Ā鶹“«Ć½Ó³»Canucks general manager Jim Benning believes that Oliver Ekman-Larsson can be the team’s number one defenceman.

That might be a little optimistic. Ekman-Larsson wasn’t even the Coyotes’ number one defenceman last season, finishing third in average ice time behind Jakob Chychrun and Alex Goligoski. Still, the Canucks have to hope that Ekman-Larsson can at least be a quality top-four defenceman for the foreseeable future. He better be; after all, he’s going to have a $7.26 million cap hit for the next six seasons.

There are some obvious things to like about Ekman-Larsson. He has consistently tallied 40+ points per season in his career, including last season when he was on-pace for 43 points in a full 82-game season. He’s played big minutes throughout his career and received Norris votes as recently as the 2018-19 season.

At the very least, Ekman-Larsson should be an upgrade on the Los Angeles Kings-bound Alex Edler. Right?

This is where analytics raise a red flag.

The numbers are unkind to Ekman-Larsson or vice versa

It’s likely well-known to Canucks fans at this point that analytics aren’t exactly high on Ekman-Larsson over the past few seasons.

For instance, Ekman-Larsson’s corsi percentage — the ratio of shot attempts for and against when he was on the ice at 5-on-5 — was 47.91%, which was fifth among regular Arizona Coyotes defencemen. At 5-on-5, the Coyotes were out-scored by 14 goals with Ekman-Larsson on the ice, worst on the team.

That doesn’t sound great, but some might argue those numbers are missing context. Perhaps he was out-shot and out-scored because he was used primarily in the defensive zone against tough competition.

Well, not exactly. Ekman-Larsson did start more shifts in the defensive zone than in the offensive zone, but just barely. Both Jason Demers and Niklas Hjalmarsson started a higher percentage of their shifts in the defensive zone for the Coyotes and got much better results. And Chychrun and Goligoski played against top forward lines far more than Ekman-Larsson, who faced tough competition less than league average.

Charts are no more kind than the numbers

Even if Ekman-Larsson’s context had illustrated a player in tough situations, there are still unambiguous facts to deal with.

It is a fact that Oliver Ekman-Larsson was on the ice for 674 shot attempts against at 5-on-5 last season and 620 shot attempts for. It is a fact that Ekman-Larsson was on the ice for 156 high-danger chances against, as defined by Natural Stat Trick, and 100 high-danger chances for at 5-on-5.

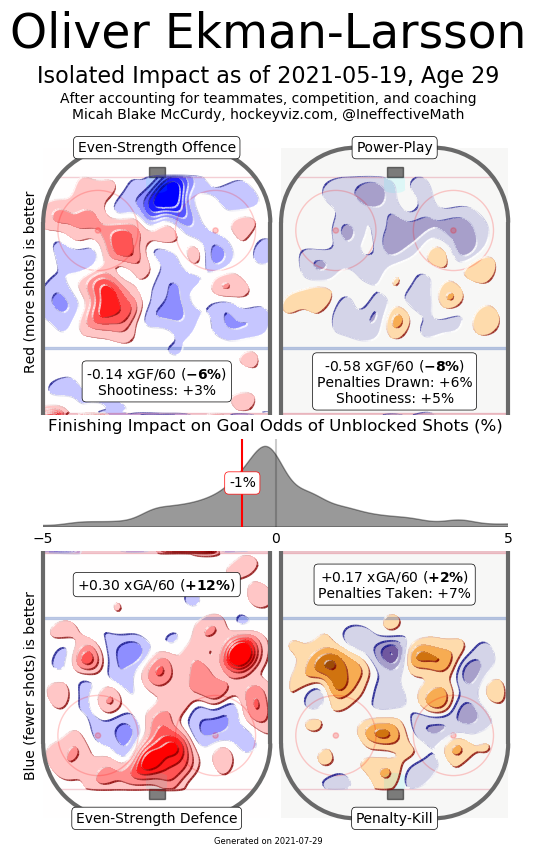

There are also various models out there that take into account context. For example, the incorporate contextual elements like zone starts, usage, and quality of competition and teammates. For Ekman-Larsson, the heatmap doesn’t paint a pretty picture.

