It was a game of “what if?” played with millions of people for billions of dollars.

What if Â鶹´«Ă˝Ół»hosted the 2010 Winter Olympics? What if this on-time, on-budget spectacle bequeathed the city a sea change in its culture, community and international reputation and made the fun-deficient municipality more lovely, loved and prosperous?

Looking back at the Â鶹´«Ă˝Ół»Olympics and the way they were sold, documentarian George Orr has mixed feelings.

“For them, the Games were the biggest thing in the world,” he says of its organizers. “For the rest of us it was just two weeks [where] you can’t drive downtown and there’s interesting stuff on TV.”

In the 74-minute documentary Chasing the Dream showing Thursday on CHEK TV, journalist and former federal Green Party candidate Orr dives into the years of wheeling, dealing, soft- and hard-selling that led to the event that brought us Quatchi and Sidney Crosby.

Premier Gordon Campbell was a major figure in bringing the Games to B.C., as was Â鶹´«Ă˝Ół»Olympic Organizing Committee president John Furlong. But from Orr’s perspective the engine behind the pump, pomp and circumstance was West Vancouver’s Jack Poole.

Raised in Saskatchewan, Poole became a Â鶹´«Ă˝Ół»real estate tycoon whose approach to public relations ran closer to self-demotion than self-promotion.

“He did not like being on camera or in the news,” Orr reflects.

Poole thought the story should be about Furlong while Furlong thought it should be about the event itself.

“It’s hard to tell a story about an event,” Orr notes. “It’s easier to tell a story about people.”

Early in his career, Orr was instructed by radio great Jack Webster in the correct disposition for journalism: be cheerful and as persistent as a raccoon trailing the scent of peanut butter.

Orr asked Poole, Furlong and Campbell for interviews. And asked again.

“It took, on average, about three years to get each of the major characters to sit down and talk to me,” he says. “I finally convinced [Poole] that I wasn’t going to go away.”

Orr also caught a break. Philanthropist Darlene Poole, having worked with Orr at CKNW in the 1970s, vouched for her old colleague to her husband.

Orr would amass 600 hours of video of press conferences, protests, celebrations and civil disobedience. But the story, he realized, was Poole.

They talked about the “nirvana” of West Â鶹´«Ă˝Ół»and about the games Poole wouldn’t live long enough to see.

Despite years of sidestepping interviews, Poole seems relaxed and forthcoming – if a bit self-deprecating – when chatting with Orr.

Vancouver’s Olympic campaign needed a high-energy, bilingual travel lover, Poole recalls.

He says he began his first meeting with the search committee by saying: “I struggle with English. I’m 68 years old and I hate travel … Is the meeting over?”

Perhaps impressed by Poole’s honesty or his great wealth and connections, Poole got the job and set about finding a crew that could organize, strategize, and sell the games to British Columbians.

Marketing expert Jeannette Hanna advised the Olympic committee to be transparent.

“Don’t over-promise here because that’s a death knell,” she tells Orr.

The strategy seemed solid. But, after the Â鶹´«Ă˝Ół»Sun wouldn’t publish VANOC’s vision statement, the organizers changed course, Orr reports.

“They had tried candid open transparency and it didn’t work.”

Following a meeting with the organizers of the 2000 Sydney Olympics, the committee began to realize that any controversies and dramas preceding the Olympics would be relegated to opening act status. What mattered was the euphoria of the event.

So, VANOC focused on “happy message stories” they could control, Orr says.

During one press conference an athlete faints. Not wanting to focus on the negative, the VANOC spokeswoman continues talking as though an athlete weren’t passed out by her feet.

Board meetings were closed to the public. And when Â鶹´«Ă˝Ół»Mayor Larry Campbell pushed for a referendum to find out if people really wanted the Olympics, it was not appreciated.

“Poole hadn’t wanted to risk community support with any public consultation, so he chewed Larry Campbell out,” Orr narrates.

Making the documentary was a challenge, Orr says.

Because organizers saw him shooting but never saw what he shot, they were uneasy.

