A Canadian team hasn’t won the Stanley Cup since 1993, when Patrick Roy and Vincent Damphousse led the Montreal Canadiens over Wayne Gretzky and the Los Angeles Kings.

Could the Canucks be the team to finally break the Canadian Cup drought? Some suggest they’re the most likely to do so. , 31% of hockey fans think the Canucks will be the next Canadian team to win the Stanley Cup, well ahead of the next highest-ranked team, the Montreal Canadiens, at 19%.

TSN’s Frank Seravalli agrees with the fans and broke down why he thinks : a fantastic one-two punch at centre, an elite number-one defenceman, bonafide top-six wingers, and quality goaltending.

It’s understandable why people would be high on the Canucks. No other Canadian team got as far as they did in the 2020 playoffs, just one game from the Western Conference Finals. They’ve got a talented young core led by Elias Pettersson and Quinn Hughes and look like a team on the rise. As Seravalli said, “The Canucks’ window is just cracking open.”

There are reasons to temper that optimism with caution. We’ve seen “young teams on the rise” fail to take that next step many times in the past. For a couple of examples, we just need to glance one province over at Alberta.

Five years ago, the Calgary Flames won a playoff round after a long playoff drought led by a pair of young stars. They were expected to be a perennial playoff team and potentially even challenge for the Pacific Division lead. Instead, they missed the playoffs in two of the next three seasons and haven’t won a playoff round since beating the Canucks in 2015.

Three years ago, it was the Edmonton Oilers. They won a playoff round, then pushed the Anaheim Ducks to Game 7 in the second round. It seemed like the Oilers had finally figured things out after so many years of futility. Led by the best player in the NHL, with other young talents around him, the Oilers were a .

Instead, the Oilers have missed the playoffs in three straight seasons.

In other words, winning a playoff round with a young and exciting core does not guarantee future success. Anointing the Canucks the next great Canadian team might be a little premature.

The big question is, are the Canucks bound for the same fate as the Flames and Oilers? How can they steer clear of the same pitfalls and avoid missing the playoffs next season?

I spoke with two writers that cover the Flames and Oilers, and to see where the two teams went wrong.

Let’s start with the similarities. Just as the Canucks were led by Pettersson and Hughes, the Flames and Oilers had their own dynamic young duo. For the Flames, it was Johnny Gaudreau and Sean Monahan. The Oilers had a pair of Hart Trophy winners.

“Connor McDavid and Leon Draisaitl were leading the way,” said Willis. “Everybody looked at it and thought, ‘These guys are doing this now, what are they going to do when they’re 23-24?’”

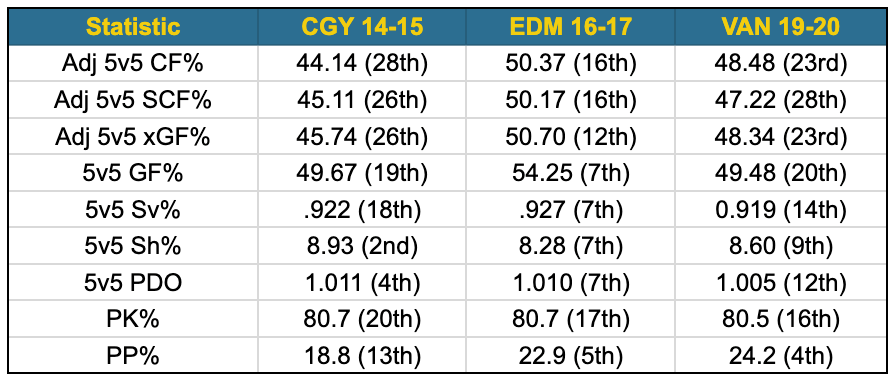

Let’s take a look beyond those superficial similarities by comparing their underlying numbers in the regular season. That can give us a better idea of how each team was performing heading into the playoffs and the following season.

Comparing the 2019-20 Canucks with the 2014-15 Flames and 2016-17 Oilers.

Comparing the 2019-20 Canucks with the 2014-15 Flames and 2016-17 Oilers.All statistics are via Natural Stat Trick and the NHL. Here’s a quick breakdown of what we’re looking at:

- Adj 5v5 CF% = Score and Venue-Adjusted Corsi-For Percentage, which is the percentage of shot attempts taken by a team at 5-on-5. Above 50% means you’re outshooting your opponents.