Oliver Ekman-Larsson's isolated impact heatmap via HockeyViz.com

Oliver Ekman-Larsson's isolated impact heatmap via HockeyViz.comThe mountain of red in front of the Coyotes goal means that Ekman-Larsson is responsible for a ton of shot attempts from the most dangerous area of the ice, which aligns with him allowing the fifth-highest rate of high-danger shot attempts against among all NHL defencemen who played at least 500 minutes at 5-on-5 last season.

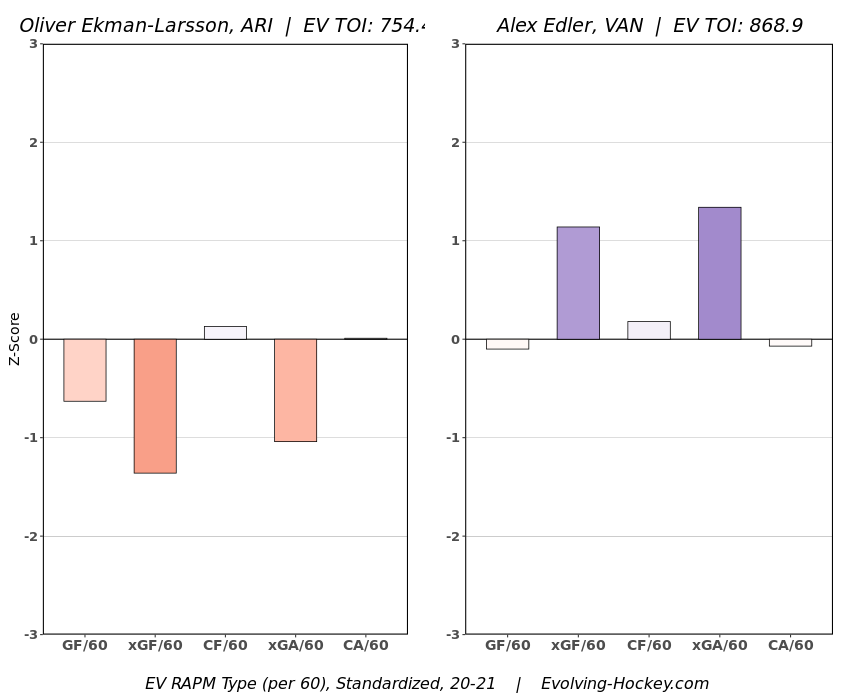

, which uses a different method to account for context.

Using their RAPM charts, we can directly compare two players, in this case Ekman-Larsson and Edler.

Oliver Ekman-Larsson vs Alex Edler — RAPM chart via Evolving-Hockey.com

Oliver Ekman-Larsson vs Alex Edler — RAPM chart via Evolving-Hockey.comIn terms of both expected goals for and against, Edler was significantly better than Ekman-Larsson last season. Judging by this model, Ekman-Larsson might not be the upgrade on Edler that some might expect.

It’s not that Ekman-Larsson played for a worse team that might affect his results. After all, the Coyotes finished last season with a better record and goal differential than the Canucks.

These are the results that Ekman-Larsson has been getting over the past several seasons. What these numbers don’t show, however, is how he’s been getting those results. That requires the eye test — you have to watch him play.

So I did.

Bring on the eye test

I watched 85 Ekman-Larsson shifts across three games spread throughout the 2020-21 season, looking for the positives and negatives of his game. Was there anything in those shifts to explain Ekman-Larsson’s ugly results from the analytics? Were there signs that he might be able to bounce back and improve in Vancouver?

Let’s be clear: 85 shifts is still a small snapshot of Ekman-Larsson’s game. Any observations from this snapshot don’t really overrule the data from hundreds of his shifts, but they can still provide some insight.

The first observation is a general one: Ekman-Larsson was mostly fine.

In most of the shifts that I watched, Ekman-Larsson played a respectable defensive game. Many shifts passed without incident because Ekman-Larsson was in the right position defensively. Most of the time he made safe, simple plays with the puck — in fact, he was often at his best when he played a simple game.

