In the Dr. Seuss book, Bartholomew and the Oobleck, oobleck is a fictional green substance – “like a sticky slime,” says Keenan Warhurst.

For the Grade 7 student from Lillooet, it's also the stuff of Science Fair dreams.

On Sunday, Keenan won CBC Vancouver’s inaugural Science Fair for his project Oobleck + Helmets = ?.

As a two-time provincial champion Motocross rider, Keenan is used to riding the bumps, jumps and berms in Motocross competition.

Competing in the sport has led to a curiosity about safer equipment.

“I’ve never hit my head, but I’ve definitely had a couple of bad crashes,” he told the Lillooet News. “Last year I broke my leg during a competition in Kamloops.”

His Motocross coach Dave Molenaar has suffered three concussions so he encouraged Keenan’s research into oobleck.

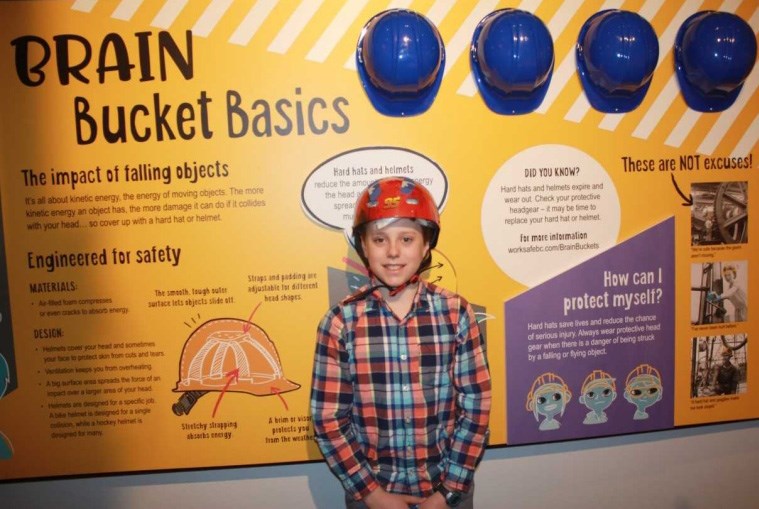

Keenan’s project focuses on whether oobleck has the potential to replace styrofoam in helmets.

“When you apply a lot of force, it acts as a solid,” he explains. “But if you stick your finger into it, it’s a liquid.”

He adds helpfully, “It’s called a non-Newtonian fluid.”

For those of us who don’t know what a non-Newtonian fluid is, oobleck and other pressure-dependent substances such as Silly Putty and quicksand are not liquids like water or oil.

Applying pressure to the Oobleck mixture increases its viscosity (thickness). A quick tap on the surface of oobleck will make it feel hard, because it forces the cornstarch particles together. But dip your hand slowly into the mix, and see what happens - your fingers slide in as easily as through water. That’s because moving slowly gives the cornstarch particles time to move out of the way.

In a series of tests, Keenan has compared oobleck to the expanded polystyrene foam used in bike safety helmets. With Keenan using everything from nails pounded into boards to flexi-force sensors, fiberglass casting material and iron balls and other weights, Oobleck has performed well.

In his most recent experiments, Keenan conducted tests at Vancouver’s Science World to measure how G-force would impact the helmet on top of a dummy’s head when a weight is dropped on that helmet.

He conducted 50 of those drops with a helmet cushioned with oobleck and compared those to weight drops on a typical child’s bike helmet and drops on a bike helmet with no lining.

What were the results? “We found oobleck actually works 30 per cent better than a typical bike helmet,” says Keenan. “I was really surprised about that.”Ěý

Does he know if other students are doing similar research?

“I think I’m pretty much the only one,” he answers. “I’ve heard of other projects on oobleck, but not as something used in helmets.”

Could the day come when children could be wearing Oobleck-lined helmets, rather than a foam ones?

“Maybe” is his cagey reply.

But there is one complication – “The only problem with oobleck is it’s heavier and styrofoam is really light. You can’t make it lighter. If you take the water out, all you have is cornstarch.”