- Adj 5v5 SCF% = Score and Venue-Adjusted Scoring Chance-For Percentage

- Adj 5v5 xGF% = Score and Venue-Adjusted Expected Goals-For Percentage, which is a metric that incorporates both shot quantity and quality to estimate the number of goals each shot is worth.

- 5v5 GF% = Goals-For Percentage. Above 50% means you’re outsourcing your opponents.

- 5v5 Sv% = Save Percentage at 5-on-5.

- 5v5 Sh% = Shooting Percentage at 5-on-5.

- 5v5 PDO = A combination of save and shooting percentage that is used as a proxy for luck. Finishing well above 1.000 generally indicates good luck and well below 1.000 generally indicates bad luck.

- PK% = Penalty Kill Percentage

- PP% = Power Play Percentage

Looking at the Flames in the 2014-15 season, there were some very clear warning signs that they were not as good as they seemed. In terms of puck possession metrics, they were near the bottom of the NHL.

The Flames managed to draw nearly even in goal differential at 5-on-5, however, because they had one of the best shooting percentages in the league. That sky-high PDO had analytics aficionados sounding the alarm, but their defenders simply called them opportunistic: they didn’t out-chance their opponents, but finished their chances when they got them.

In addition, the Flames also got a lot of goals in unusual situations. They led the league in 4-on-4 goals with 14, and 6-on-5 goals with 9. They had 12 goals into an empty net, 6th in the NHL. They came from behind to win close games and closed-out tight games with empty-net goals, defying analytics all the while.

“The calling card of that team for quite a while was run-and-gun hockey,” said Pfeil. “It’s exciting from a fan perspective, you’re getting a serotonin rush watching it, but any sensible person would know this isn’t going to work out long term.”

“They played this style of hockey under Bob Hartley where you’re constantly out-shot,” he added. “You’re always having to come back in the third period.”

The Oilers, on the other hand, had more positive signs in their puck possession numbers, where they were at least average in corsi, scoring chances, and expected goals. Combined with some above-average goaltending and finishing, the Oilers were adept at out-scoring their opponents at 5-on-5. They also had one of the league’s best power plays.

Still, there were some warning signs.

“Cam Talbot had a career year. He played 73 games, which led the league,” said Willis. “When you have a goalie with a career year play basically every night, that covers up a lot of sins.”

Talbot kept that performance going through the playoffs, playing a big role in the team getting past the San Jose Sharks and pushing the Anaheim Ducks to seven games. The Oilers had plenty of offence, but also some significant defensive holes, which Talbot helped fill. Expecting a goaltender to repeat that kind of performance was unrealistic.

The Canucks can see a reflection of themselves in both the 2014-15 Flames and the 2016-17 Oilers. Like the Flames, their puck possession metrics are below-average an, in some cases, near the bottom of the league. They made up for that with strong goaltending and finishing, as well as a top-tier power play, like the Oilers.

Still, the Canucks weren’t quite as lucky as either the Flames or Oilers, so perhaps there’s less reason for concern in that area.

Where the Flames went wrong

What’s intriguing about the Flames in the 2015 offseason is that they didn’t really make any significant missteps. In fact, they made some savvy moves, like acquiring Dougie Hamilton and signing Michael Frolik. The Hamilton acquisition, in particular, added the young star defenceman that the team was missing in their young core and gave the team, on paper, one of the best defence corps in the league.

“[Hamilton] should have been the difference-maker,” said Pfeil, “but it’s not enough when you’re playing in a system like that.”

According to Pfeil, the offseason moves were not enough to overcome the inevitable regression after they outperformed expectations in the previous year. Veteran Jiri Hudler, who led the Flames in scoring in 2014-15, couldn’t repeat his career year. The Flames’ goaltending tandem of Karri Romo and Jonas Hiller, who had been solid in 2014-15, was well-below average in 2015-16.

Most importantly, their coaching held them back.

“[Hamilton] didn’t get a lot of prime minutes alongside Mark Giordano,” said Pfeil. “He spent a lot of time with Dennis Wideman and Kris Russell that season. If you play this really promising player with an anchor or somebody who’s going to drag down the ceiling of their maximum performance, you’re handcuffing yourself.

“It’s not just about getting the best players on paper, but setting them up to be successful.”

