As a rookie, Brock Boeser was a breath of fresh air for Canucks fans.

He announced his presence in a major way in his very first game, by jumping on a Bo Horvat rebound off a, frankly, brilliant assist by Sven Baertschi. in his 9-game stint at the end of the 2016-17 season, providing a jolt of excitement for a fanbase desperate for something to look forward to.

Boeser immediately made good on that potential, erupting for 29 goals in just 62 games, a season that saw him sent to the All-Star Game, win the Accuracy Shooting competition, and only finished as runner-up to the Calder Trophy because of a freak back injury sustained when hit into an open bench door that caused him to miss over a month near the end of the season.

It was a phenomenal season, a 38-goal pace over 82 games that announced Boeser as one of the next generation of great goalscorers.

Keep in mind, the Canucks had just two 30-goal seasons in the six years prior to Boeser’s rookie year: Radim Vrbata score 31 goals in the 2014-15 season and Daniel Sedin just reached 30 in 2011-12. It thrilled Canucks fans that the team had found a sniper that not only would be a regular 30-goal threat but might even score 40+ goals.

Instead, Boeser’s goalscoring fell off a bit in his second season, from 29 to 26 goals in 7 more games. It was a concern, but a mild one. He still scored at a 31-goal pace over an 82-game season, so it was merely a reason to temper expectations.

This past season, however, Boeser’s goalscoring fell off a cliff. He managed just 16 goals in 57 games, a 23-goal pace. That’s straying away from first-line sniper towards decent second-line winger.

To his credit, Boeser has grown other elements of his game, improving his defensive play and growing stronger to win puck battles down low and in front of the net.

“When you’re not scoring goals, you’ve got to figure out ways to help the team any way you can,” said Boeser after the season ended. “I felt [this season] taught me what I need to do when you’re not scoring goals and the little things you can do to help the team out.”

While it’s important for Boeser to continue contributing in all aspects of the game, it’s also important that he doesn’t just do the little things, but a few of the big things too. In order to continue improving next season, the Canucks need Boeser to start putting the puck in the net with more regularity.

Shooting percentage going for a dip

To figure out what went wrong for Boeser this past season, we have to look at what changed. Let’s start with the obvious: shooting percentage.

In his nine-game audition in 2016-17, Boeser scored on 16% of his 25 shots, which seemed like it was too high to continue in his actual rookie season. Instead, Boeser managed to carry a 16.2% shooting percentage through 2017-18. It’s not unheard of for an NHL player to maintain a shooting percentage that high, but it would rank Boeser among the best snipers in the game.

The best career shooting percentage among active players belongs to Steven Stamkos at 16.89%, followed by Leon Draisaitl at 16.85%. They’re the only two players above 16%.

Boeser couldn’t maintain those heights, falling to 12.44% in 2018-19, which could be seen as normal regression to the mean. He fell even farther this past season to 9.5%, which is a little below league average for forwards.

That seems concerning. Shooting percentages fluctuate from year to year for even the best players in the NHL, affected by luck, teammates, and opposition, but it’s still surprising to see Boeser’s shooting percentage dip that low.

Before discussing what might be causing that dip or other reasons Boeser’s goalscoring has fallen off, let’s break his shooting percentage down a little bit further by game state: 5-on-5 and the power play.

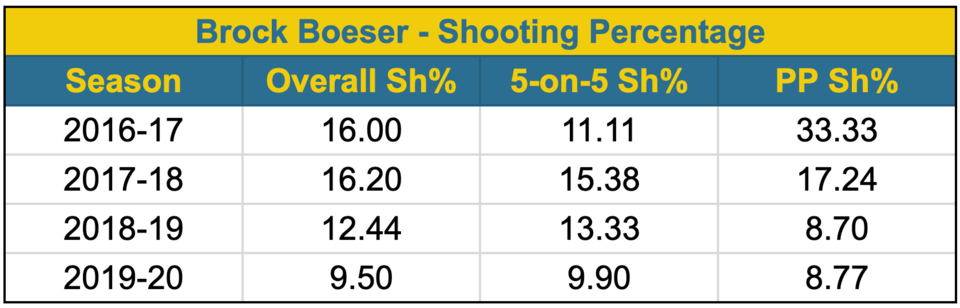

Brock Boeser's shooting percentage by season and situation. Data via NaturalStatTrick.com

Brock Boeser's shooting percentage by season and situation. Data via NaturalStatTrick.comBoeser saw a significant drop in shooting percentage on the power play from 2017-18 to 2018-19, but that shooting percentage then stayed pretty much the same in 2019-20.