There are two issues here. One is that if you’re paying a guy over $7 million to be a number one defenceman, you likely want him to be . The other issue is that there were many occasions when Ekman-Larsson wasn’t fine at all and they point to why his underlying analytics haven’t been pretty.

But let’s start with some of the positives.

Quarterbacking the power play

It shouldn’t come as a surprise that one of Ekman-Larsson’s biggest strengths is the power play. He has 55 power play goals in his career, which is fifth among active defencemen, and 14 of his 24 points last season came on the power play.

When Ekman-Larsson was on the power play in the shifts I watched, he was typically the puck carrier coming out of his own zone, choosing whether to use the drop pass or a pass to the wing to gain the zone. He was typically pretty effective in this role.

Once in the offensive zone, Ekman-Larsson typically didn’t create plays from the point, but kept the puck moving crisply to his forwards on the sideboards. His positioning at the point to support the puck-carrier and provide an outlet showed his intelligence and veteran savvy, but he wasn’t quite as mobile as I’ve seen Ekman-Larsson in the past, where he would frequently switch spots with a forward to play on the sideboards or even roam into the slot.

Here’s an example of his puck movement at the point on a Phil Kessel goal. The passes are not anything fancy, but they’re crisp, quick and confident.

Here’s another example from the same game, as he keeps the puck moving across the point, opens up for a potential one-timer, then releases back into a support position and makes a one-touch pass to the opposite side before eventually getting a shot through traffic.

As you might guess from his career goal totals, Ekman-Larsson has a great shot. While he only managed three goals this past season, he’s been in the double digits in goals seven times in his career, including a career-high 23 goals in the 2014-15 season.

Here’s one of his three goals from last season, which also showcases a smart pinch on a ring-around and some excellent vision before opening up for a one-timer that he drills past Philip Grubauer.

The one issue with all of this power play prowess is that the Canucks already have Quinn Hughes to quarterback the first unit. Are they really going to take Hughes off that unit in favour of Ekman-Larsson? It’s exceedingly unlikely.

Ekman-Larsson bounced between the first and second unit with the Coyotes last season, averaging 2:24 in ice time per game on the power play. The defencemen on the Canucks’ second unit averaged closer to one minute per game on the power play.

Unless the Canucks significantly change how they distribute ice time between the first and second unit, Ekman-Larsson will have limited opportunities to have an impact on the power play.

Limited even-strength offence

Ekman-Larsson had a tougher time contributing to even-strength offence last season. His 0.73 points per 60 minutes at 5-on-5 was the lowest of his career and he managed just one even-strength goal.

Statistically, it doesn’t look like a bounceback is on the way. The Coyotes’ shooting percentage when he was on the ice was 7.48%, which is actually the highest it’s been for Ekman-Larsson in the past four years.

He’ll likely get the chance to play with some excellent finishers in Ā鶹“«Ć½Ó³»but it’s not like he was playing with scrubs in Arizona. The two forwards he played with most frequently were Phil Kessel and Clayton Keller — Kessel is one of the best shooters in the NHL and Keller is no slouch either.

Part of the issue is that Ekman-Larsson was a bit of a mixed bag when it came to breaking the puck out of his own zone and transitioning the puck up ice.

It certainly didn’t make a good first impression when the very first shift I watched featured this ugly giveaway after the opening faceoff against the San Jose Sharks.

When Ekman-Larsson kept things simple, he made effective passes on the breakout. When he tried to make stretch passes, however, they frequently missed the mark or led to turnovers in the neutral zone. Sometimes he would hold onto the puck too long as passing options dried up, forcing a low-percentage pass or just banking the puck off the glass and out.

Other times, his puckhandling seemed to abandon him, with simple passes bouncing off his stick. That happens to every player, no matter how talented, but it happened frequently enough with Ekman-Larsson that it was hard to ignore, particularly for a player who seemed so sure-handed with the puck on the power play.

