Exposure to increased levels of carbon dioxide in the atmosphere accelerates the reproductive cycle of mountain pine beetles, a new study has found.

The , published in the journal Global Change Biology, show the beetle’s typical 40-day brooding period accelerated to 30 days when they were exposed to higher levels of carbon dioxide (CO2), the driving force behind human-caused climate change.

Rashaduz Zaman, lead author and a PhD candidate in forest biology and management at the University of Alberta, said the results show that as the climate changes, insects like the mountain pine beetle are adapting at a time trees are becoming more vulnerable to things like drought.

“The prediction is the beetle can bounce back and attack more,” Zaman said.

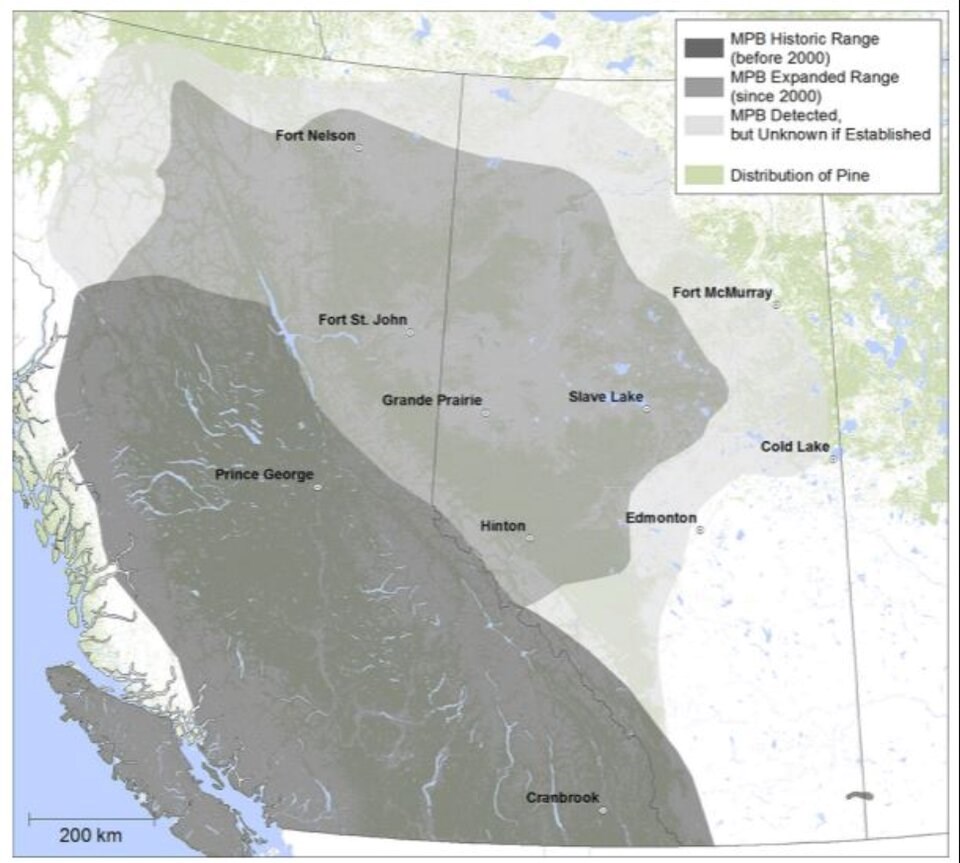

Since the early 1990s, the mountain pine beetle has attacked about 18 million hectares of forest, including half of the total volume of commercial lodgepole pine in British Columbia, according to Natural Resources Canada.

Warmer winters and drier summers allowed the beetle to extend well beyond its traditional range in the boreal forests of B.C. But it remained unclear how the beetle will be affected by climate change and the rising concentrations of ozone and carbon dioxide that come with it.

Beetles learned to adapt in a simulated future climate

Climate change has pushed CO2 concentrations past 421 parts per million, substantially higher than the pre-industrial level of 280 parts per million, and less than half the 1,000 parts per million that could be achieved at some point this century.

To simulate those conditions, the University of Alberta researchers introduced male and female pairs into freshly cut lodgepole pine logs, which were placed in a controlled climate chamber.

Next, they manipulated the environment by changing levels of CO2, ozone and relative humidity between 33 per cent and 66 per cent. The researchers also introduced three species of fungus that have a symbiotic relationship with the beetles. After a month or so, the logs were returned to ambient conditions to allow the beetles' broods to emerge.

​The researchers found the lower the humidity, the more the fungi grew and the more the beetles reproduced. High CO2 concentrations were also found to speed up the growth of larvae.

But when it came to ozone — another gas whose atmospheric concentration is expected to rise over the coming decades — increased concentrations were initially found to have a negative impact on mountain pine beetle reproduction and brood fitness. ​

​In the wild, a mountain pine beetle will attack a tree by making a hole in it. Once inside, it releases pheromones to attract other beetles, while releasing fungi that blocks a tree's own toxic defences and inhibits arboreal mechanisms for transporting water and nutrients.

In the lab, the spike in ozone gas was originally found to degrade the pheromones beetles rely on for finding a mate. At first, it seemed the gas may have evened the odds and pushed back against the effects of CO2. But over the next three to four months, the following beetle generations started to adapt.

“When we tested the ozone, the first generation that came out, they were smaller and lower weight. By the third generation, they developed resistance,” said Zaman.

Expect more outbreaks

The results could have significant results for places like British Columbia, where mountain pine beetle infestations have already wiped out millions of hectares of forest in recent decades.

Zaman said climate modelling suggests more drought in B.C.’s future, something expected to weaken pine trees and make them more susceptible to infestation.

He said years of above-average wildfire may have helped halt the beetle's advance, but over the long-term, Zaman and his colleagues forecast the mountain pine beetle will be able to adapt to a new forest regime and once again cause “significant ecological and economic consequences.”

“B.C. has been a hot spot for the pine beetle,” Zaman said. “We expect more outbreaks.”

If there’s any good news, the scientist said more studies still need to be done to confirm what they found.