Yoris Naikambo’s love for his mom knows no bounds, not even the vast expanse of the world’s largest ocean.

This much we know.

Who Naikambo is, or was, is a mystery the Courier is now trying to piece together.

It’s a needle-in-haystack scenario that started almost two decades ago somewhere near Indonesia. Sixteen years and almost 11,000 kilometres later, the story shifts first to Haida Gwaii and then on to Vancouver.

All of this, after travelling across the largest tract of open water and uninhabited space on Earth.

A message from 2003

Naikambo’s tie to the West Coast began in August 2019. University of B.C. forestry student Nikki Saadat was harvesting seaweed near the village of Queen Charlotte, off the central coast of Haida Gwaii.

The day’s end saw the boat headed back to shore when an empty plastic bottle was found floating in the surf.

Thinking it was garbage and compelled to do the right thing, crew members slowed down to retrieve what appeared to be an obscure looking, one-litre bottle devoid of any labels or markings.

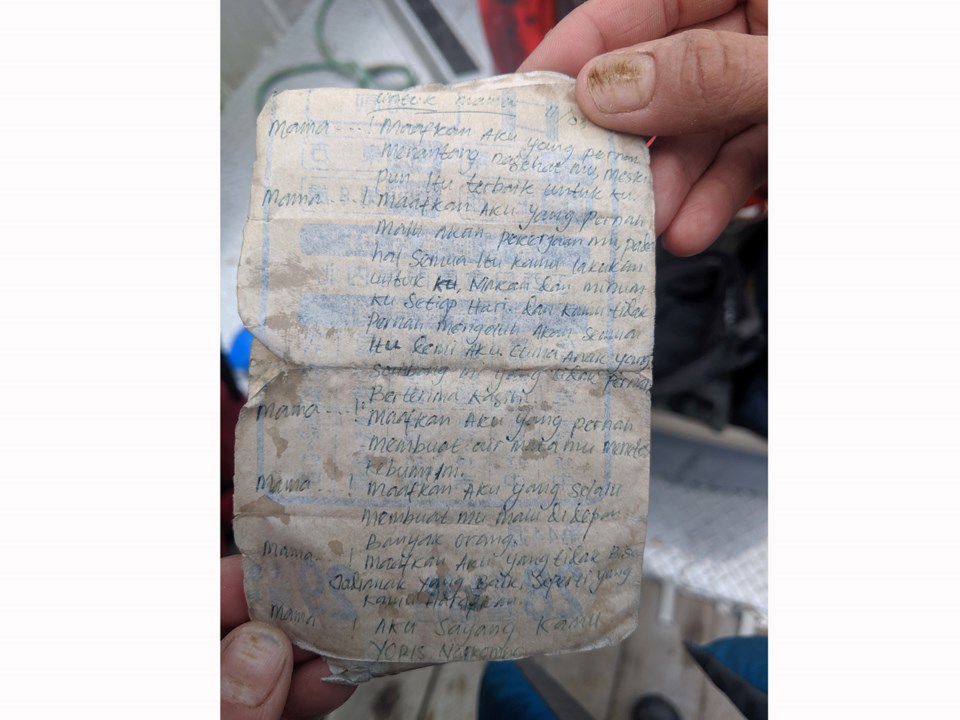

“It was a beautiful day out,” Saadat recalled. “We swooped the boat around so we could pick it up and we saw there was a note inside of it. You could see the ink had kind of faded a bit.”

Nothing was to be gleaned from the note initially, other than the date: November 2003. Crew members took photos, went back to shore and carried on with their lives. In Saadat’s case that meant coming home to �鶹��ýӳ��and starting a new semester. The note and bottle remain with Saadat’s boss in Haida Gwaii.

The photos drifted from memory, until Saadat recently showed them to classmates. The language was identified as Indonesian and Saadat’s classmates suggested that particular type of bottle is ubiquitous in southeast Asia.

Saadat provided the Courier with a translation, which was then verified by many others who speak Indonesian.

Flowing down the page in poetic form, Naikambo spoke the most universal of truths.

I love you mom. I’m sorry mom.��

“M������…

Forgive me for not listening to your words of advice, even though those were what’s best for me.

�Ѳ�����…

Forgive me for being ashamed of your work, even though you did it all just for me, to provide meals on the table everyday. And, you’ve never complained about any of that, but you have me, an arrogant son who doesn’t know how to be grateful.”

“It makes me think of a mother’s love and how universal that is,” Saadat said. “All of us have that time when we’re young and we all have that ego that we don’t realize how selfish we may be being. And then you grow up and you look back and you’re like, ‘Wow, my parents were so selfless and did everything for me.’”��

Detective work

Cursory searches online and through social media turn up no one with the name Yoris Naikambo.

As such, the Courier contacted members of the Indonesian community both locally and abroad to understand the possible motivations, cultural references used, and who Naikambo is, or was.

Liza Wajong came to Canada in 1999 and is a long-standing member of PERMAI-BC, an Indonesian cultural group based in Vancouver.

She spoke to the Courier in her West Fourth Avenue coffee shop, Nusa, and was taken with emotion as she read the sign-off in which Naikambo tells his mom he loves her.

“I think it’s sad, it’s so sad,” Wajong said. “His mom probably never got a chance to read this letter. He misses his mom so much.”

Wajong then quickly puts her detective hat on. Yoris is a man’s name. His use of the word “mama” rather than the more common term “ibu” suggests he’s probably Christian, born into modest means and likely raised in a rural setting in east Indonesia. ��

There’s a good chance Naikambo wrote and cast the letter off from somewhere outside the island nation. He was likely working and earning more in a foreign country and sending money home.

