Blake Butler is a PhD candidate at the University of Western Ontario whose research looks at the history of snow-making at Canadian ski resorts. In this story submitted to the North Shore News, he looks at Grouse Mountain Resort's pioneering role in bringing snow-making to B.C. Butler currently lives in Vancouver. Â

Snow-making has started again at Grouse Mountain.

Last week, resort officials announced that temperatures had dropped low enough for the system to be switched on. This – coupled with the 15 centimetres of snow that fell night Nov. 24 – had the resort in high hopes. So long as the temperatures remain below freezing, the system will continue to produce snow over the following days and weeks. “Pull your gear out from your closet and be ready,” proclaimed the Grouse Mountain website, “winter is on its way!” And indeed, on Nov. 30, the resort officially opened for skiing.

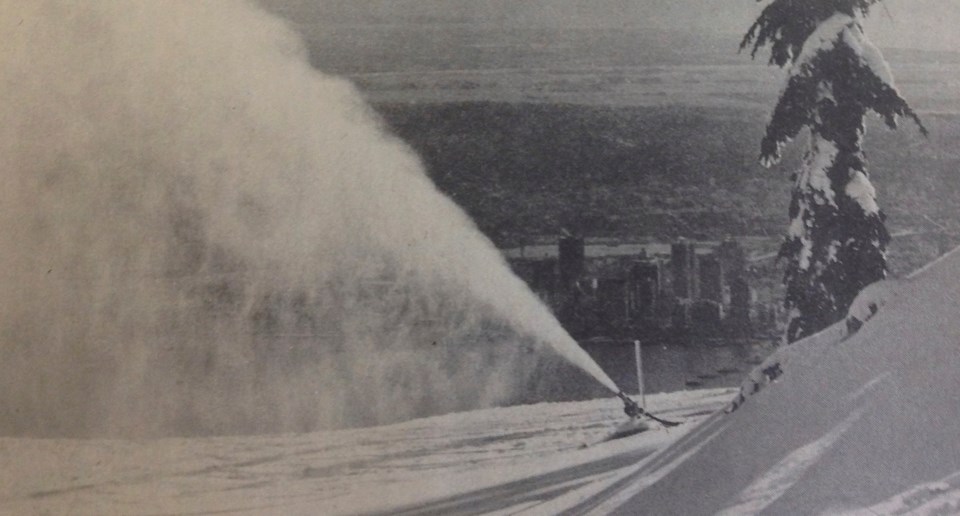

Snow-making has been a big part of Grouse’s skiing operations for the past 46 years. In 1973, Grouse installed the first snow-making system in British Columbia. Consisting of 27 snow guns, 117 water hydrants, and 10 miles of piping, this system was at the time the third largest in the world.

Snow-making seemed unnecessary in B.C.’s Coastal Mountains prior to the 1970s. While Eastern Canadian resorts increasingly relied on snow-making for their operations, B.C. ski resorts like Grouse trusted that nature would continue to provide them with endless snow. This thinking began to change during the 1969-70 ski season. In his report to shareholders, Grouse Mountain’s director John Hoegg lamented how “throughout the decades that records have been maintained on Grouse Mountain, there is not one year that shows an average snow depth lower than the winter of 1969-70.” In late January 0f 1970, the Â鶹´«Ă˝Ół»Sun reported that Grouse had received only five inches of snow that month, well below its seasonal average. This low snowpack limited Grouse’s operations. The mountain’s popular ski run The Cut was open for only 10 days that year, compared with over 150 days the previous year. These poor conditions led to reduced skier traffic and a net loss of $50,000 for the company.

While conditions improved the following year, Grouse’s luck was short-lived.

“It is difficult to imagine facing yet a more depressing winter environment just three years later,” complained an exasperated Hoegg, “but such was the case during the most recent 1972-73 season.” Warm temperatures and rain kept the mountain closed during Christmas week, a phenomenon that had not occurred since Grouse Mountain Resorts Ltd. acquired the mountain in 1964. While conditions improved later that season, this early closure again resulted in lost revenue and below-average traffic on the mountain.

This was the final straw for Grouse’s management team. In April 1973, Grouse announced its intention to install a new snow-making system that would pump water from nearby Kennedy Lake. With this system, the company could cover The Cut with a one-foot deep layer of snow in just over 24 hours. Hoegg explained, “this progressive step will have a dramatic positive influence … bringing an era of predictability to customers’ utilization of the mountain.”

Vancouver-area residents responded positively to Grouse’s decision. North Â鶹´«Ă˝Ół»Mayor Ron Andrews described the project as exciting and unique. Both the Sun and the Province congratulated Grouse Mountain’s management for the massive undertaking and commended their forward-thinking vision.

Grouse did not make use of its new equipment for the next few years, thanks to a slower-than-expected installation period, warmer early season temperatures, and an abundance of natural snow. The system finally showed its usefulness in 1975. On Nov. 20, the resort announced that The Cut was open, thanks to Grouse’s snow-making system. Snow-making kept the resort in operation during that year’s mild Christmas season.

Grouse’s system once again proved beneficial during the “snow drought” of 1976-77. That season, B.C’s ski resorts faced unseasonably warm temperatures and historically low precipitation totals. Ski resorts across the province, including Whistler Mountain, had to temporarily close their operations. The situation was little better at Grouse. On Feb. 1, 1977, the resort measured only two centimetres of snow at its peak – its lowest snowpack in recent memory. But, Grouse remained in partial operation thanks to its snow-making system. Concentrated snow-making on the Paradise run kept it open to skiers for weekend use.

Grouse’s equipment even helped introduce other resorts to the value of snow-making. In February 1977, Grouse loaned Whistler one of its snow guns, allowing that resort to create snow and to resume partial operations. Four years later in 1981, Grouse again loaned snow guns to the recently opened Blackcomb Mountain to help that resort combat a low snowpack. Whistler and Blackcomb both installed their own snow-making systems in 1982 and 1987, respectively.

Grouse pioneered snow-making in B.C. Indeed, Grouse’s early success with snow-making showed the benefits of this equipment and inspired other B.C. ski resorts to install their own systems. Today, many resorts rely heavily on snow-making, particularly for runs at lower elevations. Snow-making will become even more important this century, as scientists predict that average winter temperatures will continue to rise and that total snowfall will decline on the North Shore mountains over the next 80 years. For resorts like Grouse, snow-making, once an oddity on B.C.’s mountains, may soon become the only reliable source of skiable snow.