There’s a lot of information about COVID infections in the Lower Mainland being flushed down the toilet.

Since last year, Metro Â鶹´«Ã½Ó³»and B.C.’s Centre for Disease Control have been partnering on a project to .

“About half of COVID-19 cases will shed the virus in their feces,” said Natalie Prystajecky, one of B.C.’s Centre for Disease Control’s lead researchers on the project. “So it gives you an opportunity to sort of understand what's happening at the community scale. So instead of testing every person, you can get an entire community from a single wastewater sample.”

Currently information from the project is being used to supplement what is already known about COVID-19 rates in Metro Vancouver. “We consider it to be one of many tools in the toolbox,” said Prystajecky.

Testing for COVID is done once a week at the region’s five sewage treatment plants, taking a composite sample made up of hourly readings for a period of 24 hours.

Sewage concentrations reflect case counts

So far, the scoop from the poop has matched what health authorities have seen in positive case reports from various Lower Mainland communities: the amount of virus detected in sewage tends to reflect infection rates in the community.

That’s good news, said Prystajecky.

It would have been concerning if that wasn’t happening – if the amount of virus detected in sewage seemed far higher than the number of cases being reported, it could have indicated cases that weren’t being detected, for instance.

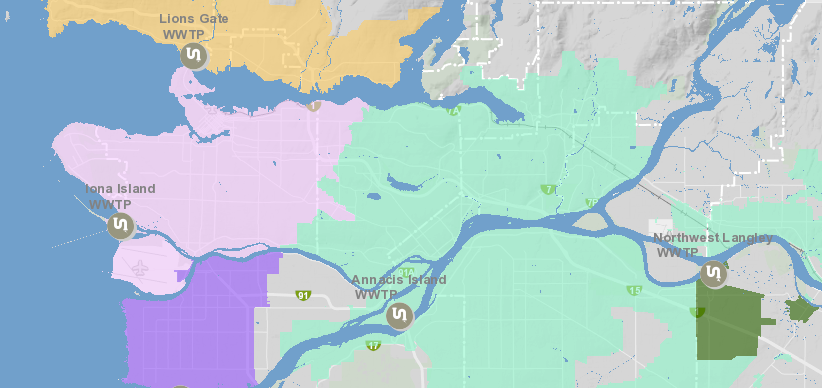

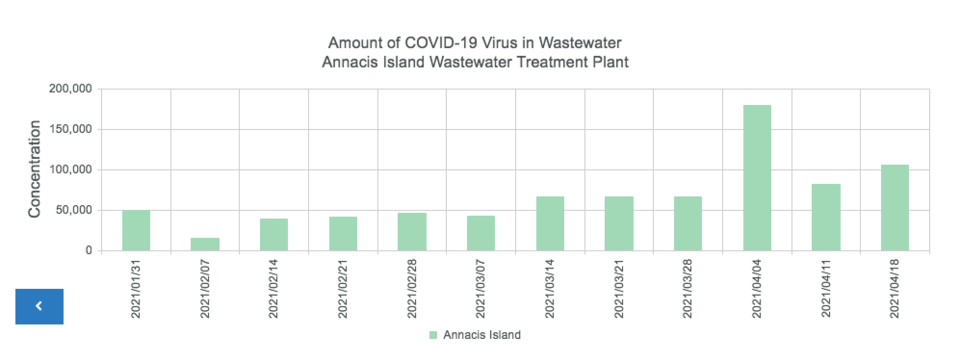

Graphs showing the levels of COVID virus in sewage over time at the region’s wastewater plants can be viewed on .

Not surprisingly, the graphs show the Annacis Island sewage treatment plant – which serves over one million people in 14 municipalities including a large part of the hard-hit Fraser Health area – as having the largest concentration of COVID detected in sewage samples. So far, the largest concentration of COVID registered at just under 180,000 units per litre of untreated sewage in a sample taken April 4. The most recent sample there showed about 106,000 units of the virus.

A bar graph shows concentrations of COVID in sewage entering the Annacis Island Wastewater Treatment Plant. | Metro Vancouver

A bar graph shows concentrations of COVID in sewage entering the Annacis Island Wastewater Treatment Plant. | Metro Vancouver

Iona island, another of the largest treatment plants which handles sewage from about 600,000 residents of Vancouver, Richmond and Burnaby also registered its highest COVID concentration in a sample on April 4 at just under 78,000 units of the virus per litre.

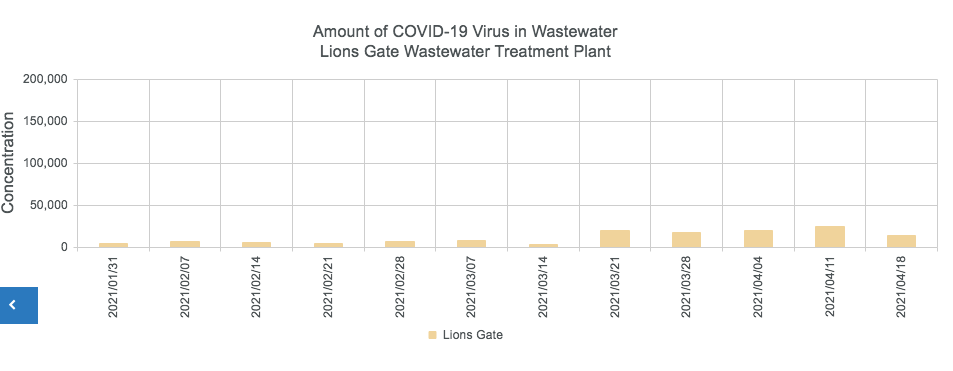

Lions Gate treatment plant shows highest readings in April

Numbers from North Shore sewage treated at the Lions Gate sewage treatment plant are much smaller. The plant which serves 180,000 residents of the North Shore, showed its highest reading – over just under 25,000 units of the virus in a litre of water – on April 11. The most recent sample, taken April 18, showed a drop to around 15,000 units of COVID in a litre of water.

A bar graph shows concentrations of COVID in sewage entering the Lions Gate Wastewater Treatment Plant. | Metro Vancouver

A bar graph shows concentrations of COVID in sewage entering the Lions Gate Wastewater Treatment Plant. | Metro Vancouver

Prystajecky said it’s not possible to directly compare results between the sewage plants directly, because they serve very different sized populations and have wastewater from different types of sources running through them.

“So from that perspective, it's important more important to look at trends over time within one plant than to look at trends between plants,” she said.

On the North Shore, results barely show up until the “second wave” of the pandemic last fall, when relatively small amounts of COVID – around 5,000 to 7,000 units per litre - started to be detected in sewage. Consistent with rising case counts – those results jumped suddenly in the latter part of March to around 20,000 units of COVID per litre.

Similar patterns are evident in results from other sewage plants around Metro Â鶹´«Ã½Ó³»– with concentrations of sewage rising to their highest levels in March and April.

There are still unknowns, said Prystajecky, such as whether variant strains of the COVID-19, which now make up about 75 per cent of cases, are shed the same way in sewage.

In future, similar scans of wastewater could be used to measure other phenomena like antibiotic resistant super bugs, said Prystajecky.