Whether it was the run-and-gun style of hockey or not putting players in a position to succeed, Hartley was fired after the 2015-16 season.

Another issue is that the Flames didn’t get a lot of help from their prospect pool. The 2013 and 2014 drafts didn’t yield much outside of their first-round picks, so they were unable to supplement their lineup with young players on cheap contracts.

“They didn’t get any players of value that could have helped them in the 15-16 season, where they saw the regression to the mean, or the next season,” said Pfeil. “So they relied heavily on the roster that they had assembled.”

The problem was, the roster as assembled had some major holes.

“You had the likes of Brandon Bollig playing 54 games and Lance Bouma, Deryk Engelland — they didn’t have a great roster outside of the top guys,” said Pfeil.

By the trade deadline, the Flames were clear sellers and were able to sell high on Kris Russell and Jiri Hudler.

You can see potential parallels with the Canucks. What if, like Hudler, J.T. Miller can’t repeat his career year where he led the team in scoring and regresses? What if the tandem of Jacob Markstrom — or a free agent goaltender — and Thatcher Demko stumble next season?

If that happens and the Canucks find themselves out of the playoffs by the trade deadline, will they become sellers like the Flames did, taking a short-term hit to set themselves up for the future?

There are some clear differences, however, between the two teams.

“Coaching-wise, I think the Canucks are miles ahead of where the 14-15 Flames were when they snuck into the second round,” said Pfeil. “And they have one calling card that I keep coming back to: they have Quinn Hughes. The Flames didn’t have that.”

Where the Oilers went wrong

The Oilers were in a different position than the Flames. Judging from the underlying puck possession numbers, they were not a paper tiger like the Flames were and a good offseason would potentially set them up for success in the future.

They didn’t have a good offseason.

instead of taking another step forward the season after winning a playoff round, the Oilers took a step back. Their underlying numbers were slightly worse than the previous season and, with their goaltending regressing, they crashed and burned.

Talbot was once again workhorse for the Oilers, but he fell to a .908 save percentage in 2017-18. Their young and unproven backup, Laurent Brossoit, was even worse, and the midseason acquisition of Al Montoya did little to improve the situation.

“Their playoff results — and regular season results, for that matter — were so dependent on goaltending,” said Willis. “You look at a team that’s getting its results through spectacular, unsustainably good goaltending: a good team can win a Cup with that kind of goaltending.

“A mediocre team can look like a good team with that kind of goaltending.”

Willis’s use of the word “mediocre” in reference to the 2016-17 Oilers immediately brings to mind the this season that suggested the Canucks were likewise a mediocre team. That’s an uncomfortable parallel.

The Oilers didn’t help their cause, however, with their offseason.

“I don't think people appreciated the level of the talent exodus, both through managerial moves and through injury in the aftermath of that season,” said Willis. “In terms of player losses, there were two big ones right off the bat: Jordan Eberle and Andrej Sekera.”

After a disappointing playoff performance, Eberle was traded to the New York Islanders for Ryan Strome. That deal quickly proved lopsided: Strome put up 13 goals and 34 points in Edmonton, while Eberle had 25 goals and 59 points in Long Island.

“They flipped [Eberle] for Ryan Strome, they flipped Strome for Ryan Spooner, they flipped Spooner for Sam Gagner — it was , but in reverse,” said Willis. “Eberle had a miserable playoffs and fans were largely really supportive of the decision to move him out, but I think if you look at what he’s done with the Islanders, it’s readily apparent that first playoff experience in Edmonton was not at all indicative of the kind of player he was going to be.”

Moving out Eberle continued the talent drain in Edmonton that had begun before the 2016-17 season.

“A lot of the problems that would sink the Oilers later on were already baked into the mix when they were enjoying that success,” said Willis. “You look at the Taylor Hall for Adam Larsson trade, which has been pilloried in the years since. At the time, there were columnists writing about what a great deal it was because, with Larsson, these Oilers were a different team, a team that could win playoff rounds.

“Ultimately that was illusory.”

With Hall and Eberle shipped out, the Oilers had limited options to play on the wings with their two superstar centres, McDavid and Draisaitl. There was a simple solution, but it’s one that sewered their depth.

“One of the big things for the Oilers was that Draisaitl and McDavid were one line,” said Willis, “so they didn’t have a one-two punch at centre, they had one great line, and that really hurt them.”

