Last summer, Fable Diner moved into the Lee Building, which has anchored Broadway and Main for 105 years, and took its place among restaurants that have occupied the space since 1949.

Walk north and you’ll find the mecca of craft breweries that are this century’s incarnation of Brewery Creek; around the turn of the previous century, four neighbourhood breweries gave the area its nickname.

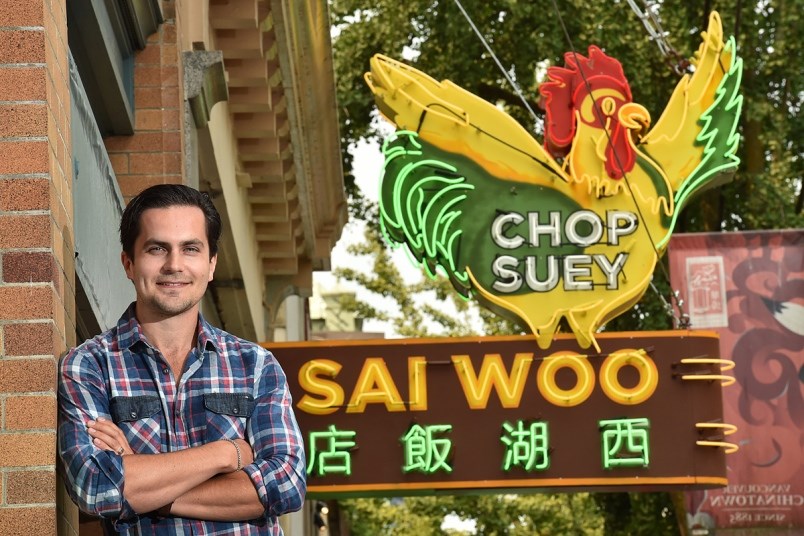

Walk north again and you’ll find Sai Woo in Chinatown, a swanky pan-Asian restaurant and cocktail lounge that borrows its name from the restaurant that was there in the 1920s. You can’t miss the giant neon rooster, another nod to the past, a meticulous recreation of the old Sai Woo Chop Suey sign in the days when Chinatown was bathed in neon.

Love for history and heritage is alive in Vancouver, and increasingly this love is showing up in places where you spend money. Think of something you consumed lately that harkened to the past or boasted being artisan or authentic.

But this love, this business of nostalgia, can be a double-edged sword.

‘Symbolic cannibalism’

Zachary Hyde, a UBC sociology PhD candidate who studies gentrification and urban development, believes a kind of cannibalism is at work.

Hyde, born and raised in Vancouver, remembers Reno’s Restaurant, the Lee Building diner before Fable, as a place to get an affordable plate of food. Reno’s was unassuming, with no-frills greasy spoon fare, but was welcoming to Mount Pleasant’s low-income residents.

“The point is that it wasn’t special or elaborate, but it had a function in the community as a place where anyone could go to get a basic breakfast,” said Hyde.

Then Reno’s closed in 2015, and Fable Diner opened a year later. Gone were Reno’s vinyl booths and the $5 all-day breakfast. Fable continued the nostalgic vibe of a diner with diner food, booths, a bar counter and an open kitchen.

Hyde calls this symbolic cannibalism, a kind of cultural appropriation he recently wrote about in The Mainlander, a local online publication.

“It’s when the surface-level symbols of a particular culture are used for status-seeking purposes,” he said, “but at the same time, excluding the people who made that culture.”

The physical elements of casual diner culture are here — albeit with sleek new furnishings, lights and décor — but Fable serves people who can pay more than the Reno’s crowd. The all-day breakfast is $12.

Blue-collar special

Symbols of blue-collar culture are increasingly used by businesses that aren’t blue-collar. Brick walls, mottled concrete, Edison light bulbs are common in pricey new cafés and clothing boutiques. These elements make businesses feel authentic, as if they’re continuing a neighbourhood’s history. Think of Gastown and Railtown: both are former industrial areas where people now go to spend money on leisure.

Condo marketers, too, are making use of local symbols to make new developments feel authentic and at home in former working-class neighbourhoods.

Developer Rize Alliance hired Rennie Marketing to publicize its Mount Pleasant condo tower, and the results attempt to capture the neighbourhood’s alternative spirit: ads are hand-drawn, the name of the tower is the Independent and a video highlights Mount Pleasant’s “crafted living” of park meet-ups, cool restaurants and characters like florists, fishmongers and skaters.

�鶹��ýӳ��isn’t the only city being transformed in this way. New high-end retail and redevelopment in working-class neighbourhoods of many global cities are making use of existing low-brow symbols to attract newcomers. This makes new businesses and new developments feel organically situated.

But there’s a power struggle between those who can afford to open and eat at pricier restaurants and those who live in a neighbourhood but can’t afford its amenities.

Community outcry

The Carnegie Community Action Project (CCAP), a project of the Downtown Eastside’s Carnegie Community Centre Association, has been outspoken on retail gentrification, the displacement of cheaper businesses by higher end ones, in Vancouver’s low-income neighbourhoods.

“As an argument, a lot of owners are saying they’re moving into these communities because rent is affordable,” said coordinator Lenée Son of CCAP. “But they need to be aware of what kind of community they’re moving into.”

A CCAP report last February labels 156 businesses in the Downtown Eastsisde and Chinatown — “neighbourhoods with long histories of oppression and marginalization,” said Son — as “zones of exclusion”: places low-income people can’t afford, places with strict surveillance, places that cater to rich, outside visitors rather than the local community.

Even if a high-end business claims to be moving into a neighbourhood like Chinatown for its distinct character, it can be damaging, says Son.

“No matter what the intentions are, the fact is, these new businesses are contributing to gentrification, they are contributing to the displacement of marginalized folks.”

In an area home to high levels of drug use, poverty, mental illness, sex work and homelessness, you can buy products such as an $11 16-ounce juice and $138 real mink eyelashes, says the report.

Tragically hip

As Vancouver’s neighbourhoods transform, UBC’s Hyde points to the use of language used in branding, such as calling an area “cool,” “fast-growing,” or “up-and-coming.” Phrases like this imply an area wasn’t cool before and that it had no history.

Fraserhood for example — home to the first Earnest Ice Cream, Italian restaurant Osteria Savio Volpe, Crowbar and a number of new coffee shops — has been recently heralded as a hot new neighbourhood.

But Lory O of the area’s Filipino tofu and dessert shop O! Taho said that she “had to” open in the area, not because it was Fraserhood, but because it was “a Filipino place.” There are Vietnamese and Polish businesses around too.

Marketing, lifestyle media and social media often forget to highlight the humbler communities that called an area home before hip destination eateries and shops move in. The focus is usually on the excitement of unique newcomers, not who gets left out.

“People on welfare were able to afford to eat at places like Reno’s. It was somewhere anyone could grab a bite to eat,” said Hyde. “This isn’t just a matter of old versus new — it’s a matter of economic exclusion and the ability of everyone to participate in public life, regardless of their income.”