After a disappointing debut season for the Canucks that was hampered, then ended, by a wrist injury, Erik Gudbranson has a lot to prove when October comes around. There’s a reason Jim Benning last month.

Gudbranson lasted just 30 games last season before a surgery to repair a torn ligament ended his season in December. In those 30 games, he didn’t quite look like the top-four defenceman the Canucks were hoping he would be when they traded Jared McCann and the 33rd overall pick in 2016 for him.

He and Ben Hutton struggled to find chemistry as a pairing, with that seemed to place the blame entirely on Hutton: “He has less than 100 games and it takes 300 to learn to defend well.”

Gudbranson has more than 300 games under his belt, but still struggled with defending well. His corsi percentage was better than just Luca Sbisa among Canucks’ defencemen and he was on the ice for the highest rate of goals against at even-strength: 3.10 per hour. Just three defencemen who played at least 500 minutes at 5-on-5 were on the ice for a higher rate of goals against: Matt Tennyson, Travis Hamonic, and Tyson Barrie.

To be fair to Gudbranson, part of that had to be bad luck. The save percentage of Canucks’ goaltenders with Gudbranson on the ice was just .899, the eighth lowest among NHL defencemen with 500+ minutes at 5-on-5. Considering that , you can’t really blame Gudbranson for that.

Where Gudbranson did struggle last season was in getting the puck out of the defensive zone. Using data, I previously showed that Gudbranson was the worst defenceman on the Canucks at . This was readily apparent from the eye test: Gudbranson frequently failed to move the puck up ice with either a pass or his skating and it led to long shifts trapped in the defensive zone.

But Gudbranson does have one clear strength: preventing the puck from entering the defensive zone in the first place.

