It’s a simple story, and yet so difficult for some to comprehend how it could happen in Canada.

Above all, the story is devastating.

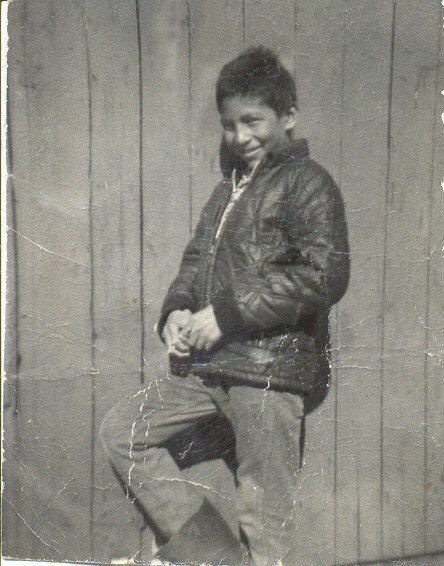

Chanie Wenjack was just nine years old when he was taken from his family and sent to a residential school 600 kilometres away from his home in northern Ontario. Three years later he ran away from the school in an attempt to get back to his home and see his father. He was found frozen to death beside a railroad track. He was 12 years old.

“It’s so heart-wrenching that a young boy was ripped away from his family and endured abuses at the school just for wanting to go back home,” said Brad Baker about the impact of the Chanie Wenjack story. “He did what he could to walk along those railway tracks just to be with his family. He wanted to be with his family. And he didn’t make it.”

Wenjack died in 1966, and 50 years later his story has become the centrepiece of a new campaign to inform all Canadians about the horrors of the government-sponsored residential school system – a system that was created to erase the history and culture of First Nations people and assimilate them into Euro-Canadian culture – and to work towards reconciliation.

Baker is a district principal in North Â鶹´«Ă˝Ół»School District in charge of Indigenous education, safe schools and careers. He is also one of the champions behind a new partnership between the school district and the Gord Downie & Chanie Wenjack Fund (DWF), an organization that aims to “continue the conversation that began with Chanie Wenjack’s residential school story, and to support the reconciliation process through awareness, education, and action.”

On Wednesday more than 40 students from North Vancouver’s Norgate Community Elementary XwemĂ©lch’stn – one of five North Â鶹´«Ă˝Ół»schools involved in the launch of the new partnership – gathered at a monument to victims located near the site of the old St. Paul’s Indian Residential School in central North Â鶹´«Ă˝Ół»to kick off the first annual Secret Path week.

The students, teachers and district administrators listened as survivors Tsnomot, Paitsmuck and Sempulyan described their own experiences in the residential school system, which began in 1880 and continued for more than 100 years until the last school was closed in 1996.

“They took me from my home at six years of age,” Paitsmuck told the students. “At night when we were in our dormitory beds, the little ones would be crying for their moms and dads.”

Those words from survivors are hard to hear, but vitally important to share, said Baker, the son of Tsnomot.

The numbers are impossible to confirm but it is estimated that approximately 150,000 children attended residential schools. Estimates guess that around 6,000 children, like Wenjack, never made it home alive, while countless others were left scarred by physical, psychological, and sexual abuse.   Â

“Every time I hear a story – just talking about it now, I get emotional – every time I hear a story it breaks my heart a little bit to know what our elders who went to those residential schools went through,” said Baker. “It’s almost like my generation has the obligation, and also the opportunity, to be agents of change of the next chapter in Canadian history.”

The partnership with DWF is a step in that direction, said Baker. Norgate, Westview, Carisbrooke and Sherwood Park elementary schools and Windsor Secondary are the five North Â鶹´«Ă˝Ół»schools involved in the initial rollout of the program. The Downie-Wenjack fund is supplying tool kits for classrooms to teach students about Wenjack and the residential schools story and to provide guidance for moving forward with reconciliation.Â

“DWF is so grateful for Legacy School champions like Brad Baker and the North Â鶹´«Ă˝Ół»School District that ensure students are educated about the history and legacy of residential schools,” stated DWF executive director Sarah Midanik in a note to the North Shore News. “Through education and action, we can walk together on this path towards reconciliation.”Â

Gord Downie’s legacy is a driving force behind the project. The late Canadian icon, frontman of the rock band The Tragically Hip, spent his last months alive working on Secret Path, a project that started as 10 poems written by Downie and grew into an album, graphic novel and documentary film about Chanie Wenjack.

Wednesday Oct. 17, the day that students met in North Â鶹´«Ă˝Ół»to hear from survivors, was the one-year anniversary of Gord Downie’s death.

“Through his work and through his struggles and through his death, he has made all of us realize we need to be better Canadians,” said Baker. “It just increased his legacy as a Canadian icon who wanted all of us as Canadians to understand that our history has not always been good. What he said in his final concert in Kingston, he said we were taught to ignore the residential schools and what we’ve done to First Nations for too long, now we need to talk about it. That’s a powerful line.”

With projects like this gaining national attention, we may finally be on the right path, said Baker.

“We still have a long way to go, but I think we’re on a pathway where we will have reconciliation,” he said. “In the big picture, our students want to know about Canada and our history. The more the younger kids hear about the good, the bad, the ugly with Canada’s history, it’s only going to make our country better. We’ll ask them to go home and talk to their parents about it, about what Chanie’s story was, about what the Indian residential school story was, and that just will bring us together and make it a better place than it already is.”

For more information on the Gord Downie & Chanie Wenjack Fund, visit .