I don’t want to give a false impression. There were plenty of times where Ekman-Larsson had no issues on breakouts, such as this strong work by him and his most frequent partner, Ilya Lyubushkin, to evade the aggressive Avalanche forecheck. You can’t hear it in a gif, but Ekman-Larsson was yelling instructions to Lyubushkin — or “Boosh” as he called him — the whole time.

The quick shift in weight in the neutral zone by Ekman-Larsson is nice to see, creating the space for an easy pass for a zone entry.

Jump up superstar

While Ekman-Larsson wasn’t quite the transition machine that you might expect, he showed that he was capable of jumping up in the rush when I watched him and he picked his spots well, making sure he wouldn’t get caught in a counter-attack.

Take this play against the Minnesota Wild for example, where he starts the breakout with a reverse behind his own net, then skates the length of the ice to pick up a pass and get a hard shot on net.

Of course, “picked his spots” is another way of saying he didn’t do it very often. At the peak of his career, the smooth-skating Ekman-Larsson was always a danger to add another layer to the attack by unexpectedly jumping up in the play. That doesn’t seem to be quite as much of his game anymore for whatever reason.

Perhaps it’s simply a natural result of slowing down with age or injuries accumulated over the years, such as his knee surgery in 2019. Combine that with some inefficient skating mechanics, as pointed out by former Toronto Maple Leafs analyst Jack Han, and it’s understandable that Ekman-Larsson might not have the speed he once possessed to jump up in the play.

Ekman-Larsson’s skating leads back to a key strength of his defensive game: his reach and his stick.

Not just a good stick; an excellent stick

Despite losing a step in his skating, Ekman-Larsson still manages to defend against the rush well thanks to exceptional use of his stick.

This was a clear and obvious strength of his game, as he used his stick well to steal pucks, break up passes, and disrupt rushes. Well-timed sweep checks sent the puck off an opponent’s stick and out of the zone and quick pokes created turnovers to send the puck the other way.

He also used his stick to make up for a lack of footspeed, like in the clip below. He can’t win the race to the puck, but he uses his stick positioning to cut off a lane to the net, then leads with his stick to poke the puck away before pinning his man to the boards.

Here’s another example against the Colorado Avalanche, as Ekman-Larsson is nearly beat wide by Andre Burakovsky, but he uses his reach to get around Burakovsky’s outstretched arm and poke the puck free.

Again against the Avalanche, Ekman-Larsson uses his stick to first pick off a pass, then gets his stick in to knock away a centring pass from behind the net. There are some positioning issues here, but Ekman-Larsson’s quick stick is able to make up for it.

He also used his stick effectively in the neutral zone, attacking aggressively when he had the opportunity and using quick stick checks and pokes to divest an opponent of the puck, like in the clip below against the Minnesota Wild.

Sometimes, however, it seemed like he was overly reliant on his reach and stick. At times when it would have been better to close the gap and use a more physical play to eliminate a rush, he instead would lean over and reach with his stick.

As good as his stick is, it’s easy for a small rubber puck to get by a stick or even take an odd bounce over a blade. When his stick didn’t work, that’s when things sometimes went sideways for Ekman-Larsson, which segues to a major issue.

Netfront negligence

When we focus in on Ekman-Larsson’s in-zone defence is when things start to get a little shaky and it becomes more clear why the Coyotes gave up so many high-danger scoring chances in front of the net when he was on the ice.

Take this moment on the penalty kill against the San Jose Sharks. As a puck is sent down low, Ekman-Larsson reaches out with one hand on the stick to poke it away. That’s when his check lifts his stick, pivots, and takes the puck hard to the net with inside position.

What became clear while watching Ekman-Larsson is that it’s often far too easy to get inside position on him and get to the net for a scoring chance or a goal.

Take this Nazem Kadri goal for the Avalanche as an example. Ekman-Larsson gets caught puck-watching off a lost faceoff and loses track of Kadri behind him. By the time he recognizes the danger and tries to wrap up his stick, it’s too late and Kadri deflects in the goal.

There are more troubling examples too, such as this play against the Sharks where Ekman-Larsson abandons the front of the net to help out a lost puck battle, when the true danger was Tomas Hertl going to the net behind him.

