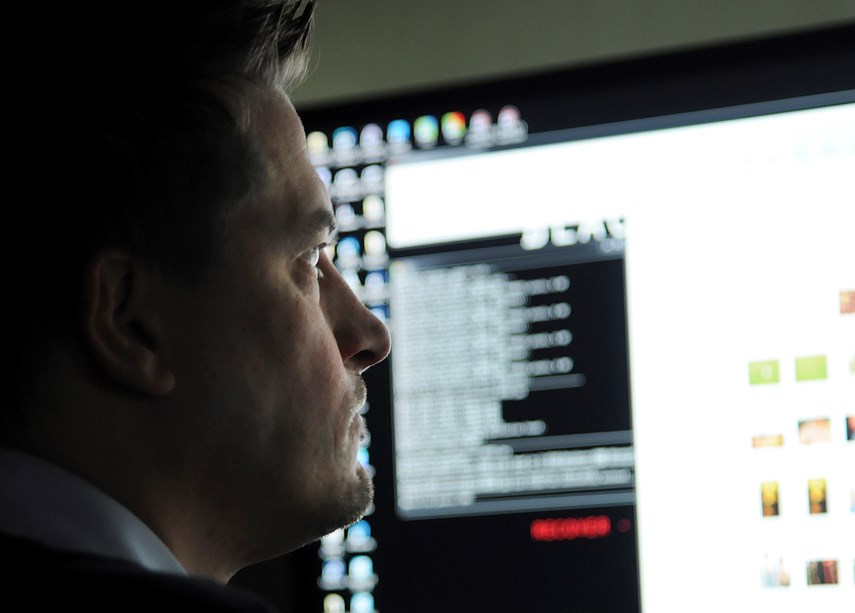

Dave McKay doesn’t see the world in the same way that you or I do.

While we might glance with alarm at a news photo of a North Korean missile test, McKay is more likely to note the pattern of the gas vapours billowing in the wake of the launch and the shape of their trajectories.

He sees where the shadows fall in photographs and hears the background noise of a fan behind a conversation.

As a digital detective, McKay is also keenly aware of the pixels swimming under the surface of images and the invisible fingerprints left on much of what we take as unfiltered truth, even in an era of so-called “fake news.”

McKay, a North Â鶹´«Ă˝Ół»resident, first honed his skills as a forensic video analyst with several Lower Mainland RCMP detachments, including North Vancouver. More recently, he’s taught techniques in analyzing digital clues as head of forensic science and technology at BCIT, as well as examining evidence as a private consultant through his North Â鶹´«Ă˝Ół»company Blackstone Forensics.

Early on, McKay combined an interest in science and problem solving with an aptitude for cinematography that he developed by creating professional snowboard and mountain bike films on the North Shore while he was still in his 20s.

Knowing how video and audio files are created proved useful during his work behind the scenes with the RCMP.

While working with law enforcement, he could also see how digital sleuthing would likely become a growth industry.

In the past, when someone witnessed a car accident or a fight on a street, the first thing they would do is call 911, says McKay. These days “the first thing people are doing is pulling out their phones to record the incident.”

One 'clip' doesn't always give full story

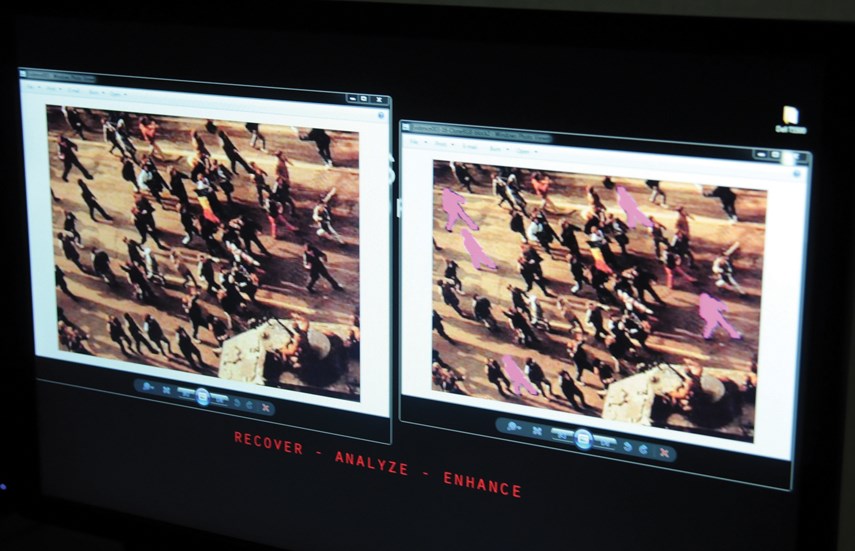

In his unmarked North Â鶹´«Ă˝Ół»office, an advanced video editing system is the key piece of equipment McKay uses to sift through digital clues. A large encrypted video server stores results of his analysis.

There are also some pieces of “legacy equipment” scattered around, just in case – a VHS tape player for instance, and recorders capable of playing back mini audio tapes. “You never know what you’re going to get,” says McKay.

When it comes to video and audio recordings, often one clip won’t give the whole story of what happened. “You have to put it in context too,” says McKay. “What happened before the camera was turned on or after the camera was turned off.”

“Often you have to have multiple sources to depict what actually occurred.”

McKay did just that when he synched separate video and audio clips from the controversial fatal police shooting of teenager Tony Robinson Jr. in Madison, Wis.,Ěý in March of 2015.

