Picture a minority government – one riding high on popularity while navigating the pandemic – calling a snap election as the official Opposition leader attempts to make an impression on the electorate.

This, despite opposition parties’ reluctance to blow up the legislature and go to the polls with voters seemingly wary of the prospect of an election amid rising COVID-19 cases.

Last year, those circumstances resulted in the BC NDP converting its minority government into a solid majority. It also delivered record-low voter turnout, with only 54.5% casting their ballots.

This morning (Aug. 15), Governor General Mary Simon approved Prime Minister Justin Trudeau's request to dissolve Parliament, triggering a federal election to be held Sept. 20. With this vote ahead, could the nation as a whole be facing a similar lack of engagement?

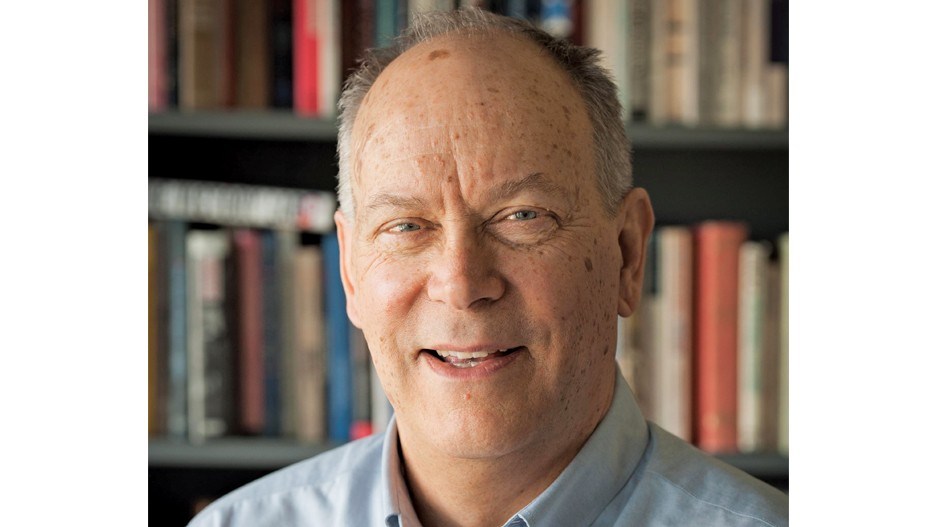

“In general, there is no enthusiasm for having an election. The government can’t really give a reason in substance for calling one,” said Richard Johnston, professor emeritus of political science at the University of British Columbia.

“It’s probably going to be a lower-turnout election than the last one.”

Voter turnout for the 2019 federal election was 67%, down 1.3 percentage points from the previous 2015 election.

Sanjay Jeram, a senior lecturer of political science at Simon Fraser University, said it’s hard to predict where voter turnout will land in the next election.

If there are no significant events that galvanize the country, he said the next election is unlikely to hit 2015’s 68.3% turnout. Instead, it could land somewhere in the low 60s.

Uncertainty brought on by the pandemic’s fourth wave and the Delta variant could also play a part in whether people cast a ballot, according to Jeram.

“Some people … will still feel uncomfortable going out to vote, and a lot of people who are even given alternative options won’t exercise them,” he said.

A record number of British Columbians – 720,000 – requested mail-in ballots in the 2020 provincial election.

Jeram said it shows that alternative options could help with voter turnout down the road, but adoption might be slow if the electorate prefers the traditional methods of casting a ballot.

There are also some notable distinctions this year on the federal front compared with where B.C. stood during last year’s provincial election.

The economy is more stable and a mass vaccination campaign has loosened restrictions on gatherings.

While car rallies and social media may have been the go-to for electioneers last fall, door-knockers and in-person events have the potential to energize voters, according to Johnston.

“Part of what may happen is that the parties will experiment early and see how it goes. And so we might see some degree of learning about how actually they conduct the campaign side of the election,” he said. “But at the end of the day, it’s quite important for parties to appear on the doorstep and to enable their supporters to get to the polls or enable their supporters to cast the ballot by whatever means it is.”

However, Johnston warned of the potential for the federal Liberals’ early election call to backfire.

There have been 17 snap elections throughout the federal and provincial levels across Canada since 1958. Prior to that, the last snap election was called in 1917.

Of those, the results have been pretty much split, with the governing party losing eight times and winning nine times.

“Anything you say about 2021 has to be qualified by the fact that we’re still in a pandemic,” Johnston said, referring to the success of previous snap election calls.