — regulations, subsidies, emissions trading — not just carbon pricing. It will require increased electrification to phase out — or at least reduce the use of — coal and natural gas and move towards a more electrified transportation system.

It would take an investment of $2 trillion over 30 years to meet the objectives in Canada’s climate change plan, the Conference Board of Canada has estimated.

The bulk of that — $1.7 trillion — would be for zero-emission power generation and transmission to facilitate the switch from fossil fuels to electricity. That’s for a 30 per cent reduction by 2050, not 45 per cent by 2030.

That’s roughly $15 billion to $20 billion a year, every year, being invested mainly in nuclear and hydroelectric power.

“You’d need something like 15 or so nuclear plants,” said Conference Board executive director Michael Burt.

Getting that same amount of energy from solar energy would require 6,000 solar farms, taking up a footprint half the size of Nova Scotia, he added.

The Deep Decarbonization Pathways Project estimates the cost of decarbonization would be lower than what the Conference Board calculates. It estimates $13.2 billion in investment is needed every year for Canada to meet its Paris Agreement commitments.

It estimates that for Canada to hit a 30 per cent reduction target by 2030, carbon taxes would need to be at $100 to $150 per tonne by 2030, and the country would need to increase emissions trading imports under the Western Climate Initiative.

It estimated that per capita GDP in Canada would grow from $48,601 per person today to $59,244 by 2030 without climate policies, and to $58,651 with the Trudeau government’s policies. In other words, Canada would sacrifice only one per cent of per capita GDP growth over a decade to meet Canada’s 30 per cent reduction targets by 2030.

Is growth the real problem?

Critics of carbon taxes or renewable energy point to both, and then to increasing global emissions, as evidence that neither works. What they fail to account for is growth.

According to Bloomberg, US$2.6 trillion has been invested globally in renewables — mostly wind and solar — over the past 10 years.

They now account for 11 per cent of the global electricity supply, according to the International Energy Agency, but just two per cent of the world’s total primary energy, according to the renewable-energy think tank REN21.

And though global emissions stabilized between 2013 and 2016, they ticked up again by 1.7 per cent in 2018, reaching 33.1 gigatonnes of carbon dioxide equivalent (CO2e) — the highest ever.

All of the wind and solar power built over the last 10 years might have resulted in significant GHG reductions had the world’s population and economies not grown so much.

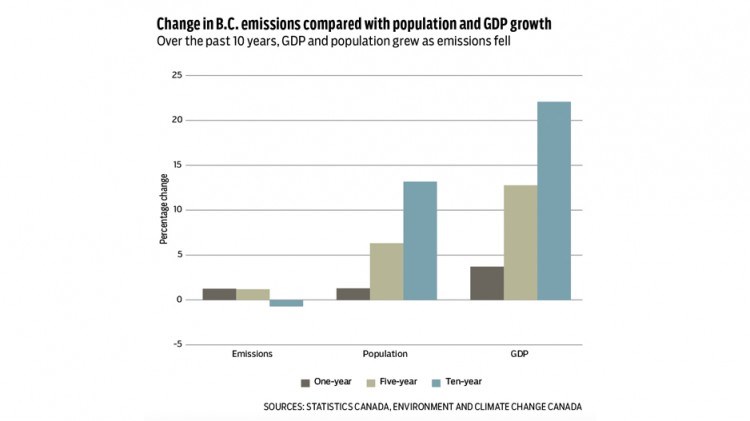

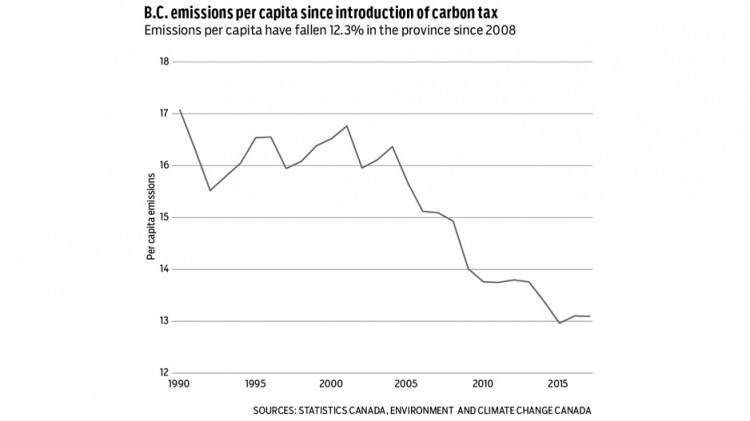

The same can be said of B.C.’s carbon tax. Despite having a carbon tax for more than a decade, B.C.’s emissions today — 63.5 megatonnes of CO2e — have barely budged from the 63.6 megatonnes emitted in 2007.

But B.C.’s GDP grew 25 per cent between 2009 and 2018, and its population grew by 600,000.

B.C.’s per capita emissions intensity has actually gone down significantly since the carbon tax was introduced. Per person, British Columbians produce fewer GHGs than they did 10 years ago.

Generally, there is a correlation between prosperity and emissions. The countries with the highest per capita GDP tend to have higher per capita GHG emissions. The exceptions are those countries, like the Netherlands and Sweden, that have managed to decouple emissions from economic growth — continuing to expand their economies while reducing emissions.

The deepest declines in GHGs over the past decade came as a result of a global recession, though a switch from coal to natural gas for power over this time period also accounted for some significant GHG reductions in the U.S.

Climate goals put consumerism in the crosshairs

Population growth, economic growth and hyper-consumerism are really what has been driving emissions through the roof over the past few decades.

Put in a way that, say, the average teenager might understand, cutting 45 per cent of emissions by 2030 could be accomplished by taking half of everything you own and half of everything you earn and giving it up.

You could start by forcing your parents to downsize from your 2,600-square-foot home into a 1,300-square-foot home. Or, have them invest in a highly efficient natural gas furnace, or heat pumps, and triple-paned windows.

If your family owns two cars, get rid of one, or buy electric vehicles. No more flying, except for funerals. Staycations must become the new norm. Learn to live with half the clothes you wear (don’t even think of buying fast fashion — its carbon footprint is huge), and cut your consumption of meat in half.

And that iPhone of yours — maybe give that up, too. It’s not so much the embedded emissions of making it that are the problem — about 76 kilograms of carbon dioxide equivalent (CO2e), according to Apple’s own calculations — but the energy consumed by the servers that power your apps.

Most of those servers are based in the U.S., which derives 64 per cent of its power from coal or natural gas. As a result, a single photo shared on Snapchat generates about 0.1 grams of CO2, according to one calculation done by Inverse.

And you don’t even want to know how much CO2 you put in the atmosphere when you binge on Netflix (but we’ll tell you anyway): 3.2 kilograms of CO2e per hour of viewing, according to The Shift Project.

The think tanks said video streaming generated one per cent of the world’s GHG emissions in 2018 — 300 million tonnes of CO2e — and digital technologies in general accounted for four per cent of global emissions.

So while you are getting rid of your iPhone and half your clothes, walking to school instead of getting a ride, and taking no more vacations that require air travel, cut your Netflix and chill time in half, as well. Then convince all of your friends’ families to do the same.

Read the original article .