Backcountry recreationalists might like to imagine that only select activities disturb local grizzly bears, but the truth is, every sport can impact coexistence.

That was one of the messages from Dr. Lana Ciarniello, one of four speakers who took part in a webinar called Coexistence Recreation and Grizzly Bears in the Backcountry, hosted by AWARE and the Coast to Cascades Grizzly Bear Initiative on Jan. 11.

“What’s interesting is there was a survey done and recreationalists, they actually blame other recreationalists that do other recreation for having an effect on bears, but their recreation doesn’t necessarily,” she said. “That’s not true. All recreation poses a risk to wildlife. Why? Through actual displacement moving them off the land.”

Ciarniello—who is the co-chair of the International Union for the Conservation of Nature’s bear specialist’s group’s human-bear conflict expert team—broke down recreation into high speed and low speed. High-speed included mountain biking, during which a rider is focused on moving down a track at a high speed, often quietly.

“If you have ever taken a bear awareness course in your life, you will know that these are the exact things we tell you not to do,” she said. “We want you to make noise, to be aware of your surroundings or consider your surroundings. And why is this? Because all of these high-speed activities limit the reaction time the bears have to respond to us.”

A study conducted in Yellowstone National Park, for example, put collars on bears and GPS receivers on recreationalists and found that bears do in fact move out of the direct path of noisy, slow-moving people.

To that end, uphill bikers have been found to have no greater chance of getting into a conflict with a bear than a hiker who’s making noise, Ciarniello added.

But even hikers have been found to impact grizzlies. During COVID-19, for example, more people have been hitting the trails—and at earlier and later times when bears are likely to be out—and spacing out. (That’s not to mention ear-bud-wearing hikers that can’t hear their surroundings, or those with off-leash dogs, which increases the risk of human-bear conflicts.)

“Bears like predictability,” she said. “They want us to be predictable and they can try to move around us. They’re trying to coexist with us. When we remove that predictability from the equation, it gets even more stressful and displacement gets even higher.”

While winter recreationalists might think they’re off the hook for disturbing hibernating bears, that’s not actually true. All noisy, motorized recreational vehicles also have an impact.

“It’s winter, the bear is denning up in the alpine, a snowmobile comes up. It’s very loud and noisy. Now where is that bear going to flee to? Because it’s in the middle of winter. It’s not eating, it’s not urinating, it’s not defecating and it needs every little bit of energy and fat it has to maintain it through that wintertime … So these noisy, recreational activities have these big displacement impacts on them,” Ciarniello said.

For her part, during the webinar, Melanie Percy, the protected areas applied ecologist for BC Parks, fielded questions about how other agencies handle grizzly bear-human interactions in their jurisdictions.

“Grizzly bears are an indicator of ecosystem health and more and more agencies are realizing that if we focus on the management of the landscape and on managing people and human use, these proactive management strategies lessen the need for hands-on bear management,” Percy said. “That’s where most agencies are going to these days.”

The first strategy is mindful planning of facilities like trails, campgrounds, and picnic areas. That includes not putting facilities in known wildlife movement corridors.

“Some … agencies are actually relocating facilities that either have historically been in places we now realize are bad or even newer ones,” she said. “I have heard of some trails that have been removed because they were leading people into conflict with bears.”

Another approach some agencies are taking is to manage attractants—including unnatural attractants like human food. That includes things like bear lockers or ensuring berry bushes are cut back from campgrounds.

Then there are methods like signage and area closures during certain times of the year.

In other locations, bear spray is mandatory for hikers (it should be noted the panel agreed bear spray is the only deterrent you need to carry in the backcountry; bangers and bells don’t work) or mandating that hikers hike in groups of minimum four people.

“That’s a very common one for national parks for grizzly access restrictions,” Percy added. “These restrictions come with pretty hefty fines too under the National Parks Act regulations. You can be fined up to $25,000 for failing to comply.”

Some agencies conduct more traditional bear management, too, including electric fencing around campgrounds or bear hazing. Educating the public about bear safety is also often a component.

For anyone who opposes closures to protect bears, it’s important to remember, “we have a choice as to whether we go out into the backcountry or not,” Percy said. “We have lots of other places to go. Bears don’t. They don’t have a choice. They need to be there.”

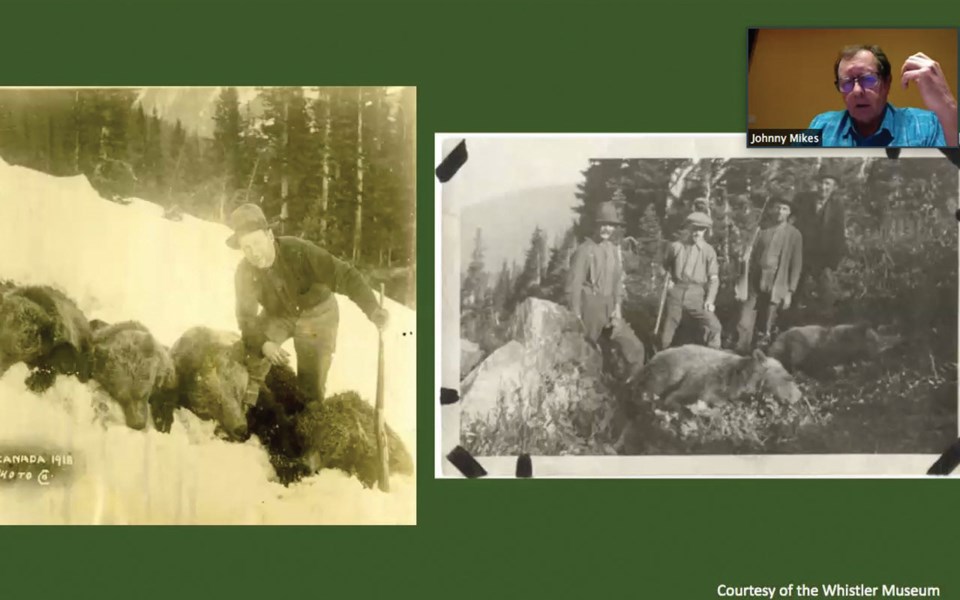

More than 330 people logged in to the virtual event, said Claire Ruddy, executive director of AWARE. As part of the event, Chief Ian Campbell of the Squamish Nation shared information and stories about the importance of grizzly bears to the Nation, Squamish ecosystem biologist, Steve Rochetta, also talked about his research on the local population, and Johnny Mikes, field coordinator with Coast to Cascades Grizzly Bear Initiative shared more about his group and numbers of grizzlies in the area.

For Ruddy, the importance of a healthy grizzly bear population is clear. “What we see when we have healthy groups of population on the landscape is that we have clean water, clean air, space for wildlife to roam and those things are what many other species of wildlife need, too,” she said. “When we do things that are good for grizzlies, we’re not just doing it for that one species, we’re doing it for many.”

You can watch the now.