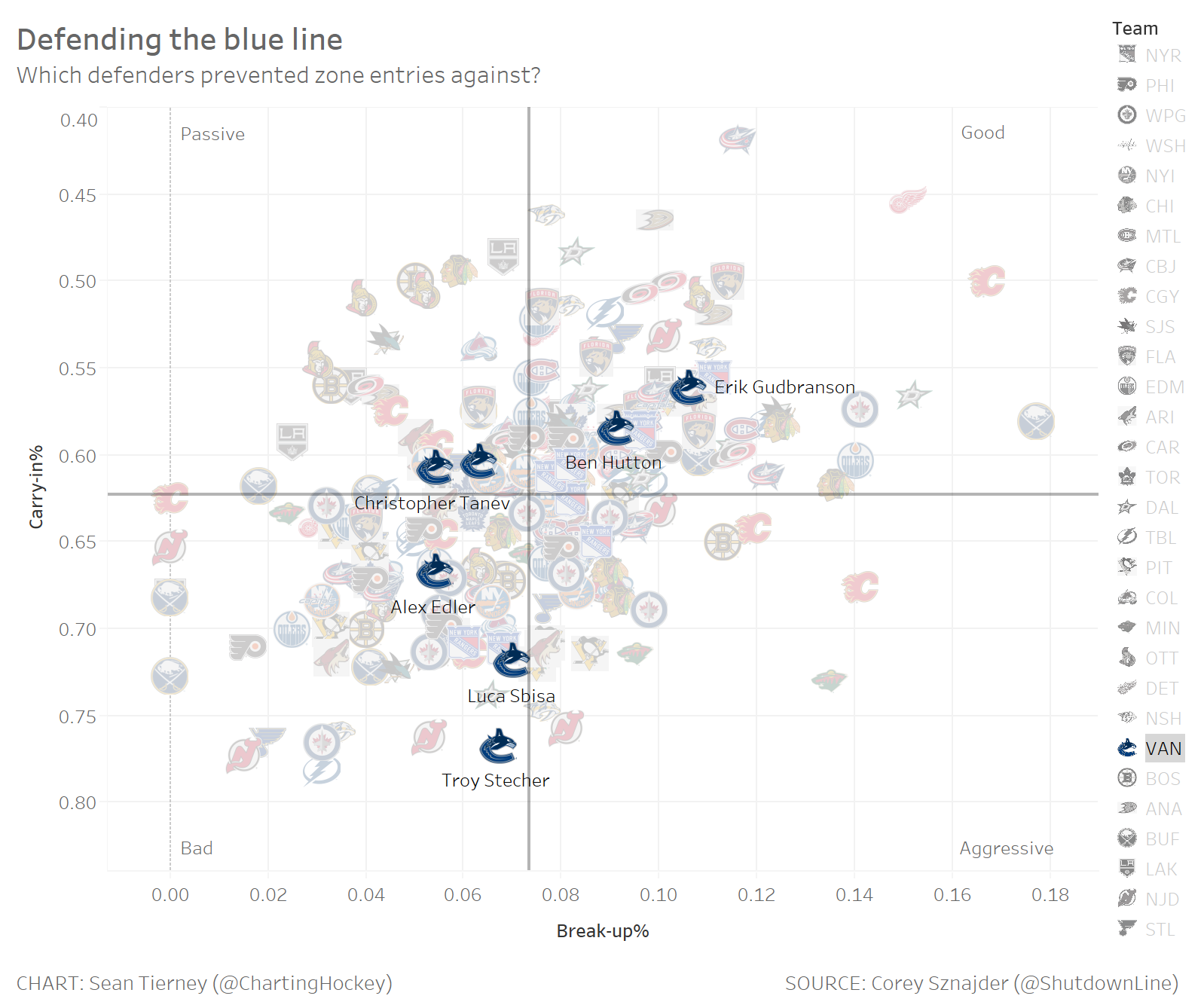

Sean Tierney took Sznajder’s data (which now has a larger sample size than what was used in my previous article) and looked at how NHL teams perform when it comes to preventing zone entries. You can , but here is where the Canucks’ defencemen land on the chart.

��

The x-axis (horizontal) is break-up percentage, as in what percentage of zone entries against were broken up by the player. The y-axis is carry-in percentage, as in the percentage of zone entry attempts that are successfully carried in by the opponents. The higher you are on the chart, the lower the percentage of successful carry-in attempts against. The farther right, the higher the percentage of successful break-ups.

The Canuck ranked highest by both measures: Erik Gudbranson.

For all of Gudbranson’s struggles getting the puck out of the zone, he allowed the lowest percentage of carry-ins by opponents and aggressively broke up zone entries. Closing the gap on zone entries appears to be a legitimate strength of his game. Other defencemen near him on the chart include John Carlson, Brooks Orpik, and Kevin Connauton.

Why does this matter? It has been shown that than from other entries. Therefore, the better your defence can be at preventing these types of controlled entries, the better. And if you can break up a zone entry and turn the puck the other way, all the better.

As for the rest of the Canucks defence, Ben Hutton shows well, finishing above average in both measures. Chris Tanev isn’t aggressive with his break-ups, but still allows a below average number of carry-ins. Appearing right next to him with the name not visible is Philip Larsen.

Alex Edler is below average in both measures, but the really worrying one is Troy Stecher. He has a slightly below-average rate of break-ups, but also has one of the highest carry-in rates in the NHL. Teams had no issues skating the puck in on his side of the ice.

To be fair, his statistics come from a smaller sample size than the other Canucks’ defencemen, as the random sample of games that Sznajder tracked for the Canucks included almost all of the games that Stecher missed last season. Also, he was the Canucks’ best defenceman on zone exits, so he somewhat makes up for this deficiency.

As a whole, the Canucks’ defence of the blue line definitely needs improvement. Is this a matter of personnel or coaching? found that zone entry defence is a repeatable skill on an individual level, but also says, “There may also be team/system impacts that are difficult to separate out from the individual contribution.”

Hopefully, Stecher’s poor results here are a result of a small sample or from being a rookie and that he’ll improve in his second season. Additionally, the Canucks can hopefully make adjustments to their system to improve their blue-line protection.

As for Gudbranson, his zone exits might improve with a healed wrist. Otherwise, he’ll need a defence partner that can handle the bulk of the exits.