The B.C. governmentвҖҷs pandemic-influenced move Thursday to allow drug users to take home вҖ” and have delivered вҖ” prescribed medications as alternatives to poisoned street drugs has been praised by harm reduction advocates across Vancouver.

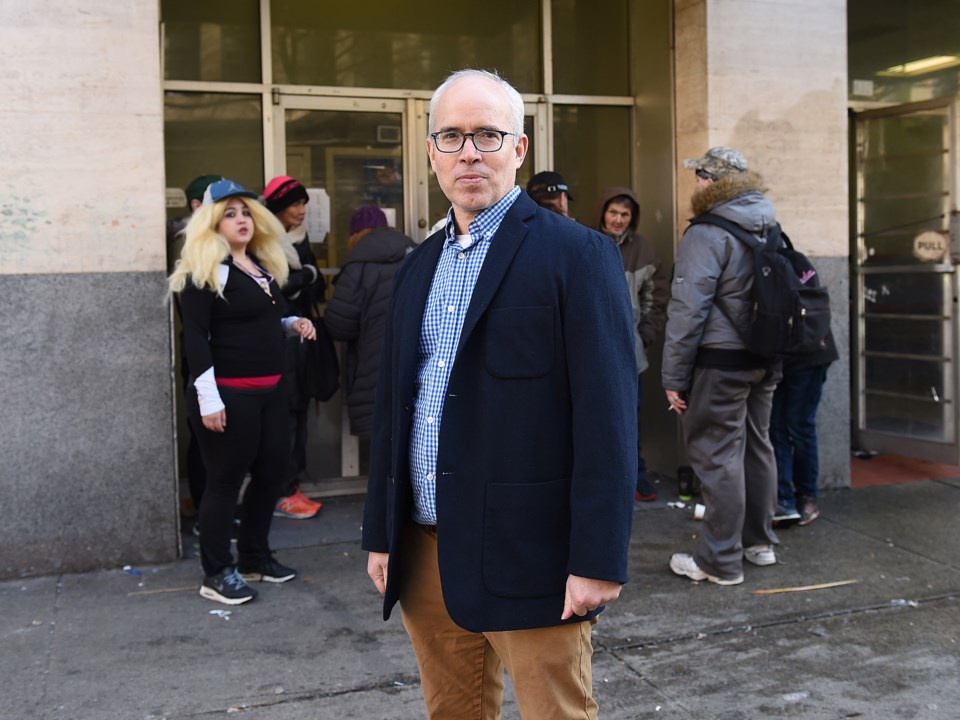

Donald MacPherson is one of them.

But the executive director of the Canadian Drug Policy Coalition has a question to go with the welcoming news: How long will the provision last?

The question came to MacPherson after reading the federal document that allowed the provincial government to relax guidelines for drug prescription during the pandemic.

The document states the exemption under section 56 of the Controlled Drugs and Substances Act expires on the earliest of the following dates: Sept. 30, 2020; the date that it is replaced by another exemption; the date on which it is revoked.

вҖңI would like to think that we would be transitioning out of this emergency phase into another phase that actually addresses the pre-existing conditions вҖ” pre-COVID-19 вҖ” of the toxic drug supply, and the need for people to continue to access pharmaceutical grade substances,вҖқ said MacPherson, the cityвҖҷs former drug policy coordinator.

His worry is that such a transition wonвҖҷt occur.

That conclusion is based on what happened to two ground-breaking drug trials in В鶹ҙ«ГҪУі»ӯrun between 2005 and 2014 that were not extended by government and made permanent.

NAOMI, SALOME

The North American Opiate Medication Initiative and the Study to Assess Longer-term Opioid Medication EffectivenessвҖ”known more commonly as NAOMI and SALOMEвҖ”were praised by public health and addiction medicine doctors as successes.

Trial participants reported improved mental and physical health, less or no dependence on street drugs such as heroin and a reduction in crime committed over a month.

