Since 2007, the former military base 35 km southwest of Prince George has been home to Baldy Hughes Therapeutic Community (BHTC) operated by the B.C. New Hope Recovery Society. The society leased the land in “as is” condition before premier Gordon Campbell’s Liberal government bought it.

Men living at BHCT to this day receive intensive addictions counseling, health and fitness instruction, vocational and agricultural instruction and leadership skills lessons. Some consider BHTC a last-chance rehab for hardcore addicts to get healthy.

However, studies of the land they live on for a year indicate the presence of leaded paint, asbestos and other carcinogens and even uranium or mercury presence dating back to the Cold War. The information comes from documents obtained by Glacier Media under access to information laws.

And B.C. Ministry of Environment records show no major remediation work has been done on the land where addicts live, work and grow food.

Further, a 1988 Department of National Defence (DND) land decommissioning study contained a Health and Welfare Canada warning to guard site workers’ health around dangers from asbestos, removal of which remains ongoing.

“The board of directors and I were aware of and retained a copy of the DND environmental assessment before we leased the property,” said Lorne Mayencourt, a former BC Liberal MLA. He cofounded BHTC with �鶹��ýӳ��real estate developer and society chair Kevin England. They scoured B.C. for a site.

“It was the only place we were welcome,” said Mayencourt, who raised $200,000 to open BHTC. “We leased it. We wanted to lock the price in for the property so we had a lease price and a purchase price.”

Some material removal has been done and some buildings have been demolished.

“We discovered asbestos floor tile underneath carpeting in our TV room,” Mayencourt said. “We immediately asked WorkSafeBC for direction and were told it needed to be removed by a professional remediation team and we did so at considerable cost to the society.”

Not quite, said recovering addict Mark Harris. He’s 11 years drug-free, something he credits to Baldy Hughes. He was there before the provincial purchase and said patients in protective suits removed asbestos building tiles during renovations under expert supervision.

“Regular maintenance and large renovations of the facilities at Baldy Hughes have occurred,” England said in a statement to Glacier Media. “The renovations have been done to suit the needs of the therapeutic community and farm as well as abatement work to remove hazardous material. Baldy Hughes is a safe place for the employees to work and for the residents to live, develop work skills and recover.”

Based on Italian model

Mayencourt established BHTC for holistic treatment of addicts modeled on a centre he visited in San Patrignano, Italy. The idea is to help addicts to regain emotional, physical, emotional and spiritual well-being through a program combining clinical therapy and health care support with work.

“Another large piece is providing educational opportunities to our residents such as the B.C. certificate of graduation,” England said.

But, stressed, Mayencourt, “BHTC is not a health care facility. Clients accessed primary health care in Prince George.”

Dr. Sherry Mumford, who oversaw addiction treatment for the Fraser Health Authority for 15 years, disagreed.

“Physical, emotional, psychological, it’s all health,” she said.

Treatment costs $3,000 a month but government assistance is available.

“Baldy Hughes receives its funding from partner subsidies and tenancy fees paid by various ministries for some residents,” England said. “Another group of residents pay privately for their accommodation and treatment.”

Military Base

BHTC uses infrastructure laid down when U.S. Air Force opened a radar base in 1954, part of the North American Aerospace Defense Command system against Soviet Union air and missile attacks. DND took over in 1963, closing the base in 1987. That closure involved an environmental study, which estimated a price tag of $2.4 million for environmental cleanup and remediation costs – $4.7 million in 2021 funds.

Cleanup for re-use would cost less, it said.

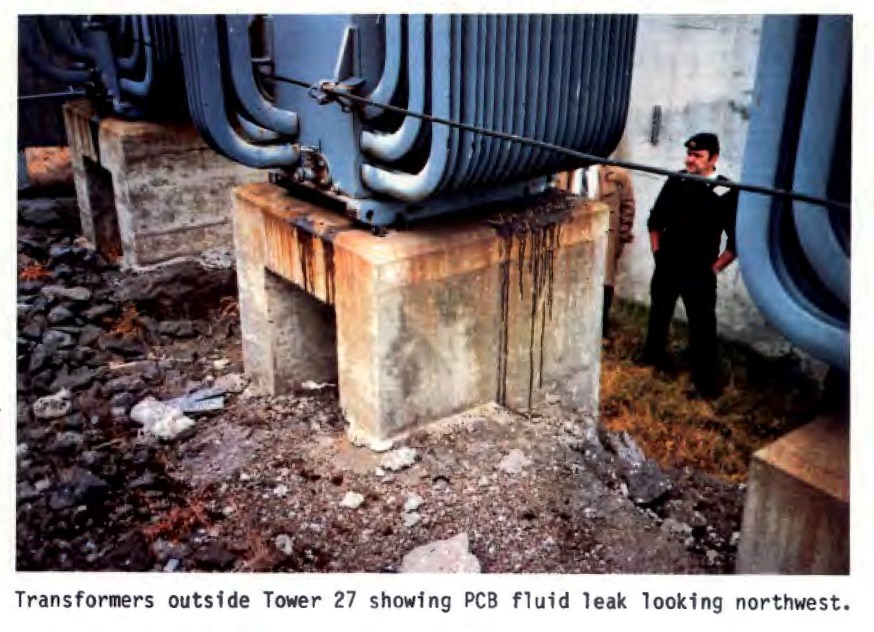

The study found significant soil contamination from carcinogenic polychlorinated biphenyl (PCBs) from transformers and capacitors; ground contamination from crankcase oil; radiation from the radar facility; and asbestos pipe insulation, floor tiles and siding.