Keenan was one of the province’s bright young minds who showcased their Science Fair projects before an audience of more than 500.

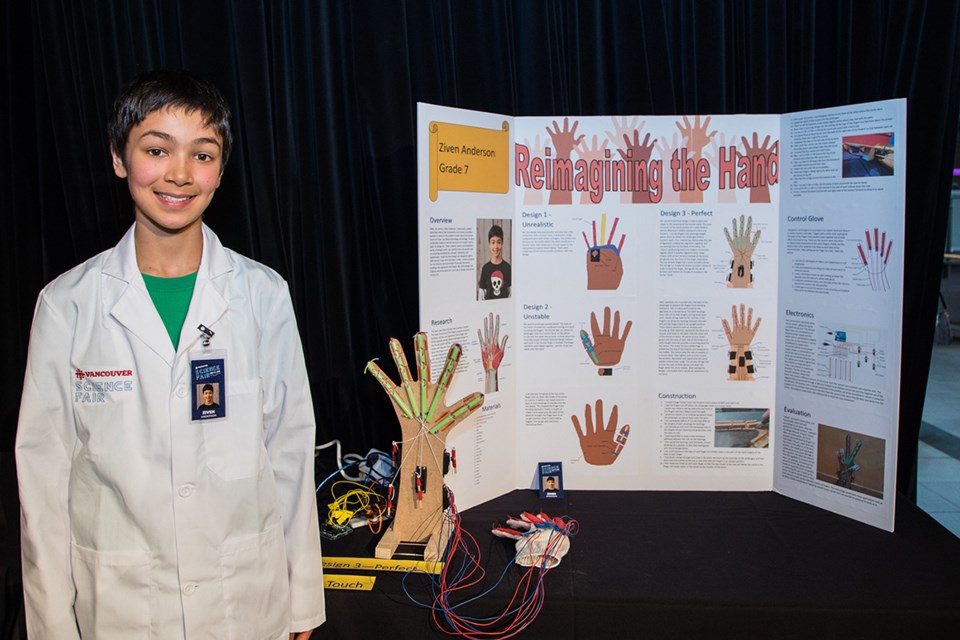

A wide range of topics, based on technology and environment, were featured, including a biogas harvester, modern bridge design, hydraulic power, a robotic human hand, wifi testing, and the wonders of zooplankton

“I was overwhelmed by the caliber and talent of the students at our first CBC Â鶹´«Ă˝Ół»Science Fair,” says Johanna Wagstaffe, CBC Vancouver’s senior meteorologist and seismology expert and science fair judge. “How inspiring to see the curiosity and passion that these young scientists have for STEM.

Â鶹´«Ă˝Ół»Grade 7 student Ziven Anderson of Madrona School placed second for fusing technology and human biology to replicate a human hand. He was able to make a gloved hand that could control a robotic hand.

Keenan's grand prize was a special 3D printed trophy by local company Tinkerine, a $750 Best Buy gift card, and a spot in one of SFU’s Science AL!VE science camps.

At this point, Keenan is unsure about pursuing his experiments into a fourth year.

“The physics is getting really complicated and my mom is not really good at physics. Me and my mom have to put some thought into it.”

Unless he can find a tutor to help him move on to another, more complex phase, it’s possible this may be it for his Oobleck research.

However, this budding scientist shouldn’t have a problem moving on to another intriguing question that piques his curiosity.

“I come from a family where my mom (Dr. Nancy Humber) likes science and my sisters have all done science fair projects,” says Keenan.

In addition to his mom, Keenan has received support and encouragement from Science World, “which let me do my drops before it opened and got busy;” Science World science facilitator Kat Kelly; and former Lillooet teacher Lynn Albertson, who has mentored many young local scientists and “obviously always helped,” (Keenan’s words.)

Asked the proverbial question, “What do you want to be when you grow up?” there is a long pause. He is, after all, 12 years old.

“I would like to do something related to science, or math but I haven’t given it much thought,” he replies. “Science is big fun and it’s definitely a fun way to put your ideas to work.”

Ěý

This story has been edited from to include details about the project and Keenan's science fair win.

Ěý

Ěý

Ěý