McKay calls up a grainy black and white video of a street blanketed in snow. A police officer walks up to a door and disappears inside a house while bursts from a police radio crackle in the background. Suddenly there is the sound of a gunshot. The police officer backs out of the door, his weapon pointed into the house and firing.

A police shooting in the U.S. is reviewed by Blackstone Forensics

In that case, McKay used the flash of the gun and the sound of the gunshots to sync video from the cruiser’s dash cam and audio from a second police car, recreating the work of police analysts at the request of a lawyer for the 19-year-old’s family.

The analysis showed it was “less than a second” between the sound of the first gunshot and when the officer was captured on video backing out of the door. “Part of the controversy in this file was where the police officer said he was when he started discharging his firearm,” says McKay. “He said he was at the top of the stairs inside the house.” But the video analysis showed that was impossible.

The City of Madison later paid $3.5 million to settle a civil lawsuit with the family of the man shot by the police officer.

Easy to alter online or digital information

McKay doesn’t start by looking for anything specific in the videos. His job is to make sure the best information is available to those who will reach conclusions about it. “Most people can look at video and make their own determination about what they’re seeing,” he says.

Working with original videos, photos or recordings is key to digital forensic analysis.

“You don’t want to rely on what someone’s posted on Facebook or Twitter,” says McKay, “Because we don’t know the processing that’s happened to it before it was posted…”

“It can be easy to alter and manipulate some of this information,” says McKay – as anyone who’s used an Instagram filter is aware. “You really have to be careful what you believe when you see things on the internet.”

When looking at an image, McKay first scans for visual clues. “Are the shadows in the right place based on where the sun is supposed to be for that time?”

Far more telling, however, is an examination of the “metadata” – or digital fingerprint – that every recording contains. That will reveal which model of cellphone or camera created it, and whether it has been opened in any kind of editing software.

Further analysis can show if there are parts of an image that have been changed, because an altered area won’t save exactly the same way as the original. Repeating that process hundreds of times through special software will result in those areas popping out visually.

One photo used as a example by forensics instructors shows a group of political protesters in front of a tank in Romania. But after running it through detection software, several of the people in the photograph are revealed as cloned images of the others.

Changing photographs for political reasons is actually not that uncommon, says McKay.

“North Korea and China are known to Photoshop a lot of images,” he says. Iran has also been guilty. A 2008 photo of an Iranian missile test that ran in major U.S. newspapers, for example, included an extra missile cloned into the photo.

By moving the slider, you can see how an image can be manipulated to show, among other things, an extra missile

Ěý

More mundane domestic examples could involve prospective students or employees faking their credentials now that many universities and employers will accept images of documents.

In another infamous case involving scientific research, an image containing the results of a stem cell experiment submitted to an academic journal had its legitimacy questioned. When analysts probed deeper, they found information from a website curiously stamped into the metadata for the photograph. The image width and height also didn’t fit the unaltered dimensions of any camera, further indicating it had been edited. Software eventually revealed that three “cells” in the image had been added to the photograph, in an attempt to show a better result.

“There’s lots of reasons why someone might Photoshop images,” says McKay. “Say they crashed their car and they wanted to make the damage look worse than it was or less than it was.”

Or they may want to hide something they don’t want anyone to see.

Digital world not always as it seems

In one of the criminal cases he worked on with the RCMP, metadata proved key to a case of alleged sexual assault by a taxi driver on a female passenger. “At that point all the cabs in the Lower Mainland had just gotten taxi cameras installed,” says McKay.

Police seized the cab recording. But the images weren’t conclusive. “It looked like it was going to come down to a case of he said/she said.”

But the metadata had another story to tell.

McKay’s analysis detected a regular pattern of images, taken on an automatically timed cycle, until shortly after the alleged assault – when the camera was suddenly prompted to take thousands of images by the driver’s panic button over the next few days.

Drivers knew those images would be given priority, said McKay, and as the image card filled up, they would over-write any previously recorded photos.

“What we realized eventually was that what he was trying to do was erase the images on the card,” said McKay. The driver was eventually convicted, based in part on his post-offence conduct.

That’s one of a relatively small number of cases where McKay knows the results of his work. As an evidence analyst, “you’re provided the least amount of information that you need to know to do the work,” he says. “A lot of times I don’t know who the people are who provided these files. I don’t know what the file is about. A lot of times I never hear, unless I go to court, what the results are.”

Recovery of deleted information is another part of digital forensics.

“The reality is anything you have on your phone or your computer – even if you’ve deleted it – in many cases it’s still recoverable. Even going back years and years and years,” says McKay.

For one BCIT project with his students, McKay bought a refurbished Samsung Galaxy phone from a store. The phone was billed as “factory re-set.”

At first glance, the phone appeared to be blank.

But after its contents were run through a specialized extraction program “we were able to recover hundreds of photos and video and text messages from the previous two users.”

Participants in Facebook and Skype chats, calendar entries, the GPS coordinates of the phone’s location at various points in time were all instantly available.

“This data goes back to 2012,” he says. “I bought the phone in 2015. I didn’t know I was going to find any of it.”

There is speculation the company, Cellebrite – which created the extraction software – was also the mysterious third party which helped the FBI unlock the cellphone of the 2015 San Bernardino shooters, although that has never been confirmed.

From a technical standpoint, deleting information only deletes the pathway the computer – or phone – uses to get to it.

The only way to really get rid of it is to do what the taxi driver did – write other data on top of it, many, many times.

What lies beneath the surface of the digital world isn’t always what it seems. That’s something that’s worth bearing in mind, as we spend more of our lives in cyberspace.

Says McKay, “I never take anything at face value.”