Rebecca Warburton worked as everything from a CIA analyst contributing to then-U.S. president Jimmy Carter’s daily briefings to a researcher and University of Victoria professor, but it was the infamous 2012 Health Ministry firings that put her in the headlines.

Health Minister Adrian Dix, who advocated on behalf of the fired researchers at first in Opposition and later in government, said the general advice in such controversies is to move on, but that wasn’t Warburton’s style.

“She was absolutely a force of nature,” Dix said of Warburton, who died suddenly at age 70 on March 13 after complications involving a ruptured appendix.

“This was a remarkable, determined, generous person who stuck to her position and stuck to her belief in the evidence.”

Warburton, who earned a master’s degree in economics at the London School of Economics, worked for several B.C. government ministries, and won a tenure-track position in UVic’s School of Public Administration three years after earning her PhD through the University of London in 1996.

She was at the top of her game when she and seven of her colleagues, including her husband, were swept up in a flawed investigation by the then-B.C. Liberal government. The probe involved an alleged data privacy breach and contract-award irregularities related to the B.C. Health Ministry’s pharmaceutical services division. All of them were fired.

“It was a case of people starting with conclusions and trying to fashion evidence to support those conclusions,” Dix said.

Conflict-of-interest and irregular-contract claims and a web of other accusations arose from Warburton’s relationship to her husband, Bill Warburton, an economist who had a contract with the Provincial Health Services Authority, and his distant cousin Malcolm Maclure, a Health Ministry epidemiologist with whom she shared a role as co-director in the ministry’s pharmaceutical branch.

Whistleblower Alana James, a Health Ministry employee, claimed that a rogue group of researchers was bypassing protocols and sharing anonymized data. But over the years, the investigation unravelled.

Within months, UVic PhD student Roderick MacIsaac, who was working as a co-op student with the Health Ministry, had killed himself. Media scrutiny intensified and there was growing concern about stalled research.

Some fired Health Ministry researchers were reviewing off-label use of antipsychotics in children and seniors. MacIsaac and another researcher were reviewing B.C.’s anti-smoking program and smoking-cessation drugs, including Champix, which was the subject of a warning from Health Canada about adverse psychiatric side effects.

Health Ministry data use was suspended for UVic, which was studying Alzheimer’s medication, as well as for the Therapeutics Initiative — a group of researchers based at the University of British Columbia who independently assess the effectiveness of medications to provide a balance to drug industry-sponsored information sources.

It was eventually revealed there was no RCMP investigation, as the B.C. Liberal government had publicly stated.

The facts were straightforward but the process wasn’t, “so that was a long fight,” Dix said.

Bill Warburton said Rebecca and the rest of the group believed strongly in drug safety and effectiveness, and worked hard to ensure money wasn’t wasted on ineffective drugs.

“So she felt really betrayed when the firings happened and puzzled they would do this with no evidence,” said Bill Warburton, adding that, as MacIsaac’s professor, she was deeply affected by his death.

Dix said Rebecca Warburton was of a generation who believed in the evidence and tried to apply it, sometimes against powerful forces. That belief sustained her through the health firings, he said.

All of the fired researchers eventually won their wrongful-dismissal suits. A sweeping investigation into the firings, led by B.C.’s ombudsperson Jay Chalke, resulted in a 488-page report called Misfire, released in 2017, that found the eight researchers were wrongly fired by the Health Ministry.

The report resulted in the researchers being exonerated. Forty-one recommendations were implemented under the subsequent NDP government, including a government apology, changes to the way allegations are investigated, cash payments to the fired researchers and a UVic scholarship for PhD students in honour of MacIsaac.

Rebecca Warburton returned full-time to the University of Victoria, taking a stronger interest in the rights and protections of faculty members and university governance, UVic’s school of public administration said in an online tribute after her death.

She took on several more roles, and, though she retired as an associate professor in 2020, she continued to serve in the senate — a term that would have ended on June 30.

The couple had reflected recently on their favourite published papers and, for both, it was one they wrote together: “Canada Needs Better Data for Evidenced-Based Policy,” published in 2004, “a paper that benefited from her relentless logic and attention to detail and my ranting and raving,” Bill Warburton said.

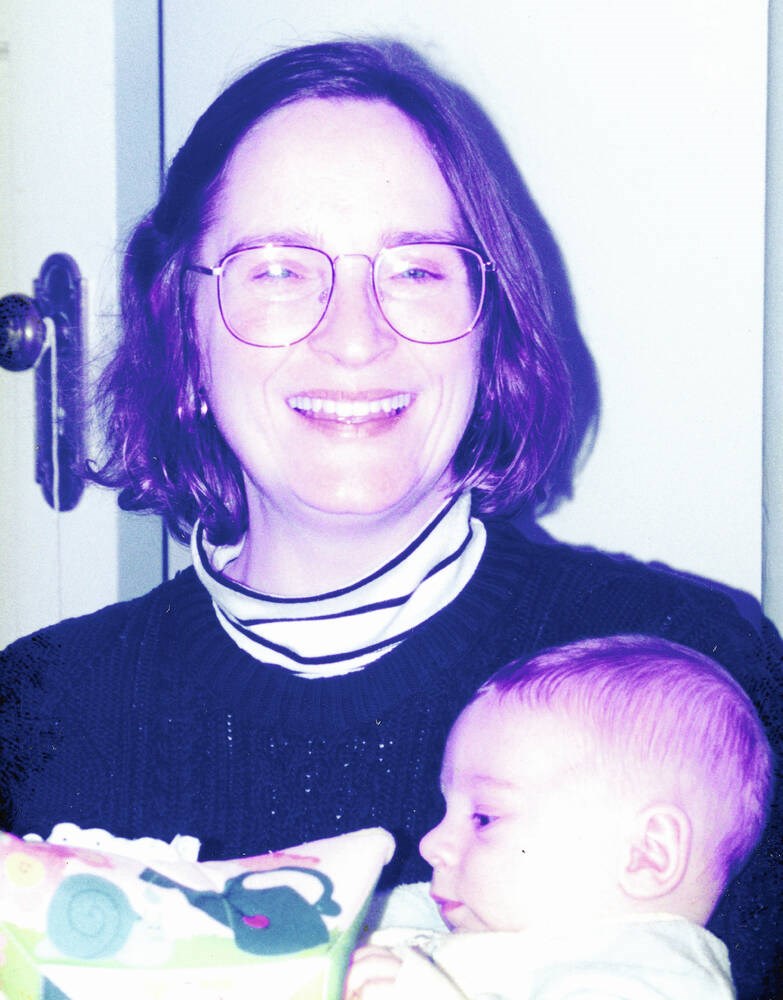

The two moved to Victoria in 1982 after falling in love with the city during a trip from Sandspit in Haida Gwaii, where they lived briefly. Their only son, Dave, arrived in 1991.

“Everybody else thinks of her as feisty but my son Dave and I think of her as kind and loving,” Bill Warburton said. She made fresh fruit salad every morning and baked quiche, he said. “She really looked after us.”

She took up snowboarding at 46 and wakeboarding in her 50s.

The stress of the investigation and subsequent pandemic affected her fitness, but, in recent years, the couple, who were married for 43 years, delighted in walking their son’s husky-shepherd cross Finn — taking him to a dog park, where Rebecca also made many friends “the way she does.”

“Things were pretty good,” he said.

Rebecca Warburton’s ashes will be scattered in her favourite place, Lake Cowichan, this summer. A celebration of life was held on April 27.

>>> To comment on this article, write a letter to the editor: [email protected]