Sekera, on the other hand, was an unforeseen loss. A key contributor in 2016-17, Sekera got injured in the playoffs against the Ducks, playing a role in them losing that series. He didn’t return to the lineup until late December in the 2017-18 season and wasn’t the same player.

“He was the number three defenceman in terms of overall ice team, but he played both special teams and he really fortified the second pairing with Kris Russell,” said Willis. “There was no way of knowing that was going to happen, but players get hurt and that can alter the trajectory of the franchise.”

Along with losing a capable player, the Oilers took a financial hit as they ended up buying out Sekera. His buyout is on the Oilers’ books through the 2022-23 season.

Sekera’s contract ended being onerous for the Oilers, but it wasn’t the only bad contract on the books. The Oilers were as quick to re-sign Russell after a strong playoff performance as they were to move Eberle after a poor one, and he’s since slid down to the third pairing with a $4 million cap hit. Then there’s the big one: Milan Lucic and his $6 million anchor of a contract.

“When I look at the Canucks and the Oilers, one of the things that strikes me as similar and, if you're a Canucks fan, you hope I'm wrong about this, but they have a lot of bad contracts baked into the mix that are going to get worse as years go by,” said Willis. “Those deals were maybe not great value when they signed them, but they were going to get worse and worse as time went by.

“When I look at Vancouver, I see Antoine Roussel, I see Jay Beagle, I see Loui Eriksson and Brandon Sutter. Edmonton didn't have the ability to solve problems when it ran into them because they didn't have any discretionary money, because so much money was tied up in bad contracts. I look at Â鶹´«Ă˝Ół»and I wonder if they're not looking at potentially having the same outcome.”

Beyond that parallel, a couple of other lessons can be drawn from the 2016-17 Oilers. A clear one is to not overvalue the small sample size of the playoffs, which led to re-signing Russell and shipping out Eberle.

The parallel in this case is likely Brock Boeser. While Boeser’s playoffs weren’t as disappointing as Eberle’s performance in 2017, more was expected from the winger than 4 goals in 17 games. He’s been dogged by trade rumours for months, but moving him out now could be a similar mistake to trading Eberle.

Even if the Canucks re-sign Tyler Toffoli, that doesn’t make Boeser expendable. As we see from the Oilers, quality top-six wingers matter when it comes to getting balanced scoring.

Much like Pfeil and the Flames, however, Willis sees a clear difference between the current Canucks and the 2016-17 Oilers: the Canucks have Quinn Hughes. The Oilers don’t.

“You look at Darnell Nurse, you look at Oscar Klefbom — those are good defencemen. Adam Larsson was a relatively young defenceman and a good one in 2017 as well, those are all good players, but you cannot replace a number one defenceman,” said Willis. “It’s an extremely difficult piece to get.”

Conclusions

While the 2014-15 Flames and 2016-17 Oilers share some similarities, the reasons why each team disappointed in subsequent years are very different.

The Flames made some good moves in the offseason, but they failed to properly address their faults from the previous season that had been masked by unsustainable shooting percentages and third-period comebacks. The systemic flaws from their style of play and coaching were their downfall.

The Oilers, on the other hand, were the authors of their own demise, doubling down on a player with a questionable impact in Russell, and trading away their best winger in Eberle. They also inadequately prepared for potential regression from their goaltender, trusting in an unproven young backup and a journeyman veteran behind their starter.

This offseason, the Canucks need to be brutally honest in assessing their team’s flaws, in a way that the Flames were not. They need to be realistic about the possibility of their veterans performing worse next season and understand that not all their young players will take a step forward.

The Canucks can’t dismantle aspects of the team that made them successful, like the Oilers did when trading Eberle. They need to create some cap flexibility by moving out bad contracts, which the Oilers were not able to do. Perhaps most importantly, they need to avoid a goaltending situation like the Oilers, where they’re not prepared to handle regression.

In some ways, however, the Canucks are better off than the Flames and Oilers because their two franchise players are a centre and a defenceman instead of two forwards.

In Calgary, Monahan and Gaudreau play on the same line, so their impact is shared. Up until this season, McDavid and Draisaitl primarily played on the same line as well. Pettersson and Hughes, however, can’t play on the same line, so their impact is spread out by necessity.

Will that be enough for the Canucks to avoid the same fate as the Flames and Oilers?

.JPG;w=120;h=80;mode=crop)