Since those trials, Mayor Kennedy Stewart, doctors, harm reduction advocates and even police have lobbied for a widespread safe, regulated supply of drugs for chronic drug users in Vancouver.

Smaller scale programs operate at clinics and hospitals, including where some patients are able to carry home long-acting morphine, Suboxone and methadone. In January, Dr. Mark Tyndall'sМэ MySafe Project, a hydromorphone pill dispensing machine, began operating in the Downtown Eastside to a half dozen clients.

To have more access to medications approved in the middle of a pandemic is bittersweet for MacPherson, who wants a national safe supply strategy, but noted B.C. is the only province to adopt the exemption announced last week by the federal government.

вҖңItвҖҷs amazing that it takes a global pandemic to move the dial on this,вҖқ he said. вҖңItвҖҷs just bewildering, but weвҖҷll take it.вҖқ

The exemption, and the corresponding action from the B.C. government, is in response to concurrent public health emergencies active in В鶹ҙ«ГҪУі»ӯand across the province.

The pandemic coupled with the overdose crisis presents unprecedented risks for drug users unable to self-isolate, keep their physical distance from people or quarantine to prevent the spread of COVID-19.

That group includes people who are homeless and living in shelters and single-room-occupancy hotels, which are often set up with shared bathrooms and common areas, including kitchens.

Hydromorphone and dextroamphetamine

Under the new provision, which is expected to have more of an impact in the Downtown Eastside that any other part of the province, health care providers are able to get safe, prescription alternative medications such as hydromorphone and dextroamphetamine into hands of drug users not in a treatment program, or who regularly visit a doctor.

The focus of the new guidelines is not to treat drug users, but support them. Мэ

The medication is restricted to oral doses and excludes prescription injectable heroin, which continues to be offered to about 100 patients at the Crosstown Clinic in the Downtown Eastside.

Pharmacies can have employees deliver medication, extend prescriptions, transfer prescriptions to other pharmacists and allow prescribers such as a doctor to refill a prescription over the phone.

Initial prescriptions can be made to last 23 days.

This means the common practice of drug users having to ingest addiction-fighting medications in front of a pharmacist doesnвҖҷt apply.

Clinics are also set up to offer вҖңtelemedicineвҖқ for clinical assessments, which means a patient and doctor can talk to each other via a computer to accelerate a personвҖҷs access to medication.

The goal is to keep drug users from overdosing while simultaneously protecting them from getting infected with the virus, which had been detected in 792 people in B.C., as of Friday.

Judy Darcy, the Minister of Mental Health and Addictions, said government has worked flat out to put the new guidelines in effect, noting it was only last week that the federal exemption was announced.

вҖңIf people have to go to a pharmacy every day, theyвҖҷre at greater risk and the communityвҖҷs at greater risk,вҖқ Darcy told the Courier Friday.

вҖңHopefully it will be an opportunity for more people to get on safe prescription medication than the folks who are already on.вҖқ

Darcy said B.C. has led the country in getting safe prescription medication to drug users and was rolling out more pilot projects prior to the COVID-19 outbreak.

The minister acknowledged the challenge of mobilizing and training more health care professionals to meet the needs of drug users during the pandemic.

ItвҖҷs an equal challenge to get chronic users assessed and provided with the medication they need, she said, urging family and friends of people who use drugs to spread the word of increased access to health care providers and medications.

вҖңWhile we have to physically distance, itвҖҷs not a time for social isolation, itвҖҷs not a time when we push people away,вҖқ Darcy said.

вҖңThereвҖҷs already too much stigma surrounding people who use drugs, people who struggle with an addiction every day. This is a time to be even more compassionate and to reach out to them.вҖқ

To MacPhersonвҖҷs concern about the safe supply provision being a temporary measure, Darcy wouldnвҖҷt say whether she would urge the federal government to extend the exemption beyond Sept. 30, or request it be permanent.