One possible cause for that significant a drop is who was feeding him the puck in 2017-18: Daniel and Henrik Sedin. The twins used Boeser as their primary shooter on the power play — he led the Canucks with 58 shots on goal on the power play — and gave him some pretty sweet setups.

Then the Sedins retired. Boeser still led the Canucks in shots on goal on the power play with 69, but he was no longer benefiting from that twin magic known as Sedinery. The power play started to shift more towards setting up Elias Pettersson for one-timers rather than giving Boeser open looks to use his wrist shot.

In 2019-20, Pettersson overtook Boeser for the most shots on the power play and Boeser was frequently moved from the left side of the first unit.

The Sedins might explain some of that shooting percentage collapse on the power play, but what’s intriguing is that he didn’t see as calamitous a drop at 5-on-5 in his sophomore season. It dropped more significantly in 2019-20, however.

Location, location, location

One theory that frequently crops up in fan discussions about Boeser is that his shot just hasn’t been the same since his rookie season. While his back injury caught most of the attention, Boeser also suffered a wrist injury in his rookie year. The injury was to the same wrist that required surgery during his final year at the University of North Dakota, but only required injections and immobilization for a month at that time.

Since then, Boeser has kept his wrist taped up, but he hasn’t seemed to have any issues with it in battles along the boards or in front of the net. According to Boeser, it’s less about the quality of his shot and more to do with how many shots he takes and where on the ice he’s taking them.

“Personally, I don’t think I’ve been shooting the puck as much and getting the looks that I got maybe earlier in my career,” said Boeser. “I definitely think I can continue to work on my shot and find ways to get to those areas to get those shots off.”

If we start with 5-on-5, Boeser isn’t actually taking fewer shots. In terms of shot rate, he averaged 7.95 shots per hour at 5-on-5, right in line with his previous two season. So, let’s take a look at shot location and see what might have changed.

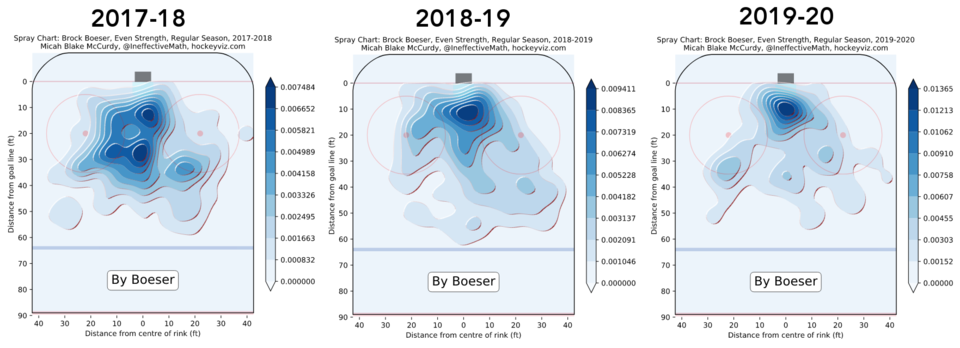

Brock Boeser's even-strength shot locations via HockeyViz.com

Brock Boeser's even-strength shot locations via HockeyViz.comIn these heatmaps from , we can see where the majority of Boeser’s shots came from at even-strength. There’s a distinct move closer to the goal from his rookie year to last season. In most cases, that would be a good thing: those are prime scoring chance areas directly in front of the net, indicative of Boeser getting to the crease more frequently.

What’s really striking, however, is that area between the hashmarks. In his rookie season, Boeser got a ton of chances from between the hashmarks, a great opportunity for him to rifle a wristshot. That’s a highly-visual scoring area too: wristshots from between the hashmarks to beat a goaltender cleanly look stunning and really cement a reputation as a sniper.

Unsurprisingly, that’s where a lot of his goals came from at even strength in 2017-18.

