ST. JOHN'S, N.L. — Erica Humber-Shears says there are deep anxieties within her western Newfoundland community, as residents — most of whom work in the fishing sector — wait for an end to a six-week impasse in the province's crab fishery.

The days of mounting fear and unease in Humber Arm South, N.L., feel like 1992, when the federal government ended the province's cod fishery after stocks had collapsed, said Humber-Shears, the town's mayor.

"I was a teenager during that time, but it's just that eerie kind of feeling. It's an eerie silence," she said. "People are really starting to fret over, 'Where am I going to go to find work? How am I going to feed my family? How am I going to pay my mortgage?'"

Crab fishers in Newfoundland and Labrador are refusing to fish after prices were set in early April at $2.20 a pound, a sharp drop from last year's opening price of $7.60 a pound. The fishers say it's not enough to make a living, and so far they haven't budged.

Prices are set by a panel that hears arguments from the fishers' union and the group representing fish processors. The Association of Seafood Producers has also dug in its heels, saying it will not offer anything more than $2.20 a pound to start with, but that it would increase the price at agreed-upon intervals if the crab market improves.

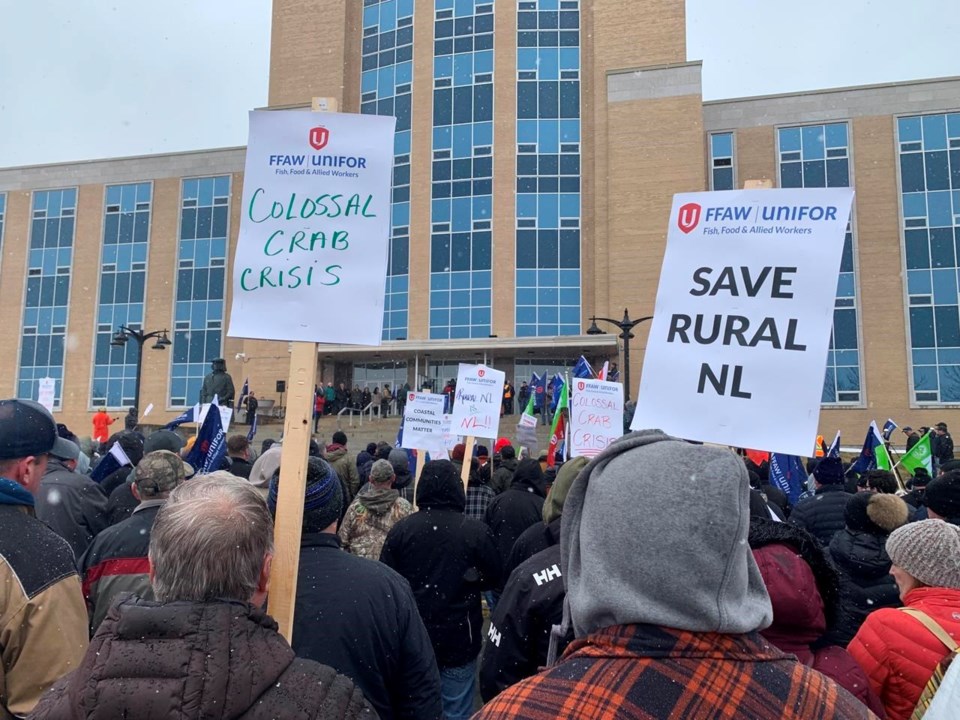

The Fish, Food and Allied Workers Union has asked that the provincial government allow its members to fish for crab and sell their catch outside the province, noting that fishers in Nova Scotia and New Brunswick are earning $2.25 a pound at the wharf. Greg Pretty, the union's president, said Wednesday even being able to sell elsewhere for an extra nickel a pound "would change a lot" because it would create competition. But he said the government rejected the union's request.

Humber Arm South has a population of about 1,500 people and it's home to many harvesters, as well as a fish plant that has been the main source of employment in the area for over 100 years. Without any crab coming in, they're all out of work.

The plant processes other species including lobster and herring. But crab is the longest season, and it's typically the species that gives the plant's workers — more than 300 at peak times — the minimum hours they need to qualify for unemployment insurance, which gets them through the winter, Humber-Shears said.Â

"We have families, two and three people in a family, that are employed in that industry. So, potentially, a whole household will have no income," she said.

In St. Mary's, a town of about 315 people on the other side of Newfoundland, the local fish plant was set to open this year for the first time in about eight years after a new owner overhauled it, said Steve Ryan, the town's mayor.

"Here before, you'd never see a house for sale. Houses were just left barred up," Ryan said. "Now they're not only for sale, they've all been sold. People want to move here now."

He said the reopening of the fish plant was supposed to be a success story for St. Mary's and for rural Newfoundland, which has long struggled with a dwindling, aging population as young people moved away for work. But the crab fishery standoff has cast a "dark cloud" over all that, and left people worried about their future, he said.

More than 100 local people should be working at the plant right now, as well as about 80 temporary foreign workers from Mexico, who arrived over a week ago, he said. They're living in housing provided by the plant, and some residents have been inviting them for meals, but they're also in limbo and they just want to work, Ryan said.

He, too, was a teenager during the cod moratorium, which ultimately put more than 30,000 Newfoundlanders and Labradorians out of work. Like Humber-Shears, he said the fear and uncertainty now in St. Mary's has the same feeling.

"This is the closest thing to the moratorium as we can have," he said. "This is it again, right now."

This report by The Canadian Press was first published May 18, 2023.

Sarah Smellie, The Canadian Press