She said she didnвҖҷt have a crystal ball.

вҖңRight now weвҖҷre focused on the tasks in front of us, and so are they,вҖқ the minister said. вҖңThatвҖҷs what we have the ability and the energy to do at this time.вҖқ

Added Darcy: "We're dealing with one public health emergency on top of another in B.C. today. We are focused on saving lives, and saving lives and protecting peoples' health and the community's health in the face of an unprecedented pandemic. That's what we're focused on."

The B.C. Centre on Substance Use developed the guidelines, which were reviewed by the provincial government and Provincial Health Officer Dr. Bonnie Henry, a strong advocate for a regulated supply of drugs and decriminalization.

Cheyenne Johnson, co-interim executive director of the B.C. Centre, acknowledged the ongoing work of the provincial government and others to reduce overdose deaths вҖ” and noted fewer deaths were reported last year вҖ”but said overdose calls remain steady.

вҖңWeвҖҷve thrown many things at the crisis, including expanding treatment, harm reduction, recovery supports and we havenвҖҷt seen a huge substantial change,вҖқ Johnson said.

вҖңThis [move by government] is the next level. This kind of moves towards the regulated drug supply to provide people with safer access, so that people can use drugs if they choose to, and not expect to die because itвҖҷs contaminated with fentanyl.вҖқ

The guidelines warn the continuation of the pandemic may result in the street drug supply becoming "significantly more adulterated and toxic, based on limited importation and availability, and illicit substances may become significantly more difficult to procure."