WorkSafeBC has long identified asbestos exposure as a cancer risk.

A Canadian Forces member looks at a transformer leaking potentially carcinogenic PCBs at CFB Baldy Hughes, now a B.C.-owned addiction treatment centre. Associated Engineering photo, Department of National Defence

A Canadian Forces member looks at a transformer leaking potentially carcinogenic PCBs at CFB Baldy Hughes, now a B.C.-owned addiction treatment centre. Associated Engineering photo, Department of National Defence

Septic tank overflow testing found, “elevated levels of hydrocarbons, cadmium, copper, mercury, lead, and zinc.” Low levels of PCBs were found in the soil.

While transformers and radioactive radar tubes were removed, documents said fluids from contaminated transformers may have been filtered through oil possibly used for dust suppression on unpaved base roads.

EF, who sought anonymity due to fear of reprisals and future job losses, worked at BHTC a decade ago. He said roads remained unpaved and dusty.

The report said the minimum work for site re-use would involve cleaning up a PCB spill, demolishing one building and removing contaminated soil beneath it, removing a septic tank and cleaning up overflow, and cleaning an oil-contaminated area.

Under a re-use scenario, the report said, “it is assumed that DND would be responsible for the clean up and restoration of potentially hazardous materials and areas of suspected or known contamination.”

Indeed, when Circle “J” Ranch Society bought the property from Public Works Canada in 1988, one condition gave Ottawa the two-year right “to perform any environmental clean-up that may result from consultant studies.”

That responsibility sits with Environment Canada, which has not responded to Glacier Media 2019 requests for information.

Several ownership changes ended with Edmonton-based Prowler Leasing winning the .

Three years later, the Provincial Rental Housing Corp. (PRHC, administered by BC Housing) paid $2.85 million for the land. From that, $175,000 was deducted as an “environmental remediation purchase credit,” heavily redacted BC Housing documents show.

However, BC Assessment put the 2010 assessed value at $648,000.

The purchase funds approval came from B.C.’s all-Liberal MLA Treasury Board including cabinet ministers Colin Hansen, Shirley Bond and Rich Coleman.

by

So why did PRHC make the purchase?“It was a successful program and it was the only one they had,” Mayencourt said. “It was taking a lot of people off the street. They came to us because they wanted us to keep operating it.”

The deal also cleared up the society’s $131,164 rent arrears.

Asbestos, lead, carcinogens, mercury, radioactive chips

However, even after the provincial purchase, the site remains contaminated, with people still living and working there.

A 2012 BC Housing hazardous materials inventory indicated asbestos in floors, ceilings, walls and pipe insulation; high levels of lead-containing paints throughout; ozone-depleting chlorofluorocarbons (CFCs) in kitchen and other areas; possible PCBs in light fixtures, potential mercury in thermostats, potentially radioactive chips in smoke detectors.

Alone or in various combinations, those materials were present throughout accommodations, workshops, garages, administration and recreation buildings, washrooms, laundry and music rooms. A 2018 inventory notes some material removal but much remains.

EF spent much time in one of the asbestos-tainted areas.

“None of this was shared with me,” he said when shown the inventories. “I would have been out of there a lot quicker.”

And, said Mayencourt, by October 2008, “all of the buildings in use had been remediated to the best of our ability.”

But, any cleanup is far from complete. Materials such as asbestos, mercury, lead, radioactive chips and PCBs remained, the 2018 inventory found, noting issues in the administration building, dormitories, community centre, laundry and music rooms.

by

Moreover, those reports followed three performed as due diligence for Victoria’s purchase. That trio of studies found contamination including uranium in groundwater. “The source of the uranium was underdetermined but may be naturally occurring,” one report said.

Those reports cost BC Housing $92,198. With them came a projected $327,000 cleanup cost.

“The location of the contamination is not within the proximity of the residents and therefore does not cause any direct or immediate life and safety hazards,” a November 24, 2010, memo said.

But, as late as October 2019, a BC Housing project request for proposals identified asbestos and lead paint as issues for abatement. It also outlined building and fire code problems.

“Over the last 10 years, we have spent approximately $180,000 on these kinds of jobs,” BC Housing said January 29. “We want Baldy Hughes to be a safe place for the residents to live, work and recover.”

That figure is 4% of the millions DND estimated for cleanup and much of the expense was in a contract given to a Liberal Party donor.

The figure can also be contrasted with the $175,000 deducted from the December 2010 purchase price for environmental cleanup. It remains half of the March 2010 $327,900 remediation plan’s estimated price tag and far from DND’s estimated millions.

@jhainswo

BC Housing Hazmat Records 30 15119 Records(1) by Emma Crawford Hampel, BIV.com on Scribd

.jpeg;w=120;h=80;mode=crop)