They held a marijuana info session at the Victoria airport Thursday: free advice, free coffee, free muffins for travellers wanting to know how legalization will affect them. The muffins went fast.

Maybe people thought they were, you know, those kind of muffins.

No, no, edibles won’t be legal for a year, which is one of the things those dispensing the advice — representatives of Island Health, the RCMP, the CRD, the Commissionaires, the airport authority — were able to tell those who stopped by.

Mostly the questions and answers were pretty straightforward.

Where can people smoke weed? By and large, in the same places they can smoke tobacco, which in the airport’s case means two designated spots by shelters across the road from the terminal.

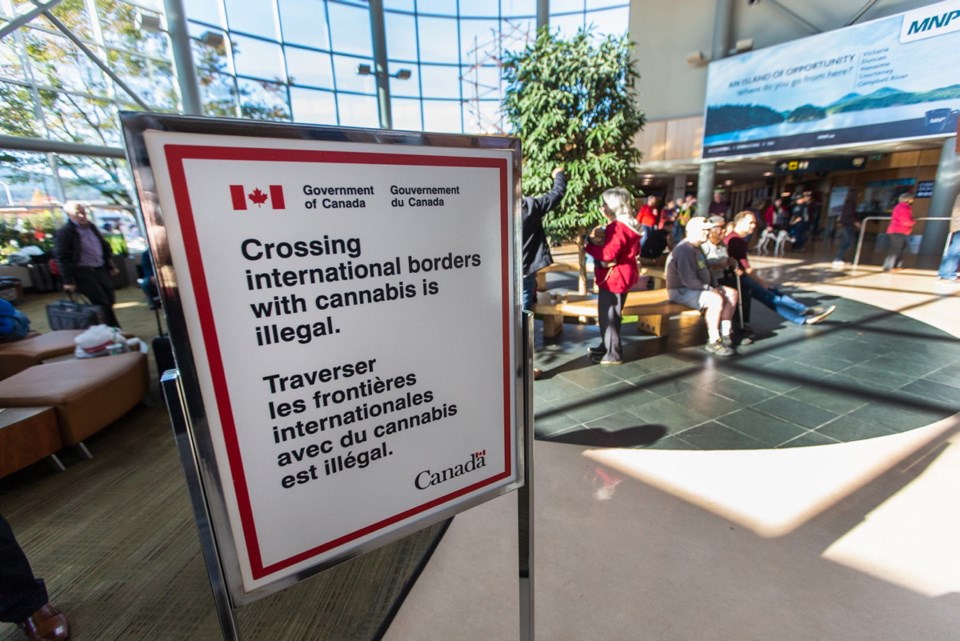

May you fly with marijuana? Not across an international border. Canada’s laws mean nothing in other countries.

Even though certain states, such as Washington, have legalized recreational pot, U.S. federal law still says possession is illegal — and the border agents work for the feds.

(Also, there’s always the chance bad weather or safety issues could divert your flight to a less pot-friendly jurisdiction. “You don’t always end up going to the place you expect to land,” says the RCMP’s Cpl. Chris Manseau.)

How about on a plane inside Canada?

Yes, adult passengers on domestic flights will be allowed to bring up to 30 grams of dried cannabis or its equivalent.

Yes, adult passengers on domestic flights will be allowed to bring up to 30 grams of dried cannabis or its equivalent.

(The Mounties have detailed those equivalents — seeds, fresh pot, cannabis in non-solid concentrates and so on — in a matrix so complicated it would buckle the knees of a rocket scientist.)

It’s not like the guy at the security gate will be sitting there with a set of scales, ready to enforce the 30-gram rule, though.

In fact, the security people don’t really care about marijuana at all.

They screen for the threats detailed on the Canadian Air Transport Security Authority’s list of prohibited items, not pot.

The airport authority says it’s up to the RCMP to enforce marijuana law.

The Mounties no longer have a permanent presence at the airport, though, so …

Ah, less than a week away and we’re still scrambling to figure out how legalization will shake down, finding as many grey areas as black and white.

Good on those who took part in the airport info session for taking the initiative to answer the public’s questions, but with five days to go, some organizations are still making up policy as they go along.

CATSA says its response to the changes in law are evolving.

And the U.S., which had been threatening to refuse to admit Canadians who are employed by the marijuana industry, has quietly done an about-face and as long as they weren’t travelling for work.

Elsewhere, employers are still figuring out how to respond to legalization; that it will follow Air Canada’s lead in barring those in certain “safety-sensitive” jobs — pilots, cabin crew and aircraft maintenance engineers, among others — from indulging at all.

That last one relates to one of the thorniest issues: the lack of an easy, certain way to tell if someone is stoned. Urinalysis, the most common method of employee-testing, can detect metabolites of a drug in your system but isn’t as good at showing impairment. Metabolites of marijuana can hang around for weeks, unlike those of alcohol or cocaine, which disappear within days of consumption. People can test positive for marijuana long after they’re high. In consequence, employers err on the side of caution and opt for zero tolerance.

Police are similarly challenged in nailing drugged drivers. Ottawa has approved a pricey new saliva-based roadside screening device, but it is neither widely available nor proven here. Nor are many police forces set up to do the blood tests required to lay charges under Canada’s new drug-impaired driving laws (and good luck finding a nurse to draw a blood sample at 4 a.m. if you’re the cop in Abandoned Tractor, Sask.). Many forces depend on certified officers using field tests similar to the old “now walk in a straight line while touching your nose” way of detecting drunk drivers.

Five days to go. Are we ready? Take a deep breath.