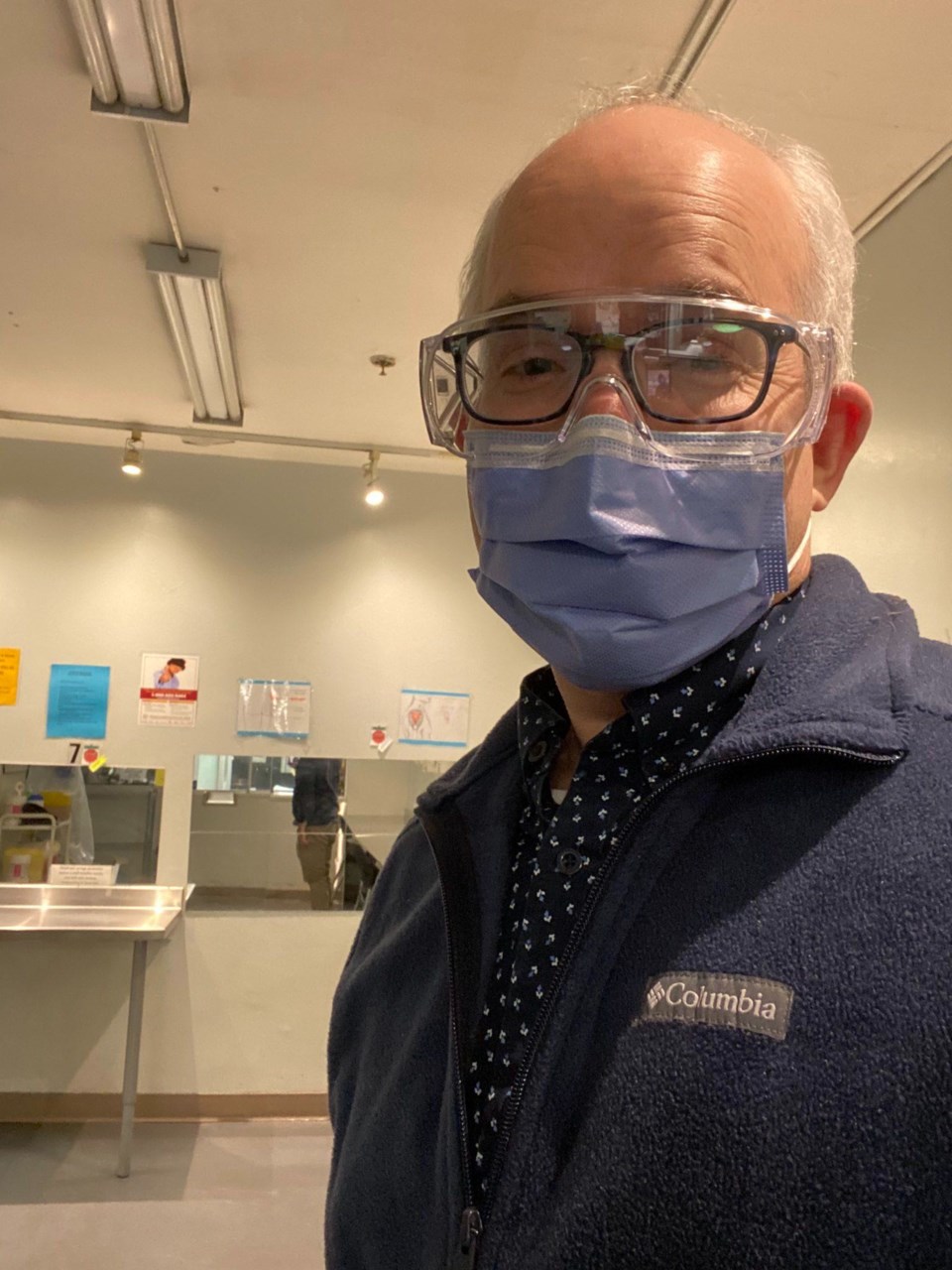

Meanwhile, at the Crosstown Clinic at Abbott and West Hastings streets, patients of the prescription heroin program still must attend the facility to inject the drug.

In most cases, that means patients must visit the clinic three times per day, an onerous requirement made even more difficult during a pandemic when people are told to stay home.

Dr. Scott MacDonald, physician lead at Crosstown, said physical distancing has been put in place in the clinic, along with staff wearing personal protective equipment.

The assumption, he said, is COVID-19 is circulating in the community.

вҖңMy greatest concern is death,вҖқ MacDonald said in an email Friday.

вҖңOur patients are at risk. Ninety-four per cent of our patients smoke and there is a high prevalence of COPD, which increases the risk of severe disease from COVID-19. We have supported a small number of patients who expressed a need to self-isolate at home to reduce their risk.вҖқ

MacDonald said he welcomed the move to relax regulations around safe supply, but added that it will take time to get prescriptions to people, saying it wonвҖҷt happen overnight.

вҖңMany folks have had bad experiences with health care and do not trust the system,вҖқ he said.

вҖңWe need to attract more folks into care. The treatment with most evidence for opioid users who continue to inject street opioids is supervised injectable opioid agonist treatment with diacetylmorphine and hydromorphone.вҖқ

Added MacDonald: вҖңThis will be a marathon, not a sprint. I hope plans are in place to expand the full spectrum of evidence-based options, including prescription heroin.вҖқ

The reason Crosstown exists is because of the success of NAOMI and SALOME.

In fact, both studies were run out of the clinic, which used to be a bank, with its vaults still in use by staff at Crosstown.

The clinic also exists because advocates won an injunction in B.C. Supreme Court in 2014 that allowed the program to continue, despite efforts by the-then Stephen Harper government to shut it down.

That court decision allowed the transition of the SALOME trial to Crosstown, which began its first treatment with prescription heroin in November 2014.

More than 400 people are on a wait list for the clinic.

вҖңWe were already at capacity prior to a second public health emergency,вҖқ MacDonald said.

вҖңSupervised injectable opioid agonist treatment could be provided in supported housing units with people at risk for irreparable harm and death from both opioid injection and COVID-19.вҖқ

B.C. recorded 981 overdose drug deaths last year, with 245 of those in Vancouver. The pandemic has claimed 16 lives in B.C. since the outbreak in January.

@Howellings

Мэ

Мэ

Мэ