“They don’t like me,” he says. “They didn’t know what I was up to and they found that disturbing.”

Orr also found it challenging to pin down anyone from VANOC about just how much the games cost.

“They were very vague and still are about what was spent and how much was spent and where it was spent,” he says.

His best estimate, he says, including security costs and the new Sea-to-Sky highway, is $8 billion.

That new highway – and the controversy surrounding it – features heavily in Chasing the Dream.

“Because the skiing events would be held 100 kilometres north of Â鶹´«Ă˝Ół». . . they saw this precarious old two-lane cliffhanger as being a dealbreaker and no matter what the cost they wanted it fixed,” Orr narrates.

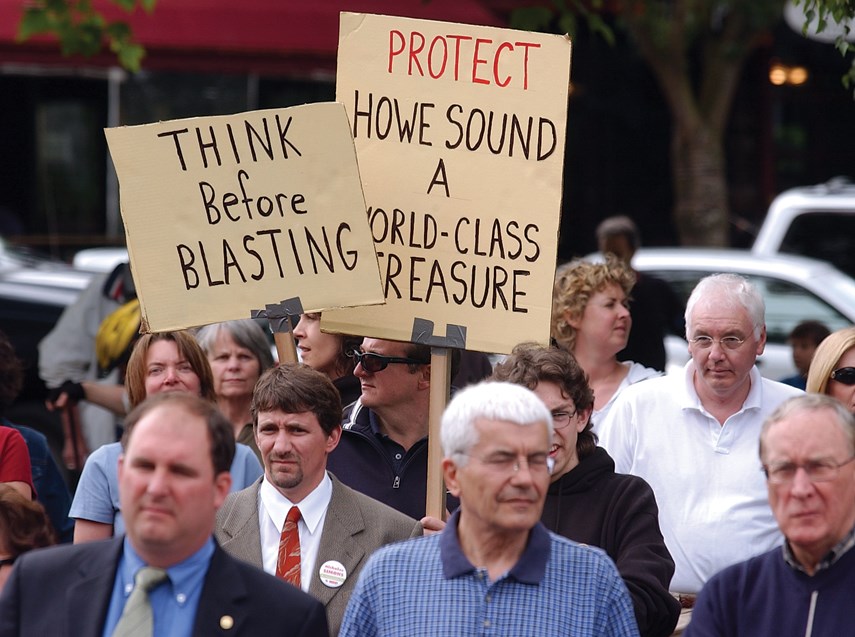

West Â鶹´«Ă˝Ół»residents decried the lack of meaningful dialogue around a plan to route the road through the pristine Eagleridge Bluffs. Despite weathering criticism that their homes also necessitated clearcutting, the protesters occupied the bluffs for 39 days. Orr is there with his camera as the blockade is broken up and one protester attempts to storm the police fence in his wheelchair.

Orr’s camera is also there as the workers who built the highway get a medal and a hearty handshake from Campbell.

Poole, who once employed a young Gordon Campbell for $2.84 an hour at a construction job, gives the credit for the Olympics to his former labourer.

“In my view, they’re Premier Campbell’s Games,” Poole says.

Orr notes that Vancouver’s bid for the Games ramped up around the time Campbell faced charges for impaired driving.

“His political currency was in desperate need of something shiny and bulletproof,” he says in the doc.

Poole wouldn’t see the Olympics. But he did envision a legacy, including the highway and Vancouver’s expanded convention centre.

After being diagnosed with pancreatic cancer Poole underwent radiation and chemotherapy before going back to work.

“They basically give you all you can take without killing you,” Poole tells Orr.

The treatment seemed like a success but the cancer returned. Poole died Oct. 23, 2009.

Discussing the impact of the Games a decade later, Orr is skeptical about a long-term benefit for the city.

“I don’t think there was much of a legacy,” he says. “We got a new highway and we got a $120-million ski jump, that’s handy.”

But when it comes to the three guys behind the games, Orr is sympathetic to their game of “what if?”

“I would like to maintain a cynical perspective on humanity but honestly I think these three guys thought, in their own way, that this would make B.C. a better place.”