Anyone who has ever flown from �鶹��ýӳ��to Prince Rupert, Prince George or Fort Nelson and looked out the window may have wondered to themselves: “How can B.C. possibly be running out of trees to cut?”

B.C.’s forest sector was beaten to a pulp in 2019, as a “perfect storm” of market, policy and natural forces converged, triggering multiple sawmill closures and curtailments, and spurring anger among laid-off workers towards politicians and conservationists.

When the Sierra Club and Wilderness Committee tried to hold an event in Campbell River on November 25, it was shut down by the city and police, for fear of confrontation.

What was supposed to be a town hall talk on old-growth forests and climate change turned into an impromptu pro-logging rally, according to the Campbell River Mirror. “It’s not a very popular time to be an environmentalist,” said Mark Worthing, a climate and conservation campaigner for the Sierra Club.

Nor is it a popular time to be a BC NDP cabinet minister in ridings where sawmill workers and loggers are now struggling to meet mortgage and car payments.

There, the general downturn in forestry is aggravated by a prolonged strike by Western Forest Products (TSX:WEF) workers.

When Claire Trevena, NDP MLA for North Island, held a recent town hall in Campbell River, angry, out-of-work loggers accused government of indifference to their plight. B.C. forestry companies have gone from making record profits in 2017 and 2018 to posting losses in 2019.

“The companies are bleeding,” John Desjardins, forest products lead for KPMG in Canada, said at a recent Greater �鶹��ýӳ��Board of Trade talk on forestry. “They’re in the red.” Six sawmills permanently closed in 2019, and with shifts that have been eliminated at mills that are still operating, it adds up to the equivalent of eight sawmills.

Thousands of sawmill workers, truck loggers and related service workers were laid off in 2019. Employment and Social Development Canada confirms that unemployment insurance claims went up in B.C. by 1,170 between September 2018 and the same month in 2019.

The effects are most immediately felt in Interior towns like 100 Mile House, where forestry accounts for one out of every four jobs. But forestry accounts for one-third of B.C.’s exports, and even in Vancouver, the economic impact will be felt, because more sawmill closures are inevitable – possibly followed by pulp mill closures.

“More than 40% of forestry jobs are located in �鶹��ýӳ��and in the southwest part of the province,” Susan Yurkovich, CEO of the BC Council of Forest Industries, recently told the Greater �鶹��ýӳ��Board of Trade, adding that forestry in B.C. accounts for 100,000 direct and indirect jobs. Forestry is cyclical, and B.C. is used to downturns.

“This time it’s different,” Yurkovich said. Other provinces, like Quebec, have not seen the wave of sawmill closures that B.C. has. Whereas B.C. used to be “the last man standing” when a cyclical downturn came in forestry – owing to the fact it was a low-cost jurisdiction – that’s no longer the case. One of the biggest problems has become a lack of economically harvestable timber.

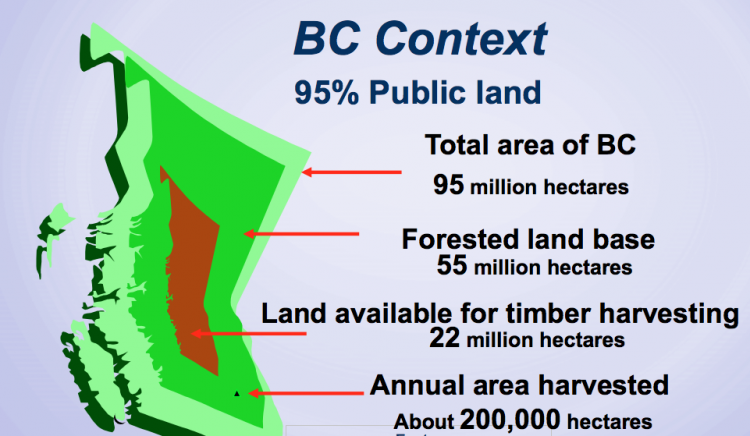

In a province with 55 million hectares of forest – an area roughly three times the size of the U.K. – how is that possible? The most visible answer is the toll taken by the mountain pine beetle, and by forest fires. But it’s not just pests and natural disasters that have eaten up B.C.’s timber supply.

Pressure to preserve forests for conservation or yield them to recreation and increased urbanization have resulted in a significant shrinkage of the working-forest land base.

“We need to invest in and protect the working-forest land base,” Yurkovich said.

“We should decide on the size of the working-forest land base, and then we should lock it in.” She added that the industry is burdened by a “jungle” of regulations that increase operating costs.

“We need to thin out that jungle,” she said.

'We need to invest in and protect the working-forest land base' – Susan Yurkovich, COFI. Photo: Nelson Bennett

'We need to invest in and protect the working-forest land base' – Susan Yurkovich, COFI. Photo: Nelson Bennett But drawing a moat around B.C.’s working forests is easier said than done. For one thing, it’s not likely to win the support of conservation groups, which continue to press for less logging, not more.

“I can see what [Yurkovich] might be gunning for there,” the Sierra Club’s Worthing said.

“We’d never particularly stand behind super checkerboard, black-and-white sacrifice zones and conservation zones that have discrete lines in that way, because that’s not really how ecosystems work.

“I would say that the timber-harvesting land base hasn’t been chewed away at by other interests. It’s been really heavily logged on really short rotations. And I would argue that the large tenure holders and the major logging corporations have basically run through a resource far too fast and have not been managing their existing timber-harvesting land base sustainably.”

