The Nuchatlaht First Nation on Â鶹´«Ã½Ó³»Island’s west coast has won a landmark legal case asserting Aboriginal title to part of its traditional territory on Nootka Island.

The ruling marks the first time a B.C. trial court has recognized a First Nation’s Aboriginal title, the nation said in a statement.

A previous land-title decision in favour of the Tsilhqot’in First Nation in central B.C. was won in the Supreme Court of Canada after an appeal.

“We are celebrating this victory and looking ahead for the future of our nation. There is still much that needs to be done to restore our land and heal our people,” said Tyee Ha’wiih Chief Jordan Michael.

The nation said it plans to practise Nuu-chah-nulth stewardship of the land, about 11 square kilometres, based on the principle of Hishuk-ish tsa’walk, meaning everything is connected.

Owen Stewart, a lawyer who represented the nation, called the ruling a “first of its kind” that made the Nuchatlaht nation the second-largest Aboriginal title holder in B.C.

The decision gives the nation the authority to decide what to do with the land and benefit economically from its use, he said. The land’s value has been estimated at between $28 million and $280 million.

“These are life-changing numbers potentially for the community,” he said.

The ruling sets a precedent that says Aboriginal title exists in B.C. “and it’s worth going after,” Stewart said.

More than 80 per cent of old-growth forests have been cleared in the region and no watersheds are intact, the nation said. Its aim is to rehabilitate the ecosystem, including strengthening wild salmon populations, while supporting its people and culture.

“This is a real chance at becoming self-sustaining. For far too long we’ve been isolated on this tiny little reserve watching all our resources getting stripped away, while not taking any real part in the economic development of our nation,” Nuchatlaht Coun. Erick Michael said.

The nation first brought the claim in 2017. That led to a 54-day trial that started in March 2022.

Last May, the court rejected the nation’s claim to about 200 square kilometres of Crown land covering a portion of Nootka Island and much of the surrounding coastline, but acknowledged Nuchatlaht have Aboriginal title somewhere on Nootka Island.

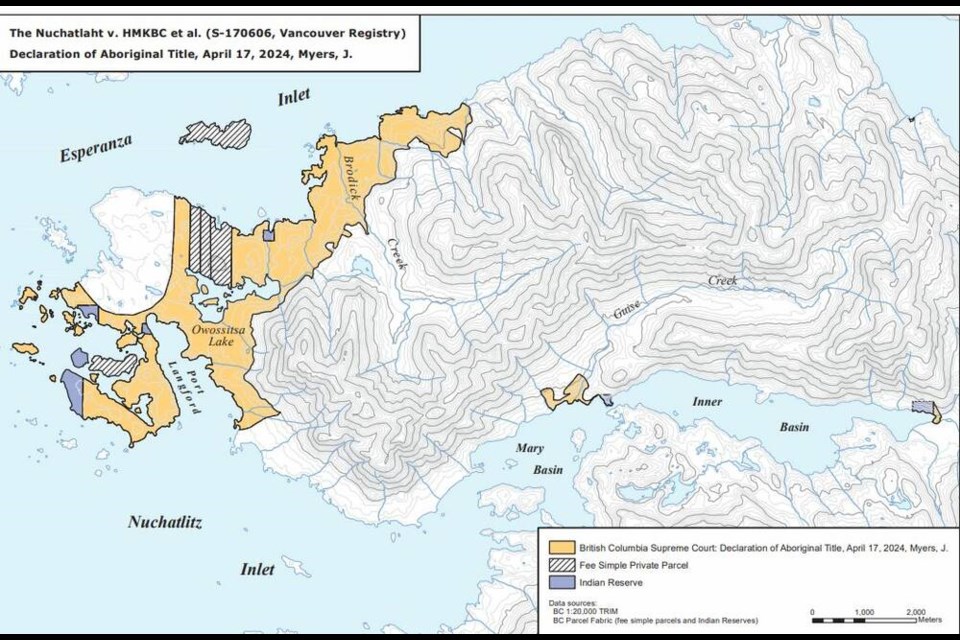

The decision rendered last week identifies those areas where the court determined the nation has Aboriginal title as the northwest corner of the claim area.

The nation is considering appealing the decision to assert title to the remainder of the original claim area.

“We’re not just fighting for Nuchatlaht. We want to show the world that we can manage better, we can enhance better, and there will be enough for everybody,” said Archie Little, a Nuchatlaht elder and councillor.

The nation’s traditional territory covers the northern half of Nootka Island and nearby inlets.

During the trial, the court heard that the Nuchatlaht moved to a village on Nootka Island in the 1780s and that they occupied the area in 1846, when the Crown resolved boundary disputes with the United States and claimed sovereignty over what is now B.C.

However, the province denied that the Nuchatlaht occupied all of the territory it was claiming.

In the lawsuit filed in 2017, the nation argued that the B.C. and federal governments denied Nuchatlaht rights by authorizing logging and “effectively dispossessing” the nation of territory.

The ruling will likely have ripple effects for other nations interested in asserting Aboriginal title to their land, said Torrance Coste, associate director for the Wilderness Committee, one of many organizations that has been supporting the nation since the beginning of the case.

“If the court can rule with the Nuchatlaht, then that title should be recognized and should extend to other nations,” he said.

Coste said it’s clear all the land in the nation’s original claim belongs to the Nuchatlaht and he hopes that will be recognized, either through an appeal or by the province admitting it.

The Wilderness Committee and other groups that form the Friends of Nuchatlaht point to a discrepancy between the provincial government’s claim that it is committed to reconciliation and respect for Indigenous rights and arguing in court against the Nuchatlaht’s claim to its traditional territory.

“And if they say they care about reconciliation, to recognize that that comes with land rights too,” Coste said.