A Canadian doctor practising near Boston who sounded alarm bells this summer over roadblocks he encountered trying to return to practice in Victoria says he’s excited about the province’s plans to smooth the path for international medical graduates and physicians.

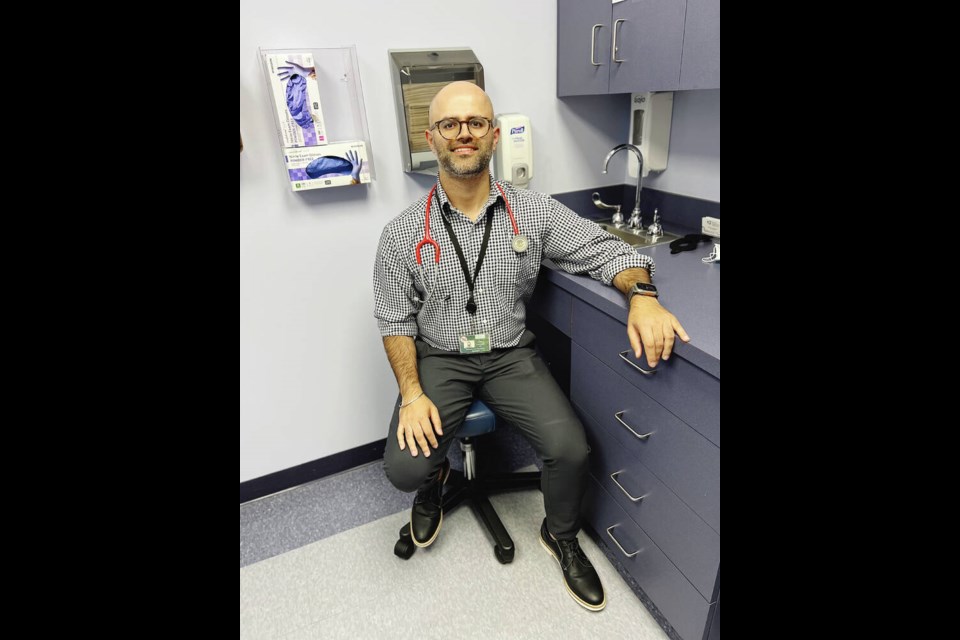

Madhur Kuckreja, 33, an internal medicine physician practising in Brockton, Massachusetts, was trained at St. George’s University, a Caribbean international medical school, before completing a residency at Georgetown Hospital in Washington, D.C.

He recently acquired a Washington state licence with the thought of moving to Seattle to be closer to his hometown of Victoria, after efforts to become licenced in B.C. seemed out of reach and costly. Now he’s looking at his options.

Kuckreja, reached by phone, called the changes announced by B.C. Premier David Eby on Sunday “great news.”

“It’s crazy all the changes they are making,” said Kuckreja. “I’m very optimistic but cautious.”

For medical graduates and doctors working outside Canada, the new suite of incentives includes the tripling of Practice Ready Assessment seats — the path for internationally educated graduates to be licensed to work in B.C. — to 96 by March 2024.

Internationally educated graduates not yet eligible for licensing in B.C. will also be able to work under supervision as “associate physicians” in acute and primary care settings.

The province is working with the Royal College of Physicians and Surgeons of Canada and the College of Family Physicians of Canada to allow graduates to start the accreditation process prior to arriving in B.C.

And the College of Physicians and Surgeons of B.C. is drawing up new bylaws in coming weeks to allow physicians who trained for three years in the U.S. to practise in community clinics and family practices.

The goal is for such U.S.-trained physicians to be practising in B.C. by January.

Kuckreja believes he falls under the opening for U.S.-trained physicians, as he did his residency in the U.S. and is board-certified there. “I will definitely apply for a B.C. medical license and see what the process is like,” he said. “I didn’t see this thing coming to be honest, so my plan was to move to Washington state and then at least be pretty close to home. But let’s see what happens now.”

Krukreja said his Canadian physician colleagues in the States are equally buoyed by the news out of B.C. “I think there’s a lot of interest.”

Born in India, Kuckreja moved to Victoria when he was eight, attending Quadra Elementary, Cedar Hill Middle School and Mount Doug High School. His parents and sister still live here.

“I visit Victoria two or three times a year — I still consider it home,” he said.

Kuckreja did his undergraduate degree at the University of Victoria but didn’t get into the University of B.C.’s medical school — “my dream school” — on his first try. After seeing colleagues try for years, he was unwilling to wait to reapply and shifted to his backup plan: the Caribbean school.

Reading news of the physician shortage here, Kuckreja thought it was time to return home to be closer to his family.

But his application for a B.C. medical licence was denied, and he was told he needed another full year of training and to pass several exams, including the $1,375 Medical Council of Canada Qualifying Exam.

Kuckreja, who works at Brockton Neighborhood Health Center, said he’s already well into his profession. He’s gone to medical school, completed his fellowship “and then after that we’re asked to do more training?” It’s frustrating, he said.

After that much schooling, many doctors are looking to put down roots and start a family, he said.

B.C. requires additional training because Kuckreja was trained in internal medicine, which requires a three-year residency in the U.S. and a four-year residency in Canada.

“I trained in the U.S. I’m board-certified in internal medicine in the U.S. I have no blemishes on my record,” said Kuckreja. “It should be a lot easier for us to come back without jumping through all these hoops.”

When he returned home to Victoria last summer, he was surprised to hear so many people complain they didn’t have a family doctor. It’s estimated one million people in B.C. don’t have a family doctor, including about 100,000 on the south Island.

“Everybody you talk to in Victoria says the same thing,” said Kuckreja. “And at the same time when I tried to apply for my medical license, I was told: ‘You have to do another year of training,’ which made me frustrated, so I’m really happy the province is taking this seriously.”

Aly Husein, who also did his undergrad in B.C. and attended medical school in the Caribbean, similarly tried unsuccessfully to return to B.C. For Husein, the news of coming changes for internationally educated graduates was bittersweet.

“I signed in the U.S. for three years before all this was mentioned,” he said via email. “A lot of us have.”

Although the changes announced Sunday are promising, he added, prohibitive fees remain. “The fees are still in the thousands to apply and get back.”