Warning: This story may be distressing to readers.

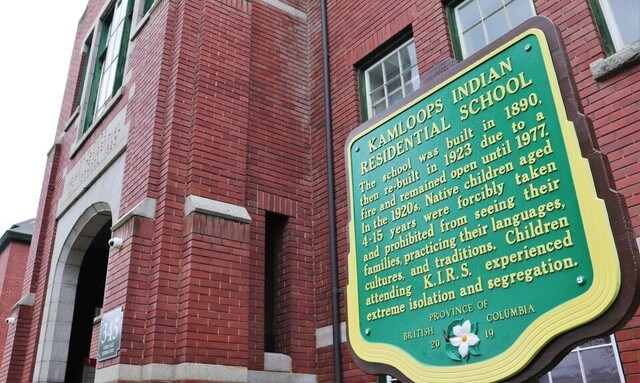

The school dump at the former Kamloops Indian Residential School should be searched for children's bodies, Tk'emlúps te Secwépemc (TteS) said July 22.

“We have had survivors say probably our next step should be the old dump site at the residential school and the old stories of children being thrown in the dump,” says Ted Gottfriedson, the language and cultural department manager at TteS.

Gottfriedson made the revelation during a webinar Thursday morning, hosted by Tk'emlúps te Secwépemc. The webinar saw archaeologists discuss the techniques being used for the continuing research into the 215 children’s graves found at the former residential school site.

“Everything we’re doing is for those 215 kids,” he says. “It’s 215-plus. It’s not done.”

The archaeologists explained how ground-penetrating radar (GPR) could be assisted with other technology to identify grave sites.

The work would be done in cooperation and consultation with local communities and survivors. It would also recognize culturally appropriate practices.

And survivors’ knowledge will be part of that work, TteS Chief Rosanne Casimir says.

“We see you. We love you and we believe you,” she says, noting children at the school came from all over B.C. as well as Yukon, Alberta and the United States.

Casimir says the Canadian Archaeological Association (CAA) and the Institute of Prairie and Indigenous Archaeology (IPIA) are providing expertise for the search, which involves both aerial and ground searching.

“This is a long process that will take significant time and resources,”Casimir says. “They were children robbed of their childhoods and families. ... We now need to give them the dignity they never had.”

The provincial government will provide $475,000 to each of B.C.’s 18 Indian residential school sites and three hospitals for work to investigate and exhume graves at those sites, Minister of Indigenous Relations and Reconciliation Murray Rankin said July 20.

On May 27, Casimir announced 215 graves had been located on the grounds of the school with the use of GPR.

Earlier this month, the Penelakut Tribe said about 160 undocumented and unmarked graves have been found at the site of the Kuper Island Indian Residential School.

And, the Ê”aq’am Indigenous group of the Ktunaxa First Nation announced in late June the finding of 182 graves near Cranbrook. Other Indigenous groups such as Williams Lake First Nation are also doing ground-penetrating radar work.

CAA president Dr. Lisa Hodgetts says each community doing searches needs to undertake its “long and difficult journey” at its own pace.

First in that work, she says, is recognizing the emotional impact the work will have. Then comes taking guidance from communities, honouring the importance of ceremony, collecting oral histories and Indigenous knowledge, clarifying expectations and providing results as soon as possible to reduce emotional impacts of waiting.

“Memorialization can take place at any stage in the process,” Hodgetts says.

Also of importance are past records held by communities, the National Truth and Reconciliation Commission, governments and churches.

“We echo the calls for organizations that haven’t released those records to do so immediately,” she says.

UBC archaeologist Dr. Andrew Martindale says GPR gives reflections of what is in the ground to depths of about two metres. Those reflections can be visualized and interpreted, he says.

IPIA director Kisha Supernant, a University of Alberta anthropology professor, says aerial observations using planes or drones can assist the ground-based work.

For immediate assistance to those who may need it, the National Indian Residential School Crisis Line is available 24 hours a day at 1-866-925-4419.