There’s no finish line in sight for Jessica Michalofsky.

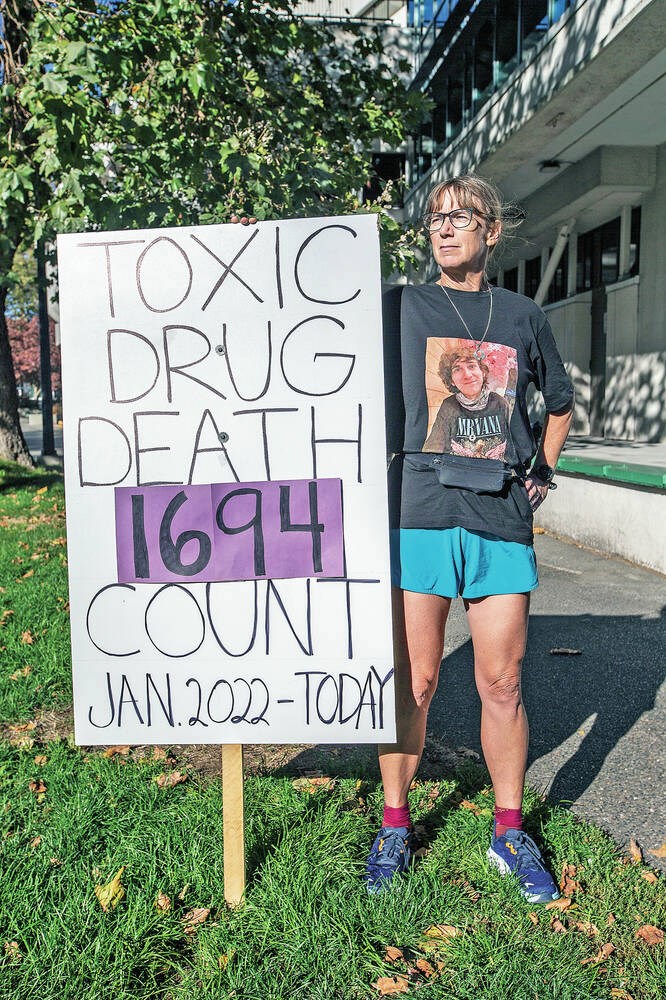

Since last week, the Ironman athlete has been running her own private marathon every day around the Ministry of Health building on Blanshard Street to bring attention to the ongoing opioid crisis and the need for improved access to safe drug supply.

On Aug. 30, she lost her only son, Aubrey, to a toxic overdose of methamphetamine and fentanyl. Aubrey would have celebrated his 26th birthday on Sept. 5. Instead, Michalofsky got a call from one of his friends about his death.

“I’ve thought about the moment of his dying so many times. I knew it was likely and yet, he was so successful and I was so hopeful for him,” she said Tuesday afternoon, taking a break from one of the 70 laps that make up her hours-long daily 42.2-kilometre marathon.

The last time Michalofsky talked to Aubrey, he congratulated her on completing the Penticton Ironman on Aug. 28. She told him she’d pick him up two days later at his home in Winlaw in the West Kootenays.

But when she arrived, she couldn’t reach him. His friends thought he was sleeping and didn’t administer naloxone. “He was going to be so good. We were going to go shopping because it was his birthday. I knew he was struggling, but he’d struggled before. I thought: ‘I’ll just go get him and it will be all right.’ But I just missed him by hours. It just seems so cruel.”

Aubrey, who attended Oak Bay High School and Vic High, started experimenting with drugs at age 16 or 17. Worried he would die, Michalofsky moved him to the Kootenays because she thought it was safer.

“He did really well there for a while. He went back to school and got into a law and justice program at Selkirk College, where he received two awards,” Michalofsky said. “He was kind of a rising star.”

But he was also struggling. Aubrey didn’t like the side-effects of methadone and had trouble showing up every day and making appointments. The nearest pharmacy was 50 kilometres away in Nelson and he didn’t have a car. When COVID hit, he couldn’t hitchhike. “He went off methadone in July and I knew things were not good,” said Michalofksy, 51, who teaches English at Camosun College.

People honk their horns when they see Michalofksy running or notice her poster of the grim overdose death toll on the boulevard outside the ministry. Since Jan. 1, 1,694 people have died in B.C. from illicit drug overdoses.

Workers from Cool Aid, their naloxone kits hanging from their waists, walked over to thank her.

“Can I give you a high five? Are you the runner?” said a young outreach worker with tears in his eyes.

“I’m just doing what I can. I’ll be here tomorrow,” said Michalofsky, who plans to keep running as long as she can.

She wants more from the Ministry of Health and Ministry for Mental Health and Addictions. Despite her daily marathons, she said no one has come out of the building to talk to her.

“We have to start providing safe supply. We have to start offering heroin, fentanyl, cocaine and meth,” said Michalofsky. “No one has a chance in this toxic black-market drug environment. First-time users, recreational users, long-term drug users are all using the same drugs. We need more education. I don’t think the public understands safe supply.”

Michalofsky said she sent an email to Mental Health and Addictions Minister Sheila Malcolmson but had not received a reply.

In an interview Wednesday, Malcolmson said she was “certainly planning to respond” to Michalofsky.

“I have heard through media that she would like to meet with me and I really welcome that. She didn’t request that in her email to me, but I benefit greatly from talking directly to family and friends of people who lost their lives to the poisoned drug supply and I would really welcome an opportunity to learn from her,” she said.

B.C. is the only place in Canada where people can be prescribed safe supply, said Malcolmson. Thousands of people have accessed safe supply since the program started in March 2020. More substances and more access points were added in the summer of 2021.

“We continue to do that work and we are very grateful to the doctors and nurse practitioners who are working through health authorities and community clinics to provide safe supply and we are working every day to remove barriers in getting more prescribers coming into the program,” said the minister.

Safe supply would have saved Aubrey’s life, Michalofsky believes.

“I’m sure if someone had said: ‘Here’s the safe supply’ he would have said; ‘Absolutely because my mum’s coming and I have school.’ ”