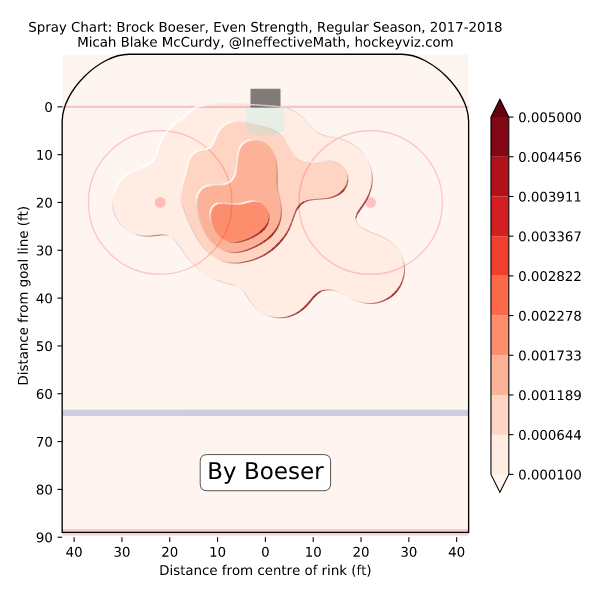

Brock Boeser's 2017-18 even-strength goal-scoring heatmap via HockeyViz.com

Brock Boeser's 2017-18 even-strength goal-scoring heatmap via HockeyViz.comIn his sophomore season, Boeser still had quite a few chances from that area of the ice, but those chances grew far more slim in the 2019-20 season. Most of his shots came from on top of the crease, with a couple hot spots near the top of the left and right faceoff circles. He just didn’t get those opportunities to use his wrist shot from between the hashmarks like he did in previous years.

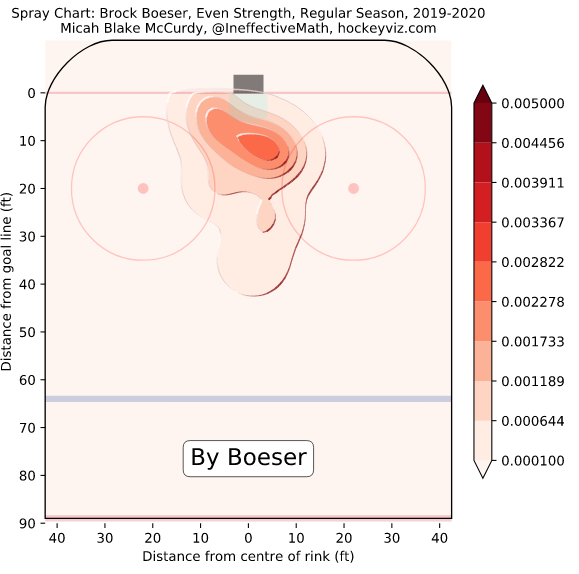

As a result, most of his goals at even-strength in 2019-20 came from a lot closer to the net.

Brock Boeser's 2019-20 even-strength goal-scoring heatmap via HockeyViz.com

Brock Boeser's 2019-20 even-strength goal-scoring heatmap via HockeyViz.comYou could see that as Boeser evolving his game and finding other ways to score, but he also scored a lot fewer goals. He spent a lot more time battling in front of the net than finding empty ice in the slot. It really seems like Boeser needs to find ways to create more scoring chances from between the circles.

The problem is that is easier said than done. Teams are aware of the threat of Boeser’s shot and, in any case, will actively look to prevent chances from that area of the ice no matter who their opponent is.

That’s reflected in another element of Boeser’s shooting that changed over the past few seasons.

Wristers, snappers, and clappers

What’s becoming clear is that Boeser hasn’t stopped shooting the puck. His overall shot rate from 2019-20 is right in line with his previous seasons. What has changed significantly, however, are the types of shots that he’s getting.

The NHL tracks seven different shot types, including backhands, tips, deflections, and wraparounds. Let’s break Boeser’s shots down by his three most common shot types: wrist shots, snapshots, and slap shots.