That Naikambo didn’t send the letter through the mail suggests he could have been working on a cruise ship, according to Wajong. She did a quick search online and suggests his surname may be local to the eastern Indonesian province of Maluku.

This is a bit of a sticking point for Paulus Bunadhie, who offered to assist the Courier in its research after a callout was made on social media. Reached via Facebook Messenger, the Nanaimoite left Indonesia for Canada in 1987 at the age of 13. His family remains there and Bunadhie returns for a month each year.

“Based on the name, it’s most likely from the Island of Java,” Bunadhie said. “South Indian Ocean side I bet.”

Otherwise, Bunadhie’s thoughts on the find are largely in lockstep with Wajong.

Despite the morose tone of the missive, neither believes it to be a suicide note — instead, they suggest it’s a confessional written by someone who really misses his mom.

Suicide, Bunadhie suggested, is rare and taboo in Indonesia.

The text flows in a way that’s characteristic of Indonesian poetry or perhaps a lyric for a song. Like Wajong, Bunadhie surmised his countryman wrote the poem from somewhere else in southeast Asia. ��

“Very common for young Indonesians to be able to provide more opportunities for the family. Average monthly income is only $100 to $200 per month,” Bunadhie said.

Bunadhie took great interest in the paper the poem was written on, suggesting it came from Korea or Taiwan.

Zooming in and reading in minute detail, Business in �鶹��ýӳ��reporter Chuck Chiang recognized the paper to be from a fortune telling calendar. The poem was written on an entry dated for Sept. 28, 2003. It was a Sunday, one of the few in recent years that saw that particular date land on a Sunday — meaning, the paper was printed in 2003 and published just weeks before Naikambo wrote on it.

Chiang’s analysis narrowed the search for the paper’s origin down to four possibilities: Hong Kong, Malaysia, Taiwan or Singapore. Chiang’s hunch is based on the fact the text was written in traditional Chinese characters still widely used in those countries.

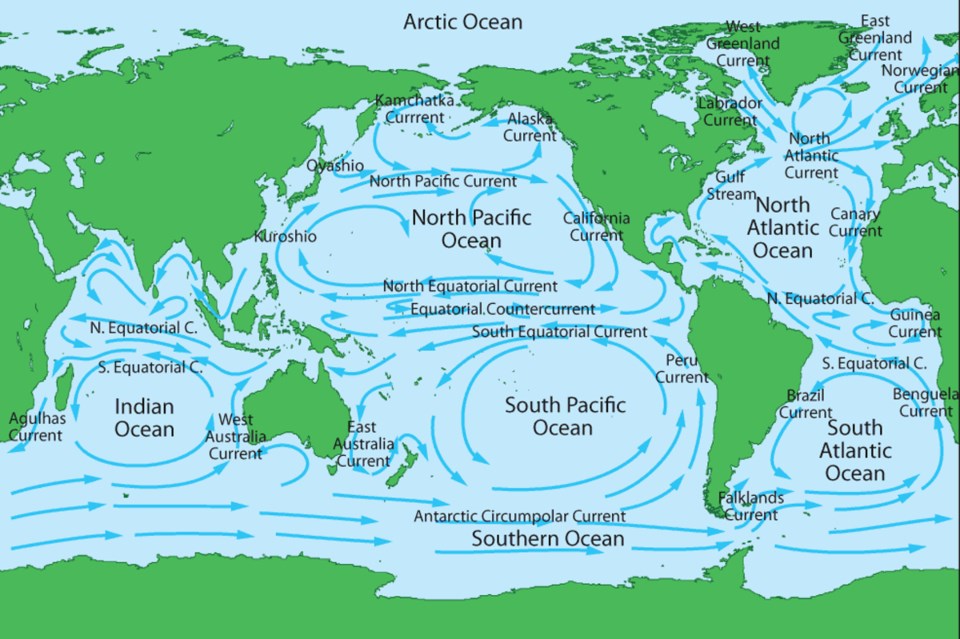

Those countries' geographic locations are key to explaining how the bottle ended up near Haida Gwaii, as some ocean currents originating near southeast Asia travel throughout the northern Pacific Ocean — in line with the Alaska, B.C. and the western seaboard of the U.S.

“Surface currents are such that it is plausible for a plastic bottle to make it from Indonesia to Haida Gwaii,” confirmed Dr. Karen Kohfeld, a professor in resource and environmental management at Simon Fraser University.

Kohfeld also confirmed that a small plastic item such as the bottle in question could remain intact despite being exposed to salt water for 16 years. She knows this because of a now infamous story of a in 1992. The boat contained plastic bath toys, some of which are still washing up on shores across the globe to this day. The incident helped scientists better understand ocean currents and is still referenced in current research.��

Search continues

All of this brings us back to Saadat’s next step. She’s sent emails to Indonesian media outlets in hopes the story gains traction closer to home, but there have been no bites yet.

Saadat isn’t even sure if Naikambo or his mother are still alive. Natural disasters have plagued that part of the world in the intervening years since 2003: earthquakes, tsunamis, typhoons, flooding and drought. The earthquake that hit the region on Dec. 26, 2004 killed close to 225,000 people and the Indonesian death toll ranges between 130,000 and 170,000.

Regardless of Naikambo or his mother’s fate, everyone who spoke to the Courier wants some closure: confirming the identities of the people involved or an update on their whereabouts.

If nothing else, it’s a chance to radiate to a larger audience the love a son felt for his mom on an autumn day in 2003.

“I don’t know what the universe is trying to tell us,” Wajong said. “Somehow this message made its way all the way here. If it’s meant to be, someone may pay attention in Indonesia.”

@JohnKurucz

��

��

��

��

��

��

��

��

��

��