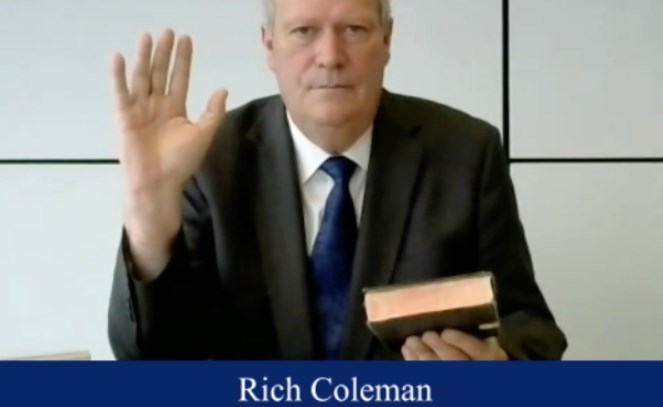

On the last day of testimony for the Commission of Inquiry into Money Laundering in B.C., former B.C. deputy premier Rich Coleman walked back some comments he made to Commissioner Austin Cullen last month, while two senior Mounties denied any notion the career politician interfered in casino investigations.

Coleman was called back to the stand to clarify what exactly he did when a January 2011 CBC News story exposed, again, alleged money laundering in casinos he was overseeing at the time.

CBC had published an RCMP-authorized interview with inspector Barry Baxter on January 4, 2011, in which Baxter outlined serious and evidence-based concerns of drug cash being washed through casinos.

However, at the time, Coleman dismissed Baxter’s claims to media, saying, “I don't agree with him and neither do all the superiors of his in the RCMP. And that's why I said to them, OK, guys, we're going to look at this.”

But on April 28, Coleman told Cullen he did not speak to RCMP after the story broke.

Counsel Brock Martland called Coleman back to clarify the relationship Coleman had with the RCMP. This relationship could be relevant in explaining why Coleman cancelled a gambling enforcement team (IGET) in 2009 and oversaw the disbandment of another casino-related unit (IPOC) in 2012.

Martland asked Coleman if he considered his 2011 media comments tantamount to “downplaying” the matter.

Coleman denied such a notion. He went on to explain that he did not speak directly to senior Mounties, but rather he had his director of police services, Kevin Begg, find out with the RCMP what was going on, as Baxter’s comments surprised him.

“I should have used the word ‘we’ instead of ‘I,’” explained Coleman, adding he was “caught off guard by the comments, not the issue.”

Coleman said at the time he didn’t deem the cash suspicious, as it could have been legitimate. Coleman also openly questioned the media reports and again affirmed government casino regulations were of high standards.

But Martland circled back, saying, “Do you agree this amounts to downplaying or undermining those who were critical or concerned about there being a money-laundering problem in casinos?”

Coleman again disagreed, although he did acknowledge in hindsight, “It may have been unfair to Mr.Baxter.”

Coleman’s BC Liberal government and/or the B.C. Lottery Corp. have faced allegations of wilful blindness or ignorance of the law in order to pad government coffers. Over a decade, officials courted wealthy overseas gamblers, raising bet limits from $500 to $100,000.

Two senior Mounties in charge of the RCMP in B.C. at the time corroborated Coleman’s new testimony. Deputy commissioner for Canada West Gary Bass and deputy commissioner for B.C. Craig Callens both said Coleman never spoke to them after the CBC story.

Bass and Callens acknowledged Baxter had been authorized to speak but said it was unusual.

Baxter previously told the commission he received an “unusual” and cryptic call after the story published from Callens, who told him to “know your audience.”

Callens explained his version in an affidavit, stating, “I said words to the effect of: some might perceive you’re trying to embarrass the government into doing something. That is not my way of doing things, and not how the RCMP handles these things in British Columbia.” He added, “I have no recollection of Mr. Begg making any comments about Mr. Coleman.”

Baxter had only wanted to inform the public of the growing criminal elements inside casinos, the commission has heard. But the RCMP walked away from such investigations between 2012 and 2015. Callens explained in his affidavit he had “many balls in the air.”

The ability for transnational organized crime to allegedly launder between $100 million and $200 million of drug cash annually turned out to be a significant factor in Vancouver’s deadly opioid overdose public health emergency.

The inquiry did not address specifics of how crime networks began operating in casinos and how they are alleged to have spilled over into the housing market.

The inquiry looked at money laundering risks in real estate from policy perspectives and is expected to draft recommendations around matters such as beneficial ownership structures, corporate transparency, and mortgage fraud prevention.

The inquiry’s scope was provincial, so it did not delve into federal banking regulations, which oversee the bulk of money-laundering rules. The inquiry did, however, expose holes in federal financial reporting requirements.

Cullen will hear final submissions in July and send a final report to the Attorney General’s office by the end of the year.