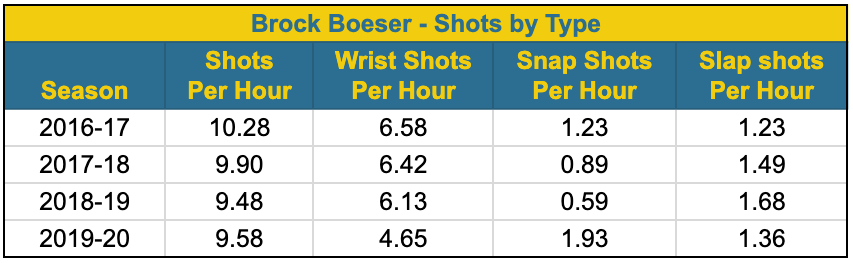

Brock Boeser's shots by type. Data via NHL.com

Brock Boeser's shots by type. Data via NHL.comWe don’t see a huge change in the number of slap shots Boeser took — slightly fewer than his previous couple of seasons, but not overly significant. What we do see is a major change in the number of wrist shots and snapshots.

Boeser averaged around one-and-a-half fewer wrist shots per hour in 2019-20 than he did in his previous season. Meanwhile, his snap shots went up by 1.34. What might explain that major shift in shot types?

One explanation is that snapshots take less time than wrist shots. A snapshot has a much quicker release than a wrist shot, making it a more popular choice when you don’t have a lot of time to shoot or you want to catch a goaltender off-guard. A wrist shot, on the other hand, is generally more powerful and accurate than a snapshot, but tougher to get off in traffic.

If Boeser is being checked more closely by opposing teams, it would follow that he would end up taking more snapshots.

It’s easy to see why that might be a problem. Heading into this season, — his 18.25% shooting percentage was bettered only by Auston Matthews. His shooting percentage on snapshots, on the other hand, was a below-average 7.14%.

His exceptionally high shooting percentage on wrist shots through his sophomore season, incidentally, would seemingly shoot down the theory that his rookie wrist injury affected his shot adversely.

Being forced to take more snapshots, a significantly worse shot for Boeser, would seemingly explain a big drop in goals. Only, this past season it didn’t go that way. In fact, his shooting percentages essentially reversed: he scored on just 8.54% of his wrist shots, but 14.71% of his snapshots.

In other words, it appeared that Boeser improved his snapshot, while his wrist shot got worse.

Still, the theory that pressure from opposition forced Boeser to shorten the time of his release holds water. Perhaps in addition to taking fewer wrist shots, the wrist shots that he did take were more rushed, with less time to pick a corner and beat a goaltender cleanly. That might explain some of the drop in shooting percentage, along with fewer shots from a prime location like between the hashmarks.

There’s one other area we can look at: the power play.

Power play shifts

As mentioned previously, a big part of Boeser’s success on the power play in his rookie season came from playing with the two best playmakers in Canucks’ history: the Sedins. From his rookie to his sophomore season, Boeser’s power play goals were essentially cut in half and that continued in the 2019-20 season.

Boeser averaged 17.94 shots per hour at 5-on-4 in his rookie season and 13.66 in 2019-20. That still led the first power play unit, but only just barely: Pettersson averaged 13.53 shots per hour and Bo Horvat was right behind with 11.35 shots per hour.

In other words, he was the primary shooter on the power play in his rookie year, while the first power play unit spread the shots around a lot more this past season.

The hope was with Quinn Hughes on the point as the quarterback and two shooting threats on either side in Boeser and Pettersson, that the Canucks power play would feast by focussing on setting up those two shooters. That’s not how the season played out. While the power play was successful overall, finishing fourth in the NHL in power play percentage and first in goal differential, it didn’t succeed based on the dual scoring threats at the faceoff circles.

Instead, Bo Horvat and J.T. Miller led the Canucks in power play goals. The first unit created chances for Horvat in the slot and around the net, while Miller frequently played along the boards in place of Boeser, who shifted into the middle or down low, depending on the setup.

