There’s often no words left to describe the pain and grief a parent experiences after losing a child, but luckily Becky Livingston has found a few.

Livingston’s eldest daughter, Rachel, was 15 years old when she was diagnosed with a brain tumour back in 2002.

Not to be deterred by her serious diagnosis, Rachel attempted what many young people spurred on by the conclusion of high school and in possession of an adventurous spirit do when they reach 18 years of age: she flew the coop.

Rachel had always wanted to travel, and took off as a solo backpacker to New Zealand’s green pastures as soon as she could, following the blessing of her doctors and the support of her nervous but always caring parents.

For the next few years, Rachel would come home, work for a bit, and then embark on another adventure in a bid to see just what the wide world had to offer – while she still could.

In addition to New Zealand, Rachel had ample adventures in Australia, Europe, the U.S., Costa Rica and Mexico, all before she was 23.

“You don’t know when you’ve got a brain tumour how long you’ve got to live,” explains Livingston, who was a longtime teacher in West �鶹��ýӳ��and now resides in Nelson, B.C. “I think it was probably about a year after she died that I really hit the very worst of my grief and that’s when I started to realize I have got to change everything.”

Rachel died in 2010, just three weeks shy of the commencement of the �鶹��ýӳ��Winter Olympics, her mom explains.

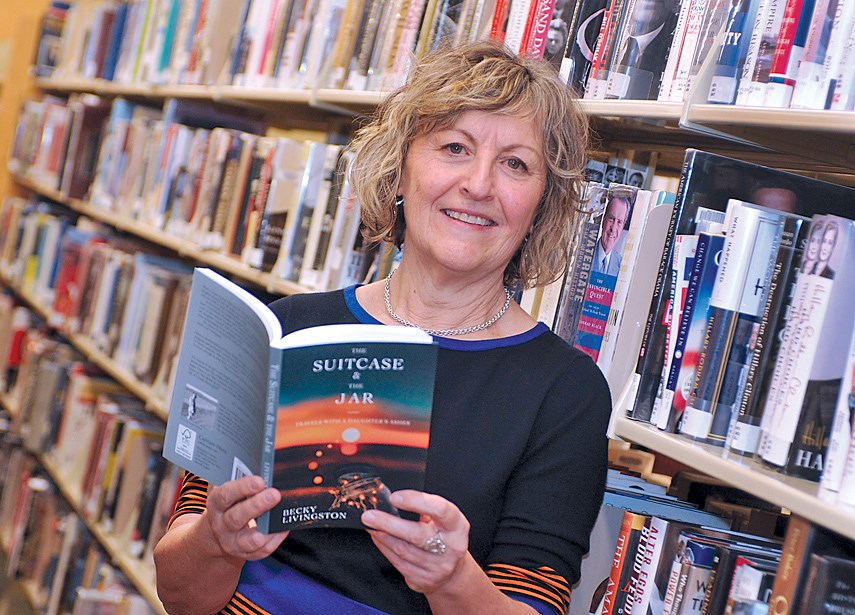

Now Livingston has published her first book, a memoir called The Suitcase and the Jar: Travels with a Daughter's Ashes, which explores what came next.

Livingston found herself in a bad state following her daughter’s passing. An unimaginable fate, her fiancé had actually passed away under similar circumstances some years prior.

“There are no words,” Livingston says when asked how she coped following her daughter’s passing.

As she dealt with her grief, it was decided that helping to fufil Rachel’s dying wish, which was to keep travelling, would be good for Livingston’s well-being in addition to her daughter’s memory.

“She wanted to keep travelling,” she says. “There’s something about travel which is so powerful when it comes to resorting everything in your life. I think it helps you get perspective, you see that grief’s everywhere. Everybody’s dealing with something.”

In 2011, Livingston, then 53, dropped everything. She handed in her notice at work and set off overseas with no agenda or timeline in tow.

For the next 26 months, Livingston, untethered and travelling solo, explored Italy, Spain, Switzerland, Australia, India, England, Ireland and much of North America.

In Livingston’s suitcase, her daughter travelled alongside her.

As Livingston journeyed from corner to corner of the globe she would leave Rachel’s ashes wherever she went.

“I had no idea I was going to be gone that long,” she says.

“I had every intention of coming home and settling down, but I wasn’t ready. I was still leaving Rachel’s ashes, so I just kept going, going, going.”

As Livingston travelled for the next 798 days, she realized that the global scattering of her daughter’s ashes became her own private ritual, a way to restore order following grief’s disordering effect.

Places that she particularly liked – and she thought Rachel might like, such as the California coast – she left more of her ashes there. Places she enjoyed less only received a sprinkling, but either way, Livingston says, he daughter gets to continue her explorations.

“Grief is very much like travel in the sense that you’re very dislocated, you don’t really belong anywhere, and the world falls away. In a way, the travelling was very much a mirror to my grief,” she says. “I’m not sure I understood that until I started to write.”

When Livingston finally returned to Canada she knew, despite her trip’s redemptive qualities, she wasn’t ready to return to work.

But she did know she wanted to write.

She had an idea for one book, but the wise words of a friend who stated that “only you can write this book” steered her in the direction of memoir.

First, she had to learn. “I would say basically I sat for three years and did nothing but write.”

She took her completed work to the �鶹��ýӳ��Manuscript Intensive and worked out the kinks with her mentor, renowned author and educator Betsy Warland, before the book was finally published in September through Caitlin Press, five years after first setting off in her journey to transform grief into peace.

“I don’t think I ever really thought about who’s going to read this. This was very much something I needed to do. It was kind of like the journey ended of moving and it became an internal journey.”

Through her travels and the process of writing her book, Livingston says she learned that it’s possible to find joy again in a world of grief. It’s a message she hopes others who read the book can adopt.

Asked how Rachel would likely respond to her mom’s adventures and endeavours, she says she would say: “‘Way to go, mom. You’re rockin’ it!’”

Livingston is thrilled that in some tiny way, her daughter can do what she always dreamed of — which always was to keep going, keep exploring.

“(Rachel’s) in the sea, and rivers, and the sky, and the sand, and the dirt. She’s everywhere. She’s still travelling.”