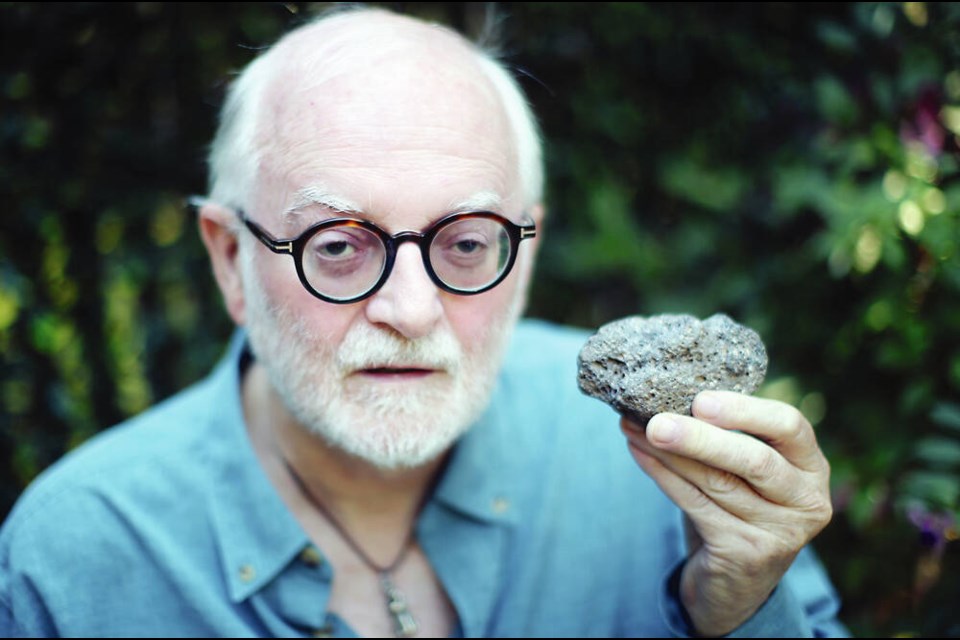

The origins of a carved sandstone pillar once heralded as an Indigenous artifact by the Royal B.C. Museum is a mystery that might never be solved, says the museum’s former curator of archeology.

Grant Keddie said he was surprised and saddened to hear that the museum had returned the stone to a local carver before it had been properly analyzed.

“It’s just too bad when you can’t follow through on something,” said Keddie, who retired on Jan. 31 after 50 years as a curator.

He continues to believe the pillar could be an actual Indigenous ceremonial stone figure that fell from the eroding Dallas Road cliffs onto the beach below, where it was discovered decades later by a local artist who carved a face on it.

“It’s very likely the original stone didn’t have a face,” said Keddie. “It was just a plain rock that had been shaped in a round fashion and stuck in the ground.”

Controversy erupted last year when the museum announced it had discovered a ritual pillar used in Lekwungen salmon and puberty ceremonies. A few days later, carver Ray Boudreau saw a photo of the stone pillar and said he had carved it. He sent photos to the media of a strikingly similar sculpture he had worked on three years earlier.

Embarrassed, the museum said the provenance of the pillar would be reviewed with museum staff, local First Nations and the carver.

Keddie was instructed not to talk to the media. The silence created a lot of speculation.

Then on Sept. 13, the museum returned the stone to Boudreau with an apology.

“I would like to express my gratitude for your patience as we navigated this unfamiliar territory and extend sincere apologies for the errors made during the process,” wrote Alicia Dubois, the museum’s chief executive officer. “I assure you that as a team, we have learned from this experience and are taking concrete measures to ensure similar errors are not made in future.”

It’s unfortunate the museum did not do the needed work on the stone, said Keddie. In an article he is preparing for his website, the archeologist explains why he still believes the stone was likely an Indigenous ritual figure.

The 100-kilogram oblong stone pillar was discovered on the beach between Finlayson and Cloverdale points, below Beacon Hill Park. Keddie and a team of four wrestled the heavy stone off the beach.

It was taken to the museum and placed in successive batches of fresh water to leach out the salt. When the conservation work was completed, the museum invited members of the Songhees and Esquimalt First Nations to have a private viewing of the stone.

Finlayson Point was once a defensive village site of the Lekwungen people and burial cairns are still there at the top of Beacon Hill, said Keddie. The oral history of the Lekwungen people from the 1880 described special stones not far from Finlayson Point.

The stones were used to influence the wind and were also where a girl “reaching the age of puberty must take some salmon to a number of large stones.” Special stones were also found in Cadboro Bay.

Keddie’s article also contains images of stone figures with similar bulbous faces from B.C.’s south coast.

“I was all excited,” said Keddie. “It’s very rare you have an oral tradition of something happening in the distant past and actually find the evidence for it. That’s a really exciting thing.”

At the time of the discovery, most of the museum staff, including Keddie, were working at home because of COVID. Keddie did not have the chance to look at the stone properly once it was cleaned and do a more thorough examination by magnification. He had also hoped to do tests to determine the source of the sandstone, which is not natural to the area.

Keddie did not want to go public about the find, but said he was “under pressure to make a news story.”

And when Boudreau came forward, Keddie continued to investigate the provenance of the stone, going to the beach to look at some of Boudreau’s other carvings.

“There was absolutely no question that was his carving,” he concluded.

Keddie noted that in media interviews, Boudreau said he knew the stone was “unusual” and “already shaped.”

“I would still like to lend to the idea that it could have actually been in the hands of First Nations people at one time because it was too perfect,” the carver told the Times Colonist.

During this time, all the managers at the museum left for different reasons. Keddie was disappointed to suddenly see the stone given to Boudreau.

“I realized all the new management knew nothing of the history. Who made the decision to return it? I don’t have a clue. The point is the corporate knowledge is gone and that becomes a real problem. We can’t be certain whether or not this is an actual Indigenous stone.”

Keddie still believes, based on the evidence at the time, that he made the right decision.

“Now I know that there’s a more complex story that is still not over, a mystery that goes on forever,” he said.

Ray Boudreau thinks Keddie’s theory is a stretch — but he isn’t sure.

“Definitely, it was blank when I found it,” he said. “Pretty hard to prove, but who knows? Could have been. I can’t argue with what happened before I found it.”

The stone pillar is still lying on his front lawn. Boudeau hasn’t done anything with it and said he’s hesitant to dive right in and get carving.

“It’s got its own little character. I look at it every single day. I’m a little leery about carving it. You got to wonder about spiritual powers too,” he said. “To be sort of a rectangular square shape is not something nature puts out. This was totally square, really odd. I’ll give you that.”

Despite requests for more information, the museum has not provided an explanation of what happened.

>>> To comment on this article, write a letter to the editor: [email protected]

.JPG;w=120;h=80;mode=crop)