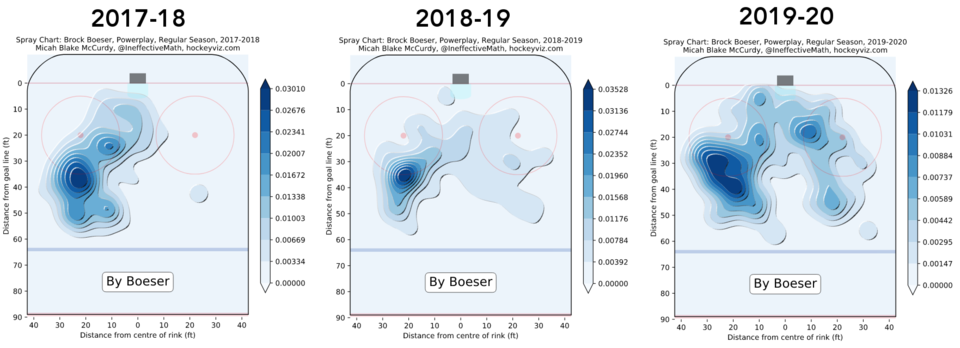

You can see the effect the shifting power play setups had on where Boeser’s shots came from on the power play.

Brock Boeser's power play shot locations via HockeyViz.com

Brock Boeser's power play shot locations via HockeyViz.comBoeser’s power play shots primarily came from the top of the left faceoff circle, where he would hammer away from Alex Ovechkin’s favourite spot on the ice. There was also a clear area where Boeser would move closer to the net to finish off plays, but almost entirely from the left side of the ice.

In 2018-19, Boeser’s shots started to come from a larger area, but the majority of them came from an even more focussed spot on the top of the left faceoff circle. One explanation for why his power play goals dropped is that he didn’t get as many shots from closer to the net like he did in his rookie year.

Then, in 2019-20, Boeser was all over the place. He still took an above-average number of shots from the top of the left faceoff circle, but his shots really reflect the many different roles he played on the power play.

Meanwhile, Boeser didn’t score a single power play goal from the top of the left faceoff circle all season. Of his five power play goals, three came from inside the right faceoff circle and the other two came from down low on the left side.

The power play is no longer built around Boeser’s wrist shot from the left faceoff circle, which is ultimately a good thing. A more diverse power play is more difficult for penalty killers to stop.

So, what’s changed?

Let me explain. No, there’s too much. .

What has changed for Boeser?

- His shooting percentage took a dive on the power play after his rookie year and dropped this past season at even-strength.

- While he’s shooting the puck at around the same rate overall, he’s getting fewer shots on the power play.

- His shots at even-strength are no longer coming from between the hashmarks, where he could pick his spot with a wrist shot.

- He’s getting fewer wrist shots and more snapshots, likely because opponents are giving him less time with the puck.

- His shooting percentage with his wrist shot dropped this past season, possibly for the same reason he took more snapshots — less time to shoot.

- And finally, he was moved all over the place on the power play, as the first unit stopped focusing on setting up his wrist shot from the left side.

Does that answer every reason why Boeser’s goals went from 29 in his rookie year to just 16 this past season? Perhaps not, but it hopefully provides a clearer picture of the issue.

One element that isn’t covered here is confidence. That’s an intangible aspect to goalscoring that has a very tangible effect. A player that is confident in their shot takes chances with it. The puck stays on their stick for less time, as they release the puck more quickly, confident it will hit the back of the net.

A player that isn’t confident might double-clutch when given a scoring chance, second-guessing where or how they want to shoot the puck. In that moment, a window to score can close, whether it’s a goaltender sliding across to take away more of the net or a defender getting a stick in a shooting lane and forcing a lower percentage shot.

Oftentimes, confidence is influenced by luck and vice versa. A player that gets a lucky bounce gets a good feeling about their shot, while a confident player taking more chances creates more opportunities for luck to go their way. A series of bad bounces or unlucky breaks can have the opposite effect, making a player believe that the puck will never go in, which can make a player stop shooting for the top corner and instead just try to hit the net and instead wind up putting the puck in the goaltender’s logo.

It’s just human nature to see a pattern in what may just be a series of unrelated good or bad fortune and that psychological aspect of the game can help or hinder a sniper.

Boeser’s shooting percentage dip can be partially explained by getting fewer wrist shots from a great location on the ice, but part of it could just be bad luck, which in turn affected his confidence. It’s up to Boeser to fix both issues: finding ways to get to prime scoring areas to use his best shot and having the confidence to finish when he does get those chances.

.JPG;w=120;h=80;mode=crop)

.JPG;w=120;h=80;mode=crop)