The real issue is it seemed to be a pattern. Here he again left the front of the net, anticipating a ring-around attempt that never came. Instead, he left the backdoor wide open for a scoring chance.

This isn’t cherry-picking a few bad plays: the Coyotes gave up a ton of high-danger chances with Ekman-Larsson on the ice and this is part of the reason why. Ekman-Larsson would frequently leave the front of the net open to try to pick off a pass he anticipated or poke a puck away from a player already being checked by a teammate.

When that type of play works, a defenceman looks heads up and savvy, creating a turnover seemingly out of nowhere. The problem is that it’s a high-risk play that can prove costly.

The reason this is so concerning is that it’s not a mechanical issue that he could correct or a system that doesn’t play to Ekman-Larsson’s strengths. It’s decision-making and poor reads. That’s a lot harder to fix, particularly for a 30-year-old defenceman.

Then there’s an issue like on this goal, where he just seems to lose focus. It’s not just that Ekman-Larsson doesn’t recognize the developing rush as he comes off the bench but that he stops up above the hashmarks instead of chasing down and taking away the open man.

When physical, Ekman-Larsson's effective

There was a time when Ekman-Larsson was a very capable in-zone defender, with aggressive reads to close space, break up the cycle, and start play the other way.

Sometimes that effective in-zone defence would pop out, like in this play against the Wild, where he combined a good read with a quick stick and a hip into his opponent. That freed up the puck and, after a quick stickhandle, a neat pass on the backhand enabled the breakout.

He also had a strong shift against the Wild where he was tasked with shadowing their most dangerous player, Kirill Kaprizov. He was all over him the entire shift, giving him no room to maneuver.

When Ekman-Larsson engaged physically in the defensive zone instead of just relying on his stick, he was at his most effective, such as this shift against the Avalanche. Twice he erases Avalanche players against the boards with his size, freeing up the puck in hopes a teammate can get to it.

He showed that he can do it against the rush as well, squeezing an opponent against the boards to create a turnover.

If the Canucks could see a little more of this Ekman-Larsson next season, then maybe they’ll be okay. But the occasions where he engaged physically were too few and far between. That could again be connected to declining mobility preventing him from effectively closing gaps against speedy opponents.

What’s the verdict?

There’s no saying exactly how a player will fit in on a new team with a new system and there are both reasons for optimism and cynicism from watching Ekman-Larsson play.

Ekman-Larsson is at his best on the power play, where he is confident and decisive with the puck and is able to find room to use his shot. On breakouts at even-strength, he succeeds when he makes the simple play. Defensively, he’s got a great stick, but is most successful when he uses that great stick in combination with closing gaps and using his size to separate opponents from the puck.

Those are the positives.

To be honest, I was hoping that watching Ekman-Larsson play would assuage some of the concerns raised by his analytics. Instead, it just confirmed them.

Defensively, he too often abandons the front of the net, leading to dangerous scoring chances. Even when he stays in front of the net, he’s frequently too passive, allowing opponents to get inside position instead of boxing them out physically. His declining mobility allows opponents to beat him wide and his excellent reach and stick can only make up for so much.

Offensively, he doesn’t create much at even-strength as his stretch passes don’t often find their target and he’s not as capable of jumping up in the rush as he once was.

Ekman-Larsson’s usage in Ā鶹“«Ć½Ó³»is unlikely to get any easier than it was in Arizona. He’ll likely have to play shutdown minutes with one of Travis Hamonic or Tucker Poolman. Given his issues defending the front of the net, that seems like a major concern.

He’s also unlikely to get as much time on the power play, though it might behoove the Canucks to more evenly split their power play time between the first and second unit. With the addition of Ekman-Larsson, his Coyotes teammate Conor Garland, and Vasily Podkolzin, the Canucks will have the personnel to make a more dangerous second unit than in previous years.

It’s certainly not all negative. Ekman-Larsson is really, really good with his stick and he’ll make plenty of defensive plays that could convince Canucks fans that the concerns over his defensive game were overblown. His shot is too good to only score three goals and he’ll likely pop a few more with the Canucks.

The question is whether those positive contributions will outweigh the negatives.