The COVID-19 lockdown has prompted schools and libraries to give the public free online access to many books, and Canadian publishers are warning that the model cuts sharply into their revenue and cannot be sustained.

The news is especially dire for B.C.’s community of 30 publishers, the largest in Canada outside of Ontario. Publishing houses say local publishers are among the only channels for B.C. authors to develop, and if either publishers or authors cannot get paid for their work, B.C.’s literary ecosystem may be in danger.

“Publishers are smart and resilient, but there’s a limit,” said Ruth Linka, associate publisher with Victoria-based . “It’s really hard to say right now how long publishers can continue with really drastic cuts to their income.

“Like any business, you can’t pay rent or your staff and keep publishing books if you don’t have revenue coming in. I don’t think we are talking about days or weeks … but for sure, if something doesn’t improve over the next couple of months, it’s not going to be sustainable for many in our industry.”

Executive Director Kate Edwards said the book industry was already under pressure, mostly with the advent of e-books and other formats. As the costs skyrocket with the move to different online formats, the core revenue of publishers and authors, which is generated from book sales, has remained flat as the price of books remains largely unchanged.

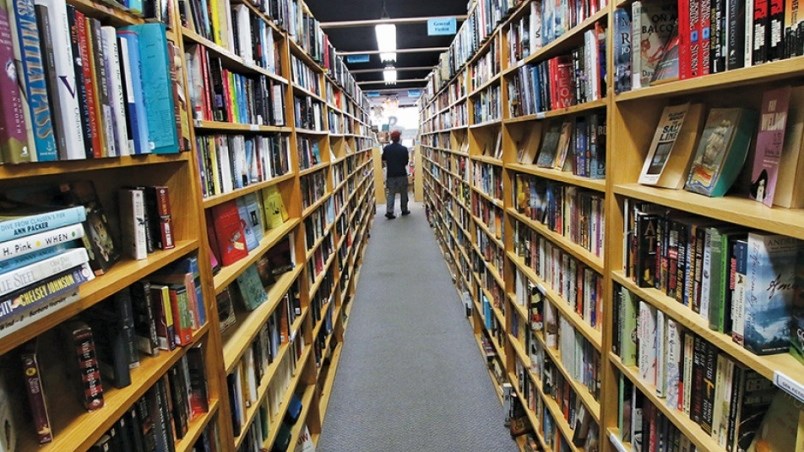

Now, with the pandemic essentially shutting down bookstores for months (with some finally reopening this month under B.C.’s Phase 2 relaunch), that lifeline for the industry has essentially been slowed to a trickle, Edwards said.

The most recent data indicates book sales so far this year have fallen 30% from 2019 figures, with sales at retail book stores plummeting 60%.

Worse, another major channel of book sales, to schools and libraries, has also been turned upside down with social distancing. Publishers are now issuing free temporary licences that allow students to download books or teachers to read the books to students over the internet.

“As schools quickly had to change the way they teach – which is from a distance – publishers began quickly receiving requests for digital versions of books,” Edwards said. “The teacher may have the books in the classroom, and that’s not available to students … in the short-term. Given the emergency, publishers have been as flexible and generous as possible to ensure students’ education is not disrupted.”

But these free licences cannot be issued for long-term use because it would push publishers out of business – taking many homegrown authors in B.C. and other provinces with them, Edwards noted.

“As we look forward to next school year … publishers can supply [books] in various formats through whatever channels are available to ensure that the content is not only available, but compensated for on the other side.”

The Canadian publishing industry annually generates about $1.6 billion. It includes everything from trades (fiction and non-fiction) and children’s books to educational and scholarly text. The largest international houses are the most resilient to economic challenges like COVID-19 because the likes of Penguin Random House and HarperCollins control the market for books from most of the world’s high-profile authors, and those are the books most in demand.

In comparison, the Canadian-owned publishing houses, which represent about $425 million in annual sales – are largely small-to-medium-sized companies that concentrate on newer Canadian authors, an indispensable part of the grassroots literary culture of Canada.

“Local publishers are responsible for about 80% of new Canadian books published each year,” Edwards said. “And British Columbia is one of the strongest regional publishing cultures in the country. Publishers are finding new authors in the local community and investing in their careers … and they are competing with the entire world of content.”

She added that, even with retail stores now reopening, most of the books being sold are already in stock; publishers have not received many new orders and may have to accept returned unsold stock given the COVID-19 lockdown.

For Orca Books, a publisher mainly of children’s books with a 35-year history and a staff of 30, the task of publishing 80 to 100 books a year as it normally does has become herculean, even for an industry that has survived multiple challenges in recent years, Linka said.

“This is completely unprecedented. For sure there have been times when the economy was suffering … even libraries and schools have had budget cuts before. But to have all this happen at once to this extent, it’s unfathomable just three months ago. I heard from a lot of publishers that there has been a 70% to 80% decrease in sales, and some of it has been mitigated by e-book sales, but it hasn’t come close to replacing what we had.”

Both Edwards and Linka said all the stakeholders in the educational sector need to sit down and discuss fair pay for content starting in the fall school year.

Publishers say they are open to suggestions, but the bottom line is that every revenue channel helps in keeping businesses open and authors and publishing houses need to get compensated if their work is read – especially when the overall market has been squeezed.

If not, Linka said, the threat of a B.C. reading and education culture dominated by content from outside the province becomes inescapable, and that would hurt the literature world and erode B.C.’s unique cultural identity.

“Publishing started in Western Canada decades ago when people in the West felt their stories weren’t being represented,” Linka said. “Â鶹´«Ã½Ó³»has fantastic urban, diverse content … and vibrant publishers like Anvil Publishing and Arsenal Pulp Press who tell these stories around the world.

“Every region of the world should have their own publishing industry so their voices are represented.… We love it when we can represent a broader social experience, and local publishing enables that because it’s more in touch with the landscape, history, culture and, ultimately, people of our region.

Read more from