On paper, B.C. should theoretically still have sufficient working forests to supply mills. In reality, some of the timber deemed working forest is too costly under the current system to log. Jim Girvan, an independent forestry consultant, points to the Prince George timber supply area (TSA) as an example.

At eight million hectares, it is the single largest TSA in B.C. But once all the exclusions for recreation, wildlife habitat conservation, old-growth preservation and other measures are accounted for, it leaves just three million hectares that can be logged, Girvan said.

“They identify the land base on paper, but it’s not a circle on a map because you still have landscape restrictions,” Girvan said.

The allowable annual cut in B.C. is nominally bigger than what is harvested. Photo: BC Government

The allowable annual cut in B.C. is nominally bigger than what is harvested. Photo: BC GovernmentIf the Prince George TSA is further apportioned as First Nations tenures, as has been proposed, it would reduce the allowable annual cut (AAC) a further 3% to 4%, Girvan said.

“There’s another shift gone, just because you’re drawing different lines on a map,” Girvan said. The coastal cut has shrunk by 8.5 million cubic metres since the 1990s.

That is enough to supply 10 coastal sawmills, Girvan said. The Great Bear Rainforest alone took 6.4 million hectares. Only 295,000 hectares were preserved for logging. “In that 295,000 hectares, now you’re very restricted on what you can log.”

Increased log exports have been blamed, in part, for the shortage of timber on the B.C. coast – something the NDP government has been trying to address with new regulations.

Girvan doesn’t think any of the regulations that the government has adopted will address the fundamental problem of access to timber.

“It’s not log exports – it’s because the cut went down,” Girvan said. “The cut’s going down because they’re systematically preserving more and more timber for a variety of reasons.”

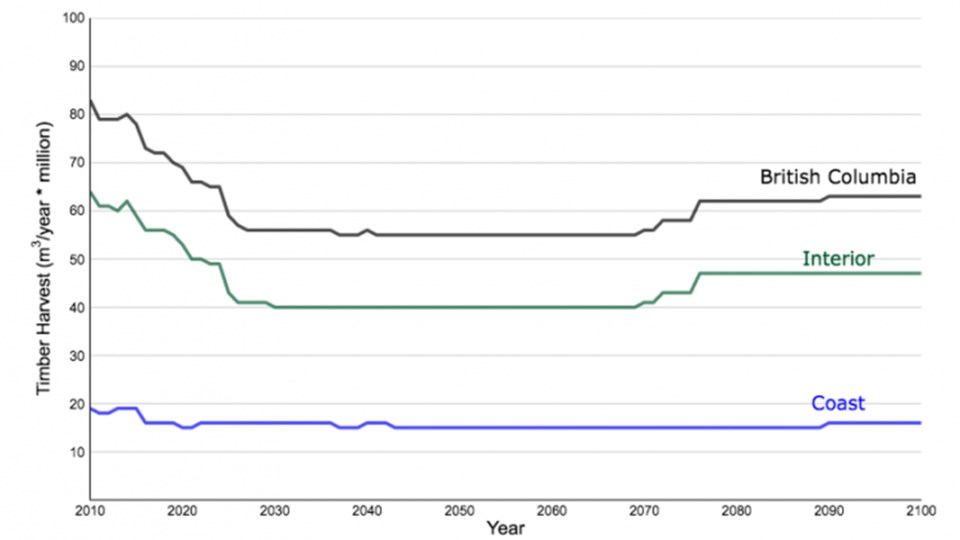

The long-term annual allowable cut will continue to decline, especially in the interior.

The long-term annual allowable cut will continue to decline, especially in the interior.While he agrees that declaring working-forest boundaries with regulatory goalposts that don’t move would go a long way to ensuring the long-term viability of forestry in B.C., Girvan said the pressure from urban development is unrelenting. He cites controversy over a plan to log in the Mount Elphinstone area of the Sunshine Coast as an example.

Despite having set aside 15,400 hectares for parks and conservation, and 2,900 hectares of old growth, the province is under continued pressure to stop logging in the area that is still designated for harvesting.

It has reduced the logging area on the south slope to just 27 hectares per year – half of what the AAC for that area would support. And just recently, the B.C. government called a halt to all logging in the Skagit River valley in an exclusion zone between Manning and Skagit provincial parks called the “doughnut hole.”

“The problem with putting a circle on a map and saying ‘This is logging’ is that it never gains traction because of this growing urban interface,” Girvan said. “Eventually somebody will move next door to it and say, ‘Oh no, no, you can’t log in my backyard.’”

While an ever-shrinking land base is part of the problem in B.C., the cost of harvesting is also a challenge. There are stands of trees that could be cut but which simply do not provide an economic return. And there are plenty of trees in the northern half of B.C., which could be opened up to logging, but the distance and remoteness would add to the cost of harvesting and transporting logs.

“You could move further north, but you run into economics,” said John Innes, the dean of the faculty of forestry at the University of British Columbia. He added that the working forests are not being managed in a way that maximizes the timber resource, the way they are in northern Europe.

“We could be growing our trees more intensively, we could be growing them faster, we could be producing a higher volume from the same area,” he said, adding that that would be a very long-term project. He also points out that it is the big forestry companies in B.C. that have been hit the hardest by the lack of timber, increasing costs and falling lumber prices. “It is still possible to make money with trees in British Columbia,” Innes said.

“We have the big mills focusing on dimensional lumber, and those are the ones that have been suffering. But if you look at the smaller specialty mills, they generally have been doing OK still.”

[email protected